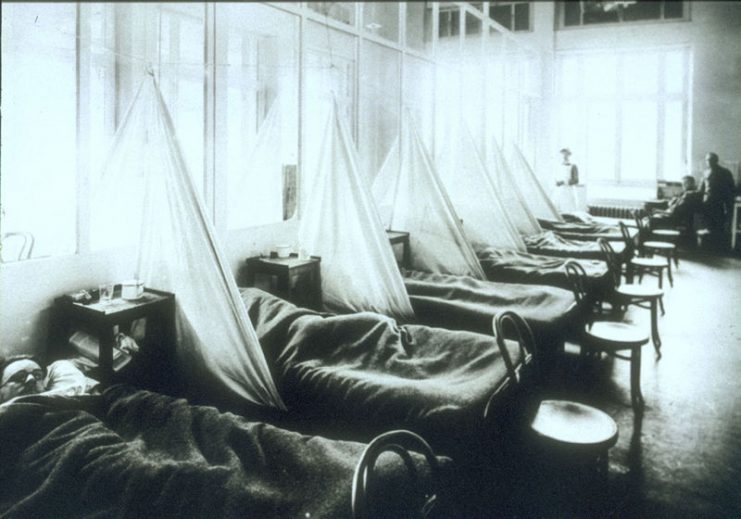

The weaker patients had a higher chance of survival. It was the young and healthy that experienced a higher mortality rate.

While Denmark remained neutral during the First World War, the fact that they shared a border with Germany meant that involvement in the war in some form of another was an inevitability, despite the Danes’ commitment to neutrality during the conflict.

While no battles were fought on or near Danish soil, Danish ground did end up becoming a permanent resting place for a number of Allied troops who tragically perished on the way back to their home countries after the war was over.

Allied troops from as far afield as India, Tasmania and Canada were buried in Copenhagen’s Vestre cemetery, with some of them having succumbed to a foe that caused more deaths than the war itself: Spanish flu.

While it is estimated that around ten million troops lost their lives in the First World War, and a couple million civilians too, the death toll of the Spanish flu pandemic, which ravaged large swathes of the globe throughout 1918 and early 1919, is estimated to have killed between fifty million and one hundred million people across the globe, making it one of the most devastating pandemics in history.

