In 1954, the French decided to draw their struggles in what was once called French Indochina to a close. From then until the end of the Vietnam war, it was the United States of America that would be the primary Western power seeking to solidify their strength in the region and oppose the further spread of communism.

But it wouldn’t be until almost ten years later that direct conflict between U.S. Regular forces and those of North Vietnam would engage and begin an all-out war.

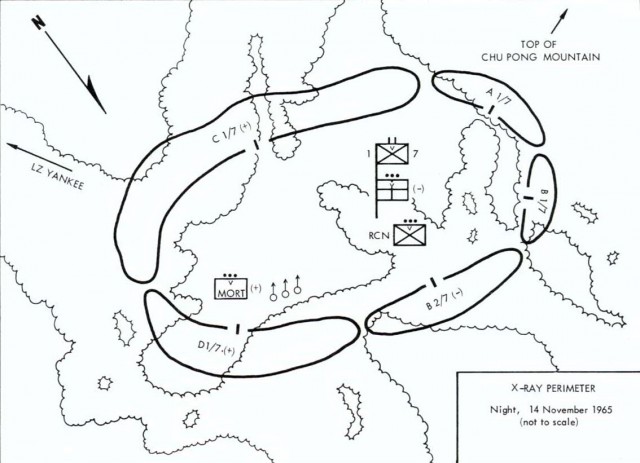

The day this began was November 14, 1965, in the Ia Drang Valley of the Central Highlands of Vietnam. American troops were transported by helicopter to clear landing zones and set up the command center of the operation at a large termite mound in Landing Zone X-Ray (LZ X-Ray).

The LZs were about 30 minutes round trip from the base, and the 16 Huey helicopters could only transport about 12 men each at once. The first boots hit the ground at 10:48 and by 12:15, shots were being fired. It would be many hours before the battalions were at full strength and the battle would last for several days.

For the first two of those days, it was the job of the 1st and 2nd battalions of the 7th Air Cavalry to hold LZ X-Ray against some 2,500 North Vietnamese and Viet Cong troops. Much of the fabled history of this battle revolves around that 1st Battalion and its commander, Lieutenant Colonel Hal Moore.

The U.S. troops defeated a much larger enemy force, but with very heavy loses.

1 The Battle of Ia Drang was the first major engagement between U.S. and North Vietnamese regulars.

To many, this marks the beginning of the U.S.’s Vietnam War in the days of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s ordered troop build-up. Much of the force Lieutenant Colonel Moore was leading into the jungle had never been combat tested. The North Vietnamese, however, both knew the dense terrain and had been fighting Western nations in it since the beginning of the French Indochina war in 1945.

This battle would soon teach both sides about how to fight the rest of the war.

2 Ia Drang also served as a test for the U.S. military of its new air mobility tactics.

The location of the battle, far into the jungle from any roads, meant troops had to be airlifted in. The idea was that whole battalions could be dropped and complete their mission on the ground, calling in artillery barrages, helicopter support, and bombing sorties (including napalm) as needed, guided by coordinates given from the battalions’ radio operators.

For this purpose, the Air Cavalry was born.

3 This battle was also a learning opportunity for the North Vietnamese military.

Upon getting an idea of the U.S. air mobility tactics, Colonel Nguyễn Hữu An is quoted as saying “Move inside the column, grab them by the belt, and thus avoid casualties from the artillery and air.”

He knew he had to get his troops as close as possible to his enemy, to mix into their lines if they were to avoid direct bombardments.

4 One main tactic Colonel An began using to achieve his counter-strategy to the U.S. air mobility was the human wave.

During the nights of the battle especially, large groups of North Vietnamese would attempt to sneak as far up as possible and then charge the U.S. lines.

This tactic would be seen in Vietnam, again and again, including in the Tet Offensive.

5 One defining element of Ia Drang was the separation and attempted rescues of Lieutenant Henry Herrick’s platoon.

The first shots of the battle were fired at 12:15 on Bravo Company and, as the platoons advanced, Herrick’s was soon flanked and cut off. Before long, eight men were dead and 13 wounded, including Herrick.

