Iceland is a beautiful and unique country situated in the North Atlantic somewhere between the British Isles and Greenland. The island is riddled with glaciers, active volcanoes, rugged mountains, and hot pools. It is Europe’s most sparsely populated country, and that was no different in the 1940s.

But when we think of the Second World War, Iceland is probably the last country that comes to mind. However, some might point out that the island had a strategically important location in the North Atlantic, making it perfect for maritime control of the area.

The Germans very soon recognized the tactical importance of Iceland, as did their British foes. All maritime conveys to Murmansk in Russia were forced to pass close to Iceland. Also, the air route between Europe and the United States was via the small island nation.

Naturally, the Nazis soon had a plan to invade. They called it “Operation Ikarus.” However, it was not the Third Reich that would ultimately impinge upon Icelandic sovereignty and neutrality but the British, in an unsanctioned act that rattled the Icelanders for many years.

Some historians say that the British had no choice but to invade Iceland

After the occupation of Denmark and Norway in “Operation Weserübung” or “Weser Exercise” in April 1940, the German naval position in relation to England and France in the North Sea had improved considerably.

As a result, the German High Command, along with their counterparts in the Navy, worked out a plan of invasion for Iceland.

The in-depth study examined how to wrest control of air and sea bases on the island. They wanted to gain control of the English and French sea trade routes and so cut off the two countries from the outside world by a naval and aerial blockade.

Erich Raeder was the Commander-in-Chief of the Kriegsmarine (navy). When France had been defeated in the Western campaign on June 20, 1940, he presented Adolf Hitler with the results of the study, as well as the continuing preparations for a military landing on Iceland.

Raeder stated that the entire German fleet would have to be used for this purpose. However, he also said that the island could not be held against the overwhelming might of the Royal Navy, which would lead to the German forces being cut off from any supplies or reinforcements.

In the summer of 1940, Hitler did not care about Iceland because he ultimately hoped to reach a peace accord with England. In the Führer’s view, the British were the German’s natural allies, even though they heralded from a lesser Anglo-Saxon heritage as opposed to the superior Germanic Aryan race.

Negotiations between the two countries continued during this period, with Churchill adamantly refusing to bow to Hitler. Then, in 1941, the Germans invaded the Soviet Union, and this removed all threat from the small island nation to the north.

Despite all of this, Iceland’s secluded location could not entirely protect it from the events of World War II. The British didn’t know that the Germans had abandoned their attempts to invade. They felt certain they needed to act to secure the safety of this island, and they did.

At the beginning of the Second World War, Iceland was a sovereign kingdom that was nevertheless part of a political union with the Kingdom of Denmark. King Christian X was Iceland’s Head of State.

Once the war broke out with the invasion of Poland by the Germans, Iceland officially declared its neutrality. However, that did not protect the country from British diplomatic overtures regarding trade and the request for access to the island by the British Navy. The Icelandic government refused, insisting on their neutral status.

This response did not go down well with Winston Churchill who emphasized that the country should not be allowed to undermine the British war effort.

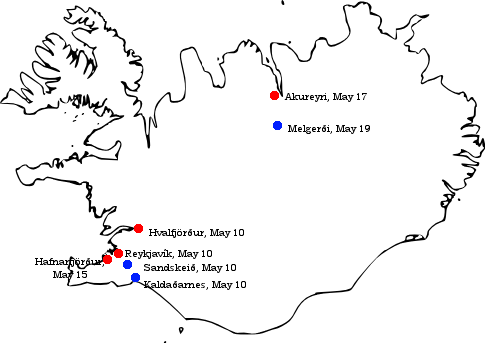

On May 10, 1940, Great Britain invaded Iceland

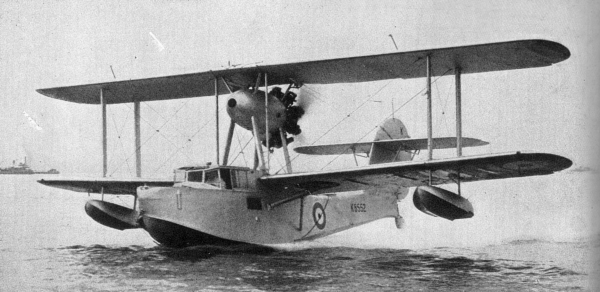

The cruisers HMS Glasgow and HMS Berwick, accompanied by the destroyers HMS Fearless and HMS Fortune, arrived at the Icelandic capital city of Reykjavik.

The trip from Scotland to Iceland had been a disaster for the British because the majority of the troops had not been conditioned for sea travel. By the time they arrived at their destination, a large part of the crew was ill. It was so bad that one Royal Marine committed suicide.