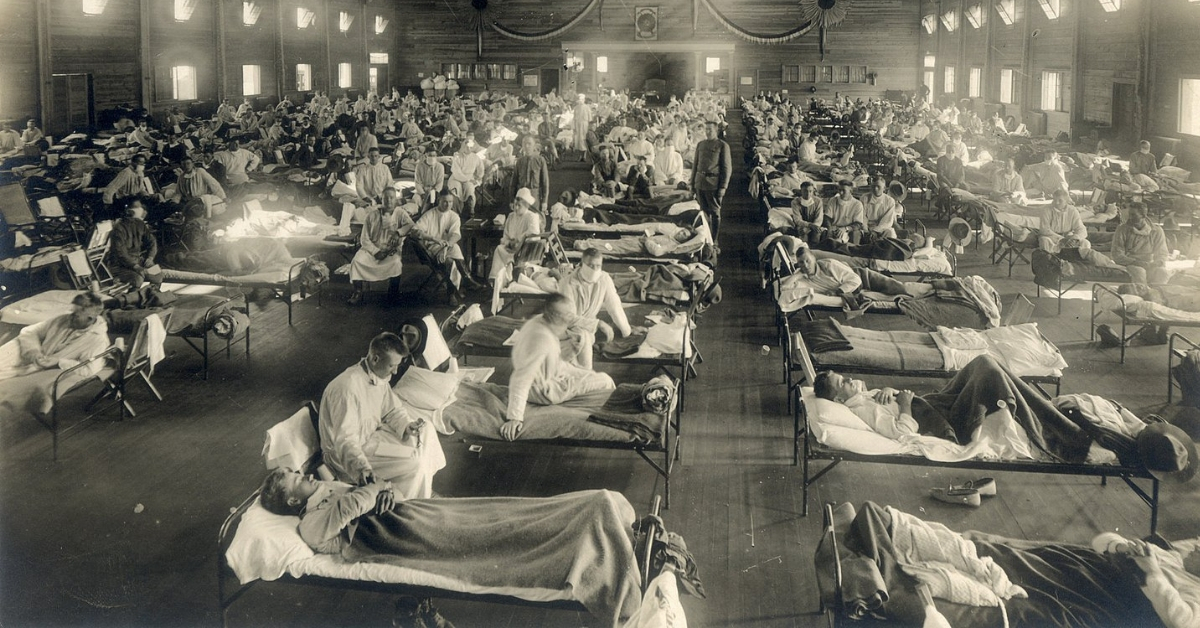

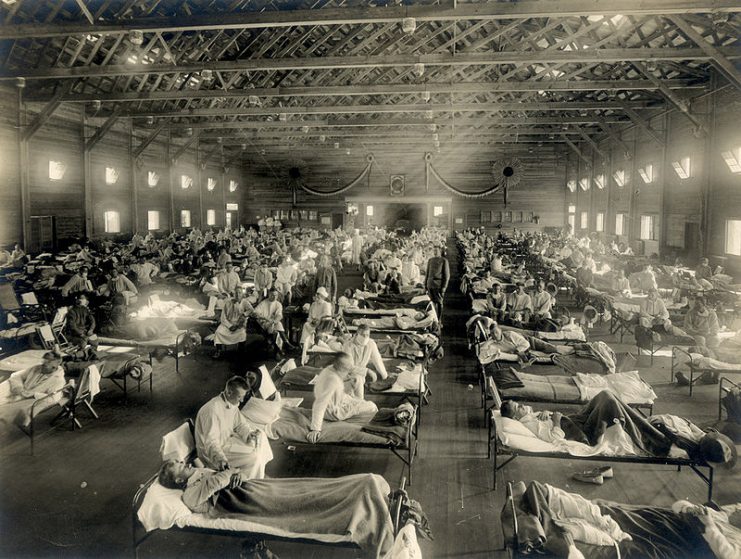

The First World War contributed significantly to the spread of the disease. Masses of troops on all sides were packed in close quarters and unsanitary conditions, and the budgets of the nations involved in the war were too stretched and strained to give the flu epidemic the necessary attention to stop it.

Millions of troops fell victim to the disease, and whether from being weakened due to battle wounds, malnutrition in the trenches, or simply having their immune systems compromised from the stress of the conflict, it took a heavy toll on the armies of the First World War.

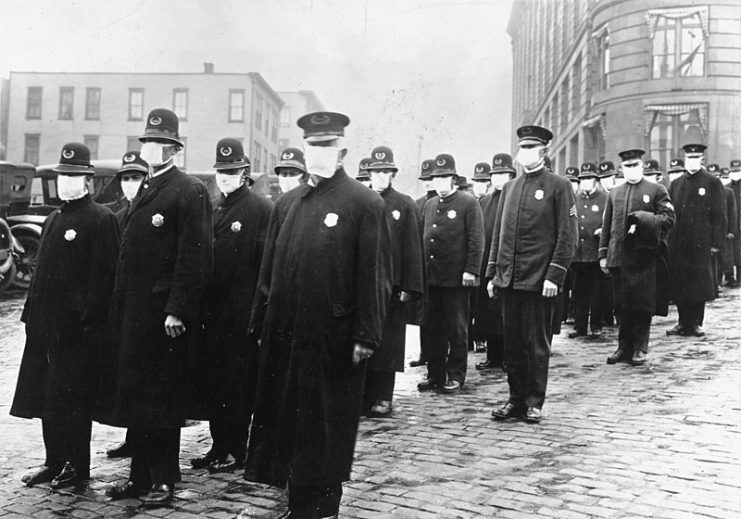

In fact, the name “Spanish flu” was not given to the disease because it originated in Spain, but rather because Spain was neutral during the war, and thus free to accurately report the statistics concerning the vast numbers of its citizens who had died as a result of the flu.

Nations involved in the First World War, afraid of lowering troop morale and public support for a war that was becoming increasingly unpopular, censored their statistics about just how many troops had died as a result of the pandemic.

It was an especially bitter and tragic time for the Spanish flu pandemic to break out as well – the first cases were actually reported in Kansas in March 1918, and the flu is likely to have been carried to Europe by American troops heading for the trenches of WWI.

