Virginia Hall was known by many names during her career. Working as a spy for Britain’s Special Operations Executive during the Second World War, she was known as Marie, Nicolas, Diane, Germaine, and Artemis.

To the German Gestapo, though, she was more than just an alias – she was the person they considered to be the most dangerous Allied spy of them all.

While hunting snipe in Turkey, she accidentally shot herself in the left foot at point-blank range with a 12 gauge shotgun.

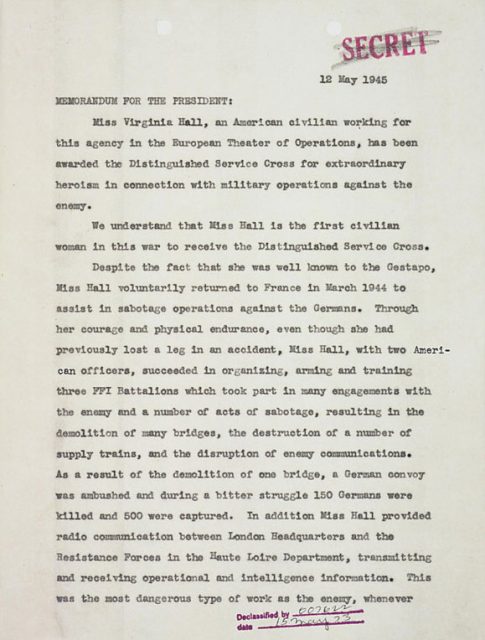

By the end of the war, the team of spies and resistance agents she led had destroyed a number of bridges, derailed German freight trains, killed at least 150 German troops and agents, and had captured around 500 Germans. Amazingly enough, she did all of this with only one fully functional leg.

After the war she was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, making her the only female civilian to be awarded one during WWII.

Born in 1906 in Baltimore, Maryland, Virginia Hall showed great promise from an early age. She excelled at her studies and displayed a particular talent for languages.

By the time she graduated from Barnard College, she was fluent in French, German, and Italian – languages that would be perfect for the wartime espionage in which she would eventually become involved.

Her path to success was not without setbacks, though. Just as she was taking her first steps into what looked like it was going to be a long and distinguished diplomatic career in the American Foreign Service, disaster struck. While hunting snipe in Turkey, she accidentally shot herself in the left foot at point-blank range with a 12 gauge shotgun.

Her left leg had to be amputated below the knee, and this disability effectively put an end to any hopes the 27-year-old Hall had of continuing her career in the Foreign Service.

Formerly posted to the US embassy in Warsaw, she contacted the embassy in Vienna in the hopes of gaining employment there but was told in no uncertain terms that, due to her disability, her career as a diplomat was over.

This could have been the end of the line for Hall, but then something of great significance happened — an event that was to change the course of her life and that of millions of others too: the Second World War broke out.

Hall immediately joined the Ambulance Corps in France, but after much of France fell to the seemingly unstoppable German advance, she made her way across the Channel. Once there, she volunteered for Britain’s Special Operations Executive (SOE), a newly formed organization specializing in espionage and covert operations.

The men at the SOE looked past Hall’s injured leg and saw great potential in the fact that she was fluent in three of the most useful languages for their purposes. The SOE signed her on, gave her intensive training in weapons use, covert communication, and the art of disguise, along with other essential skills for a spy.

Shortly after her training, she was back in France, posing as an American reporter, to take on the Germans.

From 1941 to 1942, she worked tirelessly in France, assisting the French Resistance, coordinating operations, gathering intelligence, running safehouses, and smuggling people out of the country — all while passing on important information to her SOE superiors in Britain.

She established her own network of agents called HECKLER, whose activities and missions she coordinated with great success from sabotaging German communication lines to smuggling downed British airmen out of the country.

German counterintelligence inevitably learned about HECKLER and were soon offering generous bounties for the capture of the “Lady with the Limp” or simply the “Limping Lady” as they called her. The Gestapo went as far as to say that she was the most dangerous of all the Allied spies and the one they most wanted to get their hands on.

Despite all the precautions Hall had taken, the Gestapo net soon began to tighten around her and her operatives. Realizing that capture was imminent as the rest of France fell to the Germans in late 1942, Hall decided to make a daring escape across the Pyrenees on foot in the dead of winter.

She did not tell her guide about her prosthetic leg, which she had nicknamed “Cuthbert.” The journey took her over mountain passes 7,500 feet in altitude, and sometimes she had to cover as much as 50 miles in two days, which was incredibly painful with her prosthetic leg.

When she was able to send a message to the SOE in Britain, they asked how the journey was going. She mentioned that Cuthbert had been giving her trouble, to which they replied that she should simply “eliminate” him, not realizing who — or, rather, what — Cuthbert really was.

Hall managed to reach Spain safely, but once there she was arrested at a train station and charged with having entered the country illegally.

After a stay of six weeks in a Spanish prison, she was able to contact American officials in Barcelona who managed to secure her release. She continued to work for the SOE from Madrid.

In 1943, she was made a Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) – a great honor, especially for a non-British citizen.

After this, Hall joined the American Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the United States’ wartime intelligence agency, and requested that she be allowed to return to France to continue fighting the Germans there.

She was smuggled back into the country and assumed the disguise of a rural peasant woman, a task for which she dyed her hair gray, shuffled like an old lady, and even had her teeth fillings altered to match the style of French dentistry.

Under this new identity, she assisted with coordinating supply drops for Resistance troops and then Allied troops who were advancing through France after the D-Day landings.

She also reported on German troop movements and sabotaged German supply lines and communications, tasks which she and her team performed flawlessly. In September 1944, the OSS decided that she had done enough, and she was pulled out of France.

For the role she played in the Allied war effort, she was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, and was the only female civilian to receive this decoration in WWII.

President Truman wished to present her with the award personally in a public ceremony, but Hall politely refused this request as she did not want her identity to be known.

Read another story from us: Eileen Nearne, a British WW2 Heroine & Sort of Female James Bond

After the war, she worked for the CIA until 1966 when she retired. She lived out the rest of her days in peace and passed away at the age of 76 in 1982.

Virginia Hall, the “Lady with the Limp,” will long be remembered as one of the greatest American spies of the Second World War.