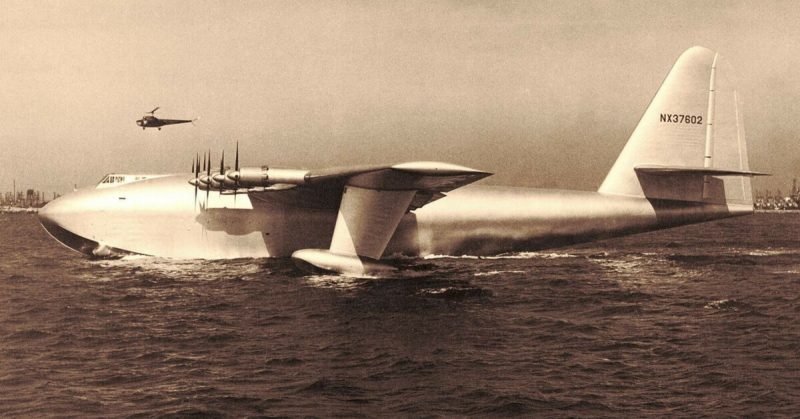

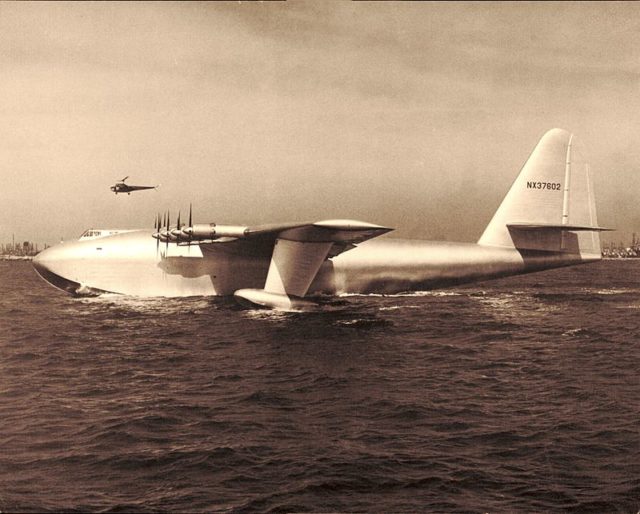

It is the biggest plane ever built – standing more than five stories tall, with a wingspan longer than a football field. Able to carry over 700 people, it was constructed almost entirely from wood. Sadly, it only flew once.

When America entered WWII and joined the Allies, it faced a major problem. How to get people, equipment, and goods to the British Isles without getting sunk by German U-boats? Compounding that problem was a shortage of metal.

James Vernon Martin, an American aviator, invented the automatic stabilizer and retractable landing gear (among others) that are a standard feature in planes today. His solution to German U-boats was the Martin “Ocean Plane” Flying Boat. Sadly, no one was interested.

Except for British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, that is. Unfortunately, Britain’s treasury was not willing to pay for it, so Churchill told President Franklin D. Roosevelt about the concept. Intrigued, Roosevelt broached the subject to industrialist Henry John Kaiser – founder of Kaiser Shipyards, Kaiser Permanente, and so much more.

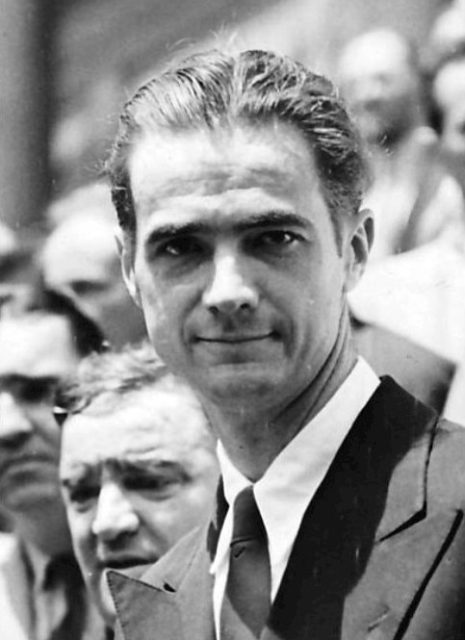

Kaiser knew just the man who could pull off such a thing – Howard Robard Hughes Jr. In his mid-20s, Hughes was already famous as a Hollywood producer, engineer, inventor, and aviator who had set several world records in his planes. Hughes loved challenges, so he agreed to join Kaiser in making the flying boat a reality.

The military was not going to make it easy. Priority went to building conventional planes, tanks, boats, and weapons, so they could not use any metal; not even aluminum. The flying boat was required to carry at least 750 men or more. Tanks and other heavy equipment, too, if possible.

Despite his genius for invention, Hughes had never had any formal training in engineering. He had dropped out of college to make movies and was mostly self-taught. He did have an expert – Glenn Odenkirk. It became apparent to Hughes the most abundant material available was wood – the least ideal material for building large planes.