HMS Berwick photo

“In May 1940 we transported Royal Marines to Iceland and the island was occupied on the 10th May to prevent the occupation by a German force. A number of German civilians and technicians were made prisoners and transported back to the United Kingdom. Very rough seas were encountered on passage to Iceland and the majority of the marines cluttered gangways and mess-decks throughout the ship, prostrate with seasickness. One unfortunate marine committed suicide.”

— Stan Foreman, petty officer of HMS Berwick

Seasickness or not, a vastly superior British invasion force consisting of some 746 Royal Marines was to face off against 60 Icelandic police officers and 300 untrained reservists. Without a doubt, a bloodbath would ensue.

However, in reality, nothing much happened.

At about five o’clock in the morning, HMS Fearless, loaded with a complement of 400 Royal Marines, began to approach the Port of Reykjavik. By this time, a crowd of eager onlookers had assembled. The British Consul and a detachment of Icelandic police also stood by the docks.

When HMS Fearless docked, Consul Shepherd, who was uncomfortable with the large crowd, turned to the Icelandic police and asked, “Would you mind… getting the crowd to stand back a bit, so that the soldiers can get off the destroyer?” The Icelandic response was a terse, “Certainly.”

Debarkation of the British troops did not happen without incident. A more courageous and incensed Icelander grabbed a rifle belonging to a British serviceman and rammed a cigarette up the barrel. He then threw it back at him, telling him to be careful. The soldier was disciplined for his lack of professionalism.

The Occupation of Iceland, despite government protests, was good for the country

Immediately after the British arrival, the Icelandic government issued protests to the British that their neutrality had been “flagrantly violated” and “its independence infringed.”

The British responded by offering favorable business agreements, compensation, and a policy of non-interference in Icelandic domestic affairs. Furthermore, the British promised to leave after the war.

Even Winston Churchill visited Iceland personally. He tried to placate the irritated Icelandic government by saying that they were lucky that the British had got to them first. He explained that, had the Germans arrived before them, the Allies would never have let it stand. More deaths, both civilian and military, would most certainly have resulted.

In the meantime, the British continued to funnel more and more troops onto the island until at one point about 20,000 personnel were stationed there. They waited for the German invasion that never came.

As the war progressed, these soldiers were needed elsewhere, so the British asked the Americans to take over control of the island.

On July 7, 1941, a little over a year after the British invasion, the defense of Iceland was transferred from Britain to the United States. The US Marines replaced the British forces, leaving the British in control of a few airbases for strategic operations.

The 1st Marine Brigade stationed about 4,100 soldiers there until early 1942 when US Army troops replaced them, so they could join their fellow Marines fighting in the Pacific.

Life in Iceland during the war

Iceland, during this time, fully cooperated with the British and then the Americans. But, officially, the country remained neutral during the Second World War.

Ultimately, Iceland proved to be an advantageous staging point for numerous naval, aeronautical, and communications activities such as, for example, the sinking of the German battleship the Bismarck.

The country underwent massive structural changes during the war. At one point, about 25 percent of the population consisted of British and US military personnel. This had a tremendous impact on the infrastructure, requiring the construction of new bridges, roads, hospitals, and airfields all across the country.

Some Icelanders called this period “The Blessed War” because the impact on the economy would be felt for many years after the end of the Second World War. Along with the aid of the post-war Marshall Plan, Iceland morphed from an impoverished fishing nation into one of the wealthiest countries in the world.

However, this prosperity came at a price. And the cost all boiled down to one of humankind’s favorite pastimes — good old fashioned sex.

As we already mentioned, the island’s population had swelled with tens of thousands of predominately American soldiers. These men were young and hot-blooded, attributes that were very soon eagerly sampled by the native Icelandic women.

During WW2, to the chagrin of Icelandic men, 255 children were born as a result of liaisons between American or British soldiers and Icelandic women. At some point, Iceland’s authorities even punished women for frolicking with the “occupier,” but it did not help.

It was not all bad news for the island though. On June 17, 1944, Iceland dissolved its union with Denmark and the Danish monarchy and declared itself a republic.

Aftermath and Legacy

The presence of British and American troops in Iceland had a lasting effect on the country, and not just in relation to the population numbers.

The Americans maintained a strong military presence on the island all the way up to the year 2006, which had a significant economic impact covering many sectors. Overall, Iceland, except for the Financial Crisis from 2007 to 2009, enjoyed unprecedented economic growth.

So, even though it was unsanctioned according to political etiquette, the British breach of Iceland’s neutrality during the war brought more benefits than disadvantages.