The next day the Honduran team was transferred to the stadium in armored vehicles.

The history of human kind has seen a number of wars that started over awkward reasons. One such war in more recent times was the 1969 Football War or the Soccer War. It was a brief conflict between El Salvador and Honduras, two neighboring countries in Central America. Aside from its almost comical name, it is one of the shorter wars in history, lasting a mere 100 hours.

Even though events that occurred during the soccer matches between two national teams contributed to the development of the conflict, the reasons for the war went far beyond a sports rivalry.

Banana Republic vs. Coffee Republic

Since becoming independent states in the first half of the 19th century, Honduras and El Salvador both developed under the influence of big international agriculture companies, primarily from the United States. In El Salvador it was coffee, in Honduras it was bananas that attracted big players. In the 1960’s both countries were still undeveloped, with high percentage of people living below the edge of poverty.

El Salvador was the first of the two to begin the process of industrialization. That strengthened the weak economy of the country, but also proved to be a big problem: it made El Salvador an overpopulated country. Even though it was five times smaller than neighboring Honduras, El Salvador had a population of 3.7 million while Honduras had only 2.6 million.

This disproportion caused an enormous number of unemployed Salvadorans to look for a better life and a piece of land to cultivate in Honduras. As years passed, the number of Salvadoran immigrants in Honduras increased to 300,000 people. Most of them were plain squatters, who claimed the right to the land they cultivated only by the fact that they lived there.

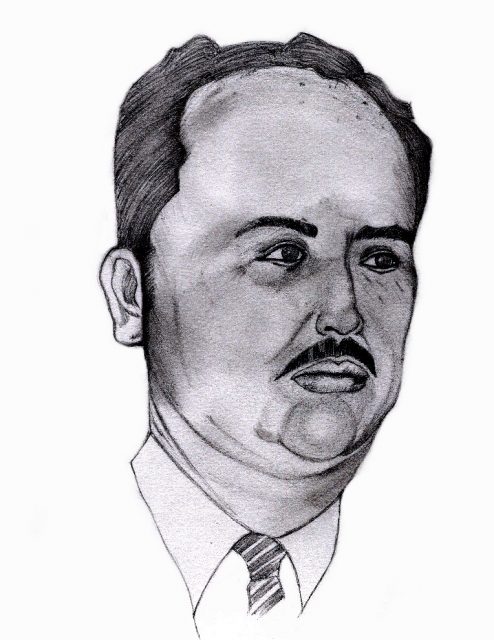

Even though Honduras was much larger and a country with bigger potential, it also had problems of its own. Under the rule of military dictator Oswaldo Lopez Arellano, Honduras was struggling to build an effective government and stable economy.

Among the most discontented citizens were Honduran farmers, who were unsatisfied with the distribution of cultivated land and were asking for agrarian reforms. Since most of the land was in hands of big corporations—sponsors of the regime—the only land that could be taken into consideration was that which had been settled by Salvadoran immigrants.

Salvadoran Scapegoats

On the eve of the 1960’s situation in Honduras became bad. The country was suffering a deterioration of its political and economic situation. As its government looked for an excuse for its incompetence, Salvadoran immigrants popped up as the best choice. They were pinpointed as the sole reason for low wages and high unemployment.

The government started a media campaign against Salvadorans, which raised the public discontent with their presence. Salvadorans begun to suffer maltreatment on a daily basis both from the government and ordinary people.

A moment that marked the beginning of conflict between the two nations was the Honduras government’s decision in April 1969 to expel from their lands all those that were not Hondurans by birth. It meant that thousands of Salvadorans had to move back to their homeland.

Naturally, this was a great problem for El Salvador which had huge problems with overpopulation. The Salvadoran government strongly protested against the actions taken by Hondurans, but received no response. The media in El Salvador then begun a campaign of their own, reporting on violence against Salvadorans.

The Road to the World Cup and to the War

An unlucky course of events made the situation even worse. The two countries were scheduled to meet in a semifinal qualification round for the 1970 World Cup in Mexico. After recent events, the rivalry was so high that incidents were unavoidable.