Just as the war was wrapping up and peace was on the horizon, this new killer, more deadly than machine guns, artillery shells or poisonous gases, ripped through the armies, striking down men regardless of rank or nationality. It paid no heed to the Armistice of November 11, 1918, continuing to kill millions until well into 1919.

And this was how many of the Allied troops came to be buried in Denmark’s Vestre cemetery. After surviving the brutality of the trenches, and the subsequent misery of being prisoners of war in Germany’s POW camps (in which many were incarcerated for years), they were finally on their way home, free of war and imprisonment and looking forward to returning to their families, homes, and loved ones when this new, merciless enemy struck them.

The troops who passed away in Denmark were there because of the Danish Scheme, implemented by Captain Charles Cabry Dix of the Royal Navy, in which British and Commonwealth prisoners of war who had been held in German POW camps east of the Elba River in Germany would be transported out of Germany via Denmark to ships that would take them home.

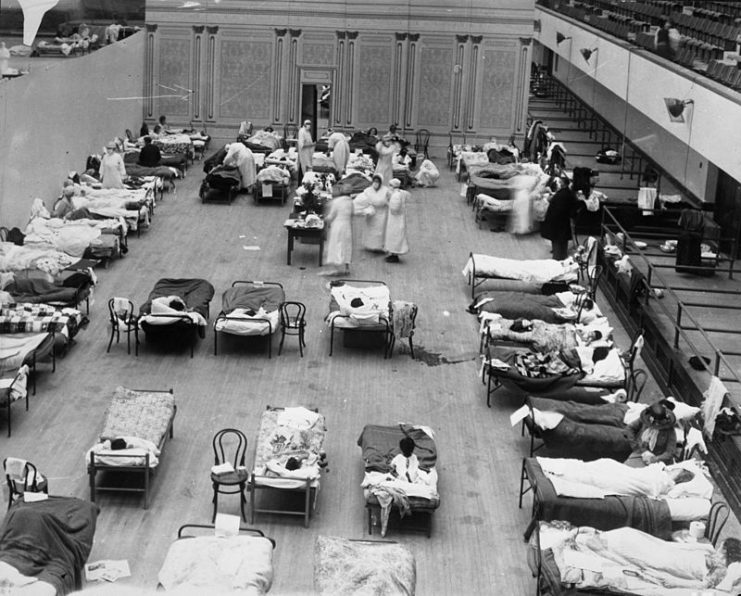

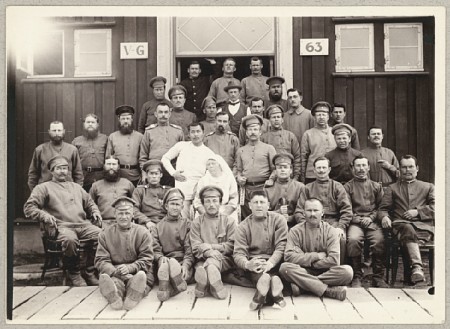

An estimated 40,000 troops made their way home via this route. Some of these men, though, were suffering from battle wounds, or were simply generally weak from long periods of incarceration in German prison camps, and were kept in Danish camps to be treated by Danish nurses and doctors and strengthened for their journeys home. A number of them, sadly, never made it out of these Danish camps.

Spanish flu had hit Denmark hard – just as it had hit many European countries, and at the time that the Danish Scheme was implemented, Denmark’s hospitals were already bursting at the seams with patients infected with the flu, and Danish medical resources were already stretched beyond capacity.

Nonetheless, the Danish doctors and nurses did their best to care for the British and Commonwealth troops who were passing through the camps. Against the deadly Spanish flu, though, there was little that could be done.

Read another story from us: Filtering War: Kleenex Fights the Horrors of Gas Warfare

It was so virulent that even men and women in the prime of their lives, strong and healthy, could be dead within days of contracting it. Weak and battle-wounded troops didn’t stand much of a chance if they became infected.

All in all, nineteen British and Commonwealth troops died in the Danish camps. They have been commemorated by a large memorial in Copenhagen’s Vestre Cemetery, and the sacrifice they made has not been forgotten, even though they are buried far from their homes.