The platoon was so pinned down they couldn’t even dig foxholes. Command passed to Sargent Ernie Savage who called in multiple air strikes around the platoon’s position. These and the strong stand made by the remaining men pinned down on the knoll, lead to the death of scores of North Vietnamese troops, who never managed to wipe out the platoon.

Two attempts were made to rescue Herrick’s platoon that day, but both failed. They remained pinned down through the night until around 3:30 the next afternoon when a third rescue attempt succeeded.

6 In the second push to rescue Herrick’s platoon, Lieutenant Walter Marm earned the Medal of Honor for his actions.

As Alpha and Bravo company advanced to the lost platoon’s position, Marm’s platoon came under fire from an entrenched enemy machine gun. Marm assaulted the gun himself, with rifle and grenades. He was wounded in the neck and jaw in his lone charge but killed all the combatants at the machine gun. The next day, twelve North Vietnamese soldiers were found dead in the nest.

He was wounded in the neck and jaw in his lone charge but killed all the combatants at the machine gun. The next day, twelve North Vietnamese soldiers were found dead in the nest.

7 For stopping a North Vietnamese advance on the second day, Specialist William Parish earned the Silver Star.

In the early morning attacks of the second day, Charlie Company was taking fire from advances on three sides of their position.

Parish, positioned on Delta Company’s lines, suppressed one advance, using all his M-60 and .45 ammunition. More than 100 enemy troops were found dead around his foxhole after the battle.

8 When the North Vietnamese broke through U.S. lines early in the morning on day two, Lieutenant Charlie W. Hastings called in code “Broken Arrow.”

This was done on Moore’s orders and signaled that the unit was being overrun and that all air support available was to be sent in. This brought in an intense barrage on the enemy, but also lead to a severe friendly fire incident.

As two F-100 Super Sabre jets swooped in to deliver their napalm payload, Hastings saw that they were headed dangerously close to the U.S. line. He tried to call them off, but one jet didn’t hear the frantic plea in time. Several U.S. soldiers were wounded and killed in the horrific accident.

9 Moore had the same command as Colonel Custer.

The Air Cavalry was a new advent, with the development of air mobility tactics. Moore was appointed to command the newly named 7th Air Cavalry (well, the 1st Battalion thereof, at least).

Custer had led the 7th Cavalry during the American Indian wars and died, along with all his men at his famed last stand. This parallel didn’t escape Moore, who must have been all to aware of the history of Little Big Horn when his battalion and the 2nd were surrounded on all sides by a much larger and native force.

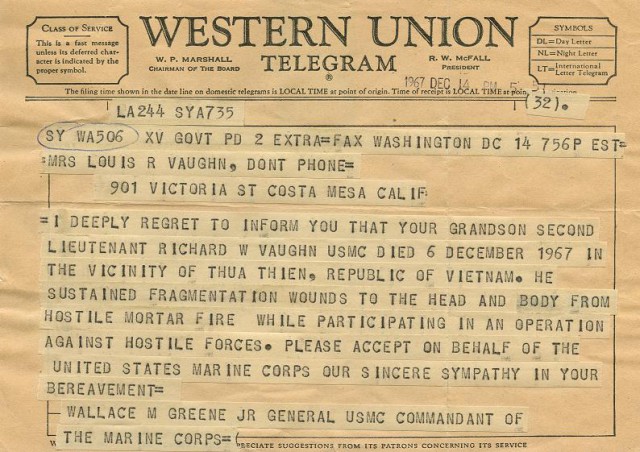

10 As U.S. soldiers fell during the battle, the comfort of their grieving families was handled by Moore’s wife.

The U.S. military was not yet prepared to deliver news of dead soldiers. Telegrams were thus dispatched via taxi cab driver to families, informing them of their loss. Upon noticing this, Julia Compton Moore took it upon herself to go by the houses of those under her husband’s command and console the grieving widows and children.

Only after Mrs. Moore complained about this to the Army did they set up teams of one officer and one chaplain to deliver the heartbreaking letters from then onward.

In 1992, Moore and reporter Joseph L. Galloway (who was present at the battle) published the book We Were Soldiers Once…And Young about the battle. The 2002 film We Were Soldiers brought this story to the screen.