Industrialized metal sheets have uniform weight, consistency, and tensile strength – important factors in plane design. Wood, however, has no such uniformity. It all depends on the tree, the climate it grew in, the season it was cut in, and so on.

Building small, functional planes out of wood was one thing. One that could fulfill the specifications was quite another. Every individual piece of timber had to be considered. Still, Hughes could not resist.

Consulting wood specialists, they settled on birch and spruce. The Hughes Aircraft Company left that to the Roddis Manufacturing firm which specialized in making a plywood-and-resin product known as Duramold.

Kaiser’s expertise in shipbuilding and Hughes’ experience in designing experimental planes, was a perfect match; at first.

In November 1942, the government gave them $18 million ($274,674,193.55 today) to test, develop, and produce three. The men called it the HK-1 (“H” for Hughes and “K” for Kaiser) plane and got to work.

To meet the military’s specifications, the HK-1 had to have a wingspan of 320’ and a wing area of 11,430 square feet. It had to be 218’ 6” in length, with a tail 80’ tall, and a tail span of 113’ 6”. To hold 165,000 cubic feet of cargo, it needed a fuselage 30’ 6” high and 24’ 5” wide.

To make it fly, however, they needed eight Pratt & Whitney R-4360 Wasp Major radials – each producing 3,000 hp. No such thing existed, however, so they had to be made from scratch. They also needed eight 4-bladed Hamilton Standards measuring 17’ 2” in diameter – also from scratch.

The whole thing ended up weighing 400,000 pounds with a maximum payload of 130,000 pounds. That gave the plane an estimated cruise speed of 175 mph (maximum 218 mph) for a distance of 3,000 miles at a height of 20,900 feet – enough to reach Britain and avoid those nasty U-boats below.

There were two problems. The first had to do with the government. Kaiser complained about how slow they were to release materials and money for the project. The second had to do with Hughes.

He was a perfectionist who micromanaged even the smallest details and often made design changes. He was obsessed with everything – from the chairs to the layout of the control panel. Kaiser finally had enough and bailed, so Hughes renamed it the H4 Hercules. Everyone else called it the “Flying Lumberyard” or the “Spruce Goose.”

With the government breathing down his neck, construction finally started in 1944. Given the plane’s size, it could not be piloted with normal controls. Hughes and Odenkirk designed the artificial “feel” system used in today’s planes.

For every pound of pressure exerted on the cockpit’s rudder, 2oo pounds would be exerted on the rear rudder with a system of hydraulic pumps. Cockpit controls also triggered hydraulic fluid which forced pressurized oil in a cylinder that moved the control surface at the plane’s rear.

As the plane took shape, Hughes could not stop micromanaging. By 1944, America had pulled itself out of the Depression, industries were booming, and metal was no longer in short supply. Better yet, technology had reached the point where U-boats were no longer a significant threat.

By 1945, the government wanted to pull the plug on the project, but Hughes used his influence to see one plane financed. The government agreed. WWII ended, and the plane was still under construction – again because of Hughes’ constant interference.

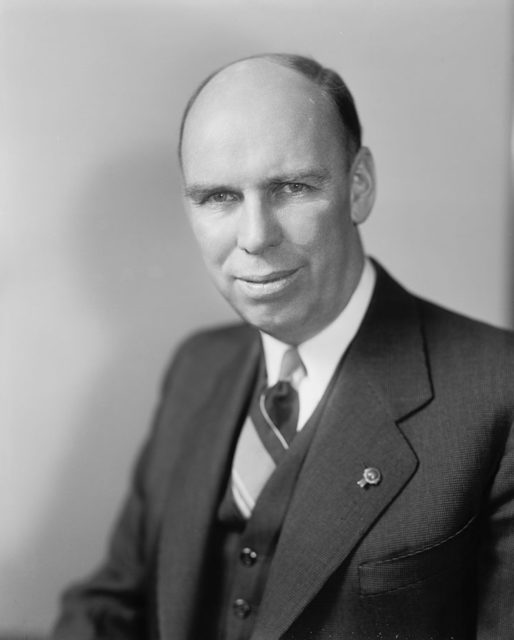

The government had had enough. By then, the War Department had poured $40 million ($440,046,511.63 today) into the project with nothing to show for it. In August 1947, Ralph Owen Brewster (then the Republican Senator for Maine) set up a Senate War Investigating Committee to look into Hughes’ “misappropriation of government funds.”

Hughes was acquitted of any wrongdoing. However, he had to prove the plane worked or he could kiss his military contracts goodbye. Built in Playa Vista, Los Angeles, it was transported in three pieces to Long Beach – requiring road closures and streets lined with an over-awed public.

Once assembled, Hughes took it for a test run on November 2, 1947, with members of the press. It was not supposed to fly, only travel through the waters of Cabrillo Beach. To everyone’s surprise (including Hughes), it flew to 70 feet for a mile at 135 mph – proving it worked. Even so, it was no longer necessary and never flew again.

It now rests at the Evergreen Aviation Museum in McMinnville, Oregon.