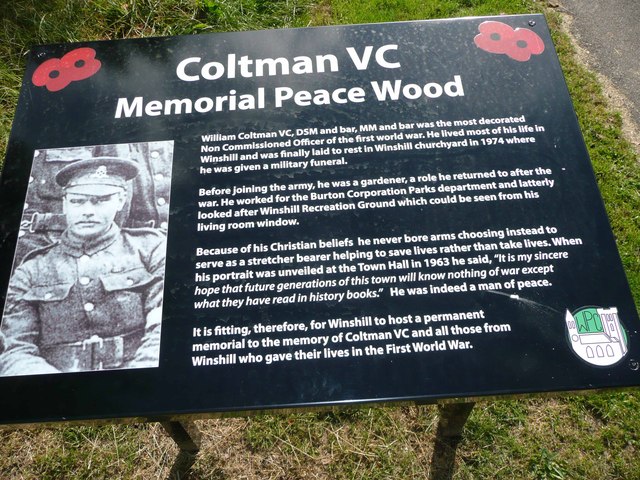

His actions in the First World War earned him numerous decorations. But interestingly, none of his award-worthy war actions involved using any weapons. Indeed, William Harold Coltman was a staunchly religious fellow and conscientious objector to war.

Born on December 27, 1891 in Rangemore, in the suburbs of Burton, Staffordshire, Coltman grew up to become a committed associate of the Plymouth Brethren. He worked on weekdays as a market gardener and served as a Sunday School teacher on weekends.

But the outbreak of WWI saw the conscription of many able-bodied men by the British government. Solid in his Christian beliefs, Coltman promptly became a conscientious objector.

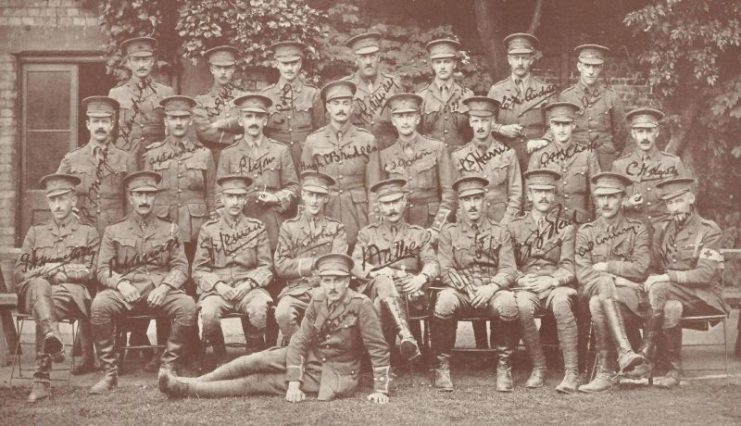

However, due to the way the law treated conscientious objectors, Coltman took a more compromising position. He applied for a non-combatant role. Following his enlistment, he became a stretcher bearer in the 1/6th Battalion of The North Staffordshire Regiment.

Before he received any awards, Coltman’s impressive service got him Mentioned in Dispatches.

Then, on a cold, misty night in February 1917, an officer led a wiring party into no man’s land. Wiring parties had the role of sabotaging the enemy’s wire obstacles, as well as installing new wires for themselves and repairing existing ones. It was a risky, daunting task.

The wiring party that night worked under the cover of the darkness and the mist. But then the mist slowly cleared, and enemy troops discovered their presence. Hostilities ensued.

As the enemy’s guns flamed, the officer suffered a gunshot wound to his thigh. Coltman earned his first Military Medal for rescuing this officer.

He got a bar added to his Military Medal in August 1917 for three separate gallant actions in June. First, when mortar fires hit an ammunition dump, Coltman took initiative to remove Verey lights from the ammunition dump.

The next day would see the mortars strike again. Several men suffered injuries as the company’s headquarters was struck. Coltman was notable for the energy and the devotion he showed while tending to wounded comrades.About a week after, Coltman lead a team who dug out and rescued a group of soldiers who were trapped under a collapsed trench tunnel.

In July 1917, Coltman was remarkably active in rescuing the wounded under heavy enemy shell fire. He braved the devastated frontlines, searching for injured comrades as explosions lit up the night.

Such “absolute indifference to danger” not only ended up saving numerous lives, but it also became a source of inspiration for others, and earned him his first Distinguished Conduct Medal (DCM).

On 29 September 1918, during hostilities near St. Quentin Canal, Coltman was all over the place, disregarding the risks in the face of fierce artillery fire that rapidly struck down his comrades. He dressed many casualties and helped evacuate them.

He kept doing his duty without rest and worked the next day during a second advance. Neither shell nor machine gun fire could make him turn around. He searched all over the hostile zone for injured men and would not stop until it was clear that all wounded soldiers were safe.

Coltman’s exceptional fearlessness during that time earned him a second DCM award. And just a week after this last display of gallantry, he performed the deed which made him a recipient of the Victoria Cross.

During operations at Mannequin Hill from 3-4 October, Coltman, who was by then a lance corporal, heard that some wounded soldiers had been left behind during a retreat.

He promptly ran into the hostile zone. He searched for his comrades under heavy enfilade fire, found them, and dressed their wounds. Then on three consecutive instances, he raced to safety, carrying his comrades on his back. For two days, Coltman tended to the wounded.

For his extraordinary commitment and courage, he had more grateful comrades than he could count. On May 22, 1919, King George V honored him with the Victoria Cross, the most prestigious British military honor.

After the war, Coltman went back to Burton and worked as a gardener.

When the outbreak of World War II occurred in 1939, Coltman was back on duty. This time he was a commissioned officer with the Army Cadet Force. In 1951, Coltman resigned his commission, and he retired in 1963. After his death in 1974, he was buried in Saint Mark’s Churchyard in the town of Winshill.

His Victoria Cross and the other medals he earned during his lifetime are preserved and displayed at the Staffordshire Regiment Museum. The museum also features a replica of a WWI trench as a major outdoor exhibit, and it is named after William Coltman.

Coltman achieved such fame, served his country with utmost dedication, and became the most decorated non-commissioned officer of WWI, all without firing a shot.