The first match was played on June 8, 1969 in the Honduran capital, Tegucigalpa. In an atmosphere full of tension, Honduras won the match by an injury time goal. While Hondurans were celebrating, Salvadorans felt they were robbed.

To make things worse, an 18-year-old Salvadoran girl named Amelia Bolanios took the defeat so hard that she killed herself after the referee blew the final whistle. Her suicide made her a national hero and also boosted the hatred toward Honduras.

There was nothing good to expect from the rematch in San Salvador one week later. Salvadoran fans made sure that guest players felt they were not welcome. For the entire night before the match, fans made a terrible amount of noise in front of the hotel where the Honduran players were located.

The next day the Honduran team was transferred to the stadium in armored vehicles. El Salvador easily won the match by three goals to null. To insult their rivals even more, Salvadorans raised a dirty rag instead of the Honduran flag. On top of everything else, two Honduran fans were murdered on their way home, while many others ended up with severe wounds.

It is needless to say that these incidents caused severe reactions in Honduras, where local Salvadorans experienced huge reprisals. Their shops were demolished and the owners beat up, with some of them even murdered. The border between the two countries was closed, and in the days that followed approximately 1,400 Salvadorans were being expelled from Honduras per day.

The third decisive match was played in Mexico City on June 26. In a tight match, El Salvador won 3-2 after extra time. On the same day, the government of El Salvador dissolved diplomatic ties with Honduras. They were objecting that Honduras did nothing to prevent the maltreatment of Salvadorans, nor to punish those who did it.

The real war

Salvadorans were resolved to solve the dispute through the means of force. On July 12, 1969 the Salvadoran and Honduran armies engaged in border clashes, but two days later the conflict erupted into war.

On the afternoon of July 14, the army of El Salvador made a coordinated attack from the air and on the ground. Its air force made an attack on Honduras’ main airport in Toncotin with three passenger Douglas C-47s followed by F4U-5 Corsairs. The C-47s had been modified to serve as bombers by attaching explosives to their wings.

On the ground, their army of around 15,000 soldiers crossed the border along two main roads that connected the countries. The northern group consisted of one small armored vehicles unit and a large number of infantrymen. To the east, on the other hand, were engaged more powerful units that included M3 Stuart tanks and 105mm M101 field howitzers. These units were aiming for the city of Tegucigalpa.

By the end of the following day, Salvadorans made significant progress as Honduran ground forces were no match for their strength. However, Hondurans did have an ace up their sleeve. On July 16, the Honduras Air Force sent T-28 Trojans, F-41s and F4U-5 Corsairs to attack the Ilopango air base, oil facilities in the Acajutla Port, and other smaller oil facilities.

These attacks had immediate results, since because of the resulting gasoline shortage, Salvadoran forces had to halt their operations. However, they were still eager to attack Tegucigalpa even if they had to do it on foot.

OAS to the rescue

Facing a fatal scenario, the Honduran government appealed to the Organization of American States (OAS) to intervene. In an urgent session on July 18, the OAS called for an immediate ceasefire and a withdrawal of Salvadoran troops from Honduras.

El Salvador agreed on the ceasefire starting from July 20, but refused to withdraw its troops until Honduras was obliged to pay reparations to victimized Salvadorans and guaranteed the safety of those who remained in Honduras. Only after the OAS pressured them with economic sanctions did El Salvador agree to withdraw its troops on August 2. After only four days, the war was over.

Even though it was a brief conflict, the war caused more than 2,000 casualties, primarily Honduran civilians. The majority of those living in combat zones had their houses burned down or demolished.

Diplomatic relations between the two countries were suspended for years and the border was closed. The war affected the economies not only of Honduras and El Salvador but also those of the entire region, because it suspended the program of Central American Common Market for 22 years.

El Salvador was the greater loser of the war. Between 60,000 and 130,000 Salvadorans were expelled from Honduras. The Salvadoran government was unable to cope with such an inflow of people, causing social unrest in the country which ultimately led to a civil war.

The two countries signed a peace treaty eleven years later, on October 30, 1980. On November 23 that same year, the two nations played their first post-war soccer match. El Salvador won 2-1.