The outbreak of war can do a strange thing to man’s temperament. A student, businessman or teacher can be civilly performing their duties one year, and then in the next, be fully immersed in the savagery of war. For banker George Albert Cairns, war would transform him from a polite bank employee in 1941 into a shining example of gallantry in 1944 as he charged up a hill with but one arm, holding the sword which a Japanese soldier had used to inflict the terrible wound.

During a brutal exchange in Burma, British and Japanese soldiers had somehow inexplicably dug in adjacent to one another without the other knowing the enemy was close.

The following morning, when they discovered their situation, a savage hilltop fight began. The melee quickly turned into hand-to-hand combat, and as the Japanese brandished their swords, the British stabbed with their bayonets, and the Gurkhas swung their kukri. Lt. Cairns was giving as good as he was getting when a Japanese soldier sliced off his left arm with a sword.

With ample reason to bow out of the fight, Cairns did the inexplicable. He shot the Japanese soldier who had taken his arm, then retrieved the sword. Cairns could then be seen charging up the hill equipped with the sword that had delivered the awful wound. Cairns would later fall in the battle, but not before rallying his men to victory. For his actions, he would be awarded the Victoria Cross and the eternal respect of all who would see him fight that day.

From Banks to Burma

George Cairns was born in 1913, in London, just before the nation was pulled into the horror of the First World War. By the time he came of age and began to set out on his own professional career, the world had come full circle back to war again.

Having worked successfully at the bank and marrying a fellow employee, in another world Cairns would seem to be setting out on a peaceful and happy life. However, war would have other plans for Cairns.

In 1942, he joined the war effort and was attached to the South Staffordshire Regiment in Burma. This Chindit unit was used for long range reconnaissance and disruption of enemy activity and was part of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade. This unit was under the command of Brigadier Michael Calvert and would see some of the fiercest jungle warfare of the entire conflict.

By March 1944, Cairns found himself pushing through the jungles of Burma in yet another long range mission. At the end of another hard day, as evening began to set in, the unit opted to dig in for the night. On a hill nearby stood a large Pagoda which dominated the landscape.

By their estimation, the Japanese were not in the area, and it seemed as good as any other. Unfortunately, it transpired that the Japanese were right next door making the same assessment. Remarkably, that night, neither seemed to be aware the other was there. When morning broke a different story would unfold.

An Unwelcome Surprise

At some point that morning the British came across some Japanese soldiers and it was clear the enemy was in the area. At around 11:00 am, the entire hill erupted into a storm of fire. The Staffords began to advance up the hill only to once again find the Japanese with a similar idea.

The two forces charged at one another, the destruction of the enemy the only thing in mind. Sometimes the author of an article can provide some important insight into an event, but in this case, it is remarkable to hear the account from General Michael Calvert himself as few could describe it in better detail:

“A number of the first wave of Staffords were now in front of me, scrambling up the slope without a pause as if the whole thing had been their idea and they couldn’t wait to get at the enemy’s throat. I was close on their heels at the top and it now occurred to me that the Japanese had been strangely quiet.

“Some shots had come down at us but not as many as I had expected, which probably meant we had regained the initiative by then and taken them unawares. Then, to my surprise, the Japanese leaped up as we went at them and charged into us. Two sides charging at each other was certainly not going according to the military rule books.

“We clashed in an area of about fifty square yards on the hilltop and the air was filled with the sound of steel crashing against steel, the screams and curses of wounded men, the sharp crack of revolver and rifle shots, the eerie whine of stray bullets and the sickening crunch of breaking bones.

“Everybody slashed and bashed at the enemy with any weapon that came to hand, yelling and shouting as they did so. In Europe, the cold steel part of it would have been restricted to bayonets; out here there was more variety, with the Japanese officers wielding their huge swords and the Gurkhas doing sterling work with the kukri, the curved knife they used with such deadly effect.

“The official report I quoted earlier summed it up: ‘The characteristic of this fighting was its savagery… rifle and bayonet against two-handed feudal sword, kukri against bayonet, no quarter to the wounded …’

“In front of me I saw a young Staffords subaltern, Lieutenant Cairns, attacked by a Japanese officer who viciously hacked off his arm with a sword. Cairns shot the Japanese point-blank, flung away his revolver and picked up the sword that had maimed him before leading his men on, slashing fiercely at any Japanese within his reach.

“Finally, he dropped to the ground mortally wounded, but that gallant youngster refused to die until the battle was over. I was able to speak to him before he closed his eyes for the last time. ‘Have we won, sir? Was it all right? Did we do our stuff? Don’t worry about me.’

“Is it any wonder that, so many years later, some of us still have nightmares? There is glory in a fight like this. But there is horror in it, too, as young lives are brought abruptly and brutally to an end and young bodies maimed and made useless. Later Cairns was awarded the Victoria Cross; but he never knew it.

“At the time, of course, there is no room for such thoughts as these, no room for anything except the fight. I can still remember the faithful Young and Dermody battling at my side, Young shouting anxiously, ‘Be careful, sir, be careful’ as he shot at any Japanese who came within his vision.

“Then, at last, we drove them back behind the pagoda and there was a brief intermission as both sides lobbed grenades over and around the battered house of worship; fortunately the Japanese grenade has a lot of bark but not much bite, so they did little harm. But they added to the noise and confusion and I found it difficult to think out our next step amid the shambles of the battleground.”

Brigadier General Michael Calvert

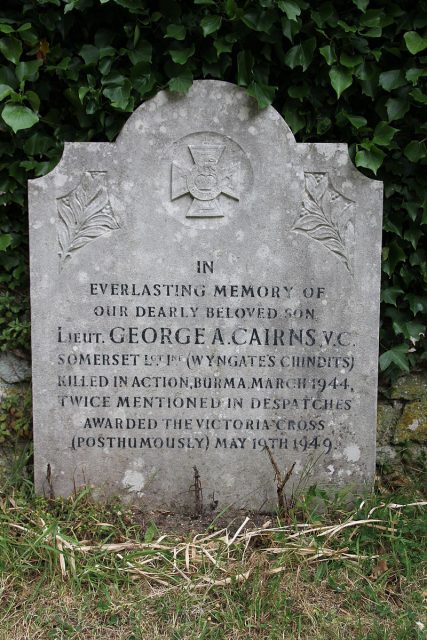

An Honor Delayed

As already stated, George Cairns would be awarded the Victoria Cross for his actions in the savage battle. His honor, however, would be delayed and one of the last to be gazetted after the war. The original recommendation for Cairns VC went down when the reviewing General’s plane crashed with the only written record of it on board. By the time the news of Cairns actions circulated, several of the original witnesses to Cairns gallantry had themselves died in the war. However, gallantry this inexplicable could not be denied forever. In May 1949 he received his due and rightful honor along with a hallowed place in the halls of military history.