The idea of an air raid on mainland American soil during WWII sounds crazy. Sometimes also referred to as the Battle of Los Angeles, the Great Los Angeles Air Raid took place over two days in February 1942, although it does not get a lot of publicity.

Occurring just a few months after the United States entered the war, there were reports of suspicious aerial activity in the area. Some thought they were to do with attacking forces from Japan, while conspiracy theorists contributed it to extraterrestrials.

However, the Secretary of the Navy at the time, Frank Knox, spoke at a press conference shortly after the two-day event and said it was a “false alarm.” Obviously, the media immediately had a field day and wondered what exactly was going on and whether there was a mystery to solve.

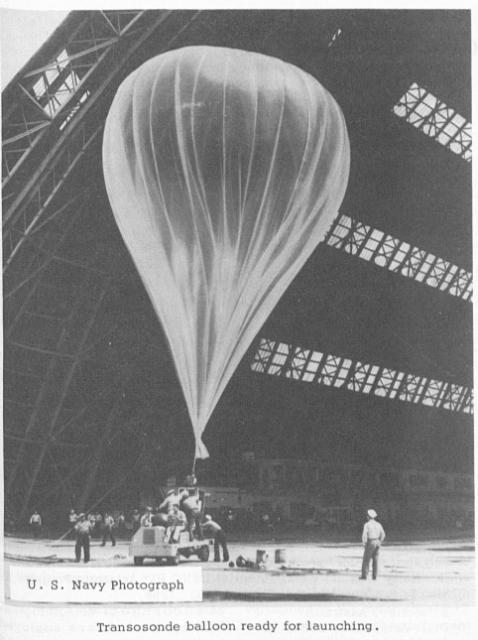

The US Coast Artillery Association saw a meteorological balloon that had been sent up in the middle of the night. One of their members shot at it, causing a panic, and then everyone began shooting into the night sky, at quite literally nothing.

The Start of the “Air Raid.”

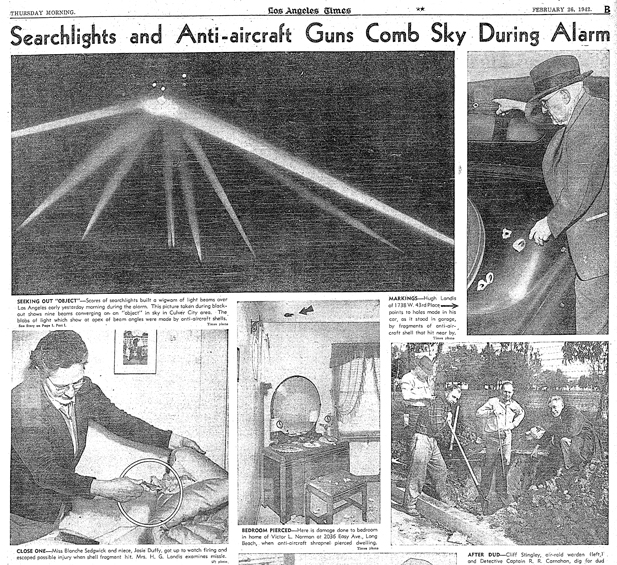

Late on the night of February 24, the air raid sirens went off in Los Angeles. Better safe than sorry, the powers that be ordered a total blackout for the entire county. At a little after 3 AM, the 37th US Coast Artillery Brigade started firing into the sky and continued for about an hour. They shot more than 1,400 shells. Around 7 AM the next morning it was declared there was nothing to fear and the blackout was lifted.

In an ironic twist of fate, there were five civilian deaths caused by the incident. Two people had heart attacks due to fear and stress, and three died in car accidents in the initial panic.

Press Response

The press responded immediately, and the “attack” was front-page news and had mass media coverage across America. A press conference was held shortly after the incident occurred, stating it was a false alarm, caused by some itchy trigger fingers and bad nerves. Then, the Army released a statement saying the event could have been caused by psychological warfare – the Japanese using commercial aircraft to cause panic.

The press speculated there was more to the story and rumors of what could have occurred circulated widely. Some of the theories included that the Japanese may have a secret base in Mexico, or that the Japanese were carrying planes over to the United States with submarines. Others thought the whole thing was staged.

After the war, the Japanese claimed they never had any planes in the vicinity at any time, but that they did have aircraft in Seattle.

Much, Much Later

Not until 1983 did the government address the situation again. The Office of Air Force History delivered a statement recognizing that, when the incident occurred, there was a significant amount of panic among the armed forces.

It was partially due to what had happened just the day before, on February 23. A Japanese submarine had appeared off the coast of Santa Barbara, shooting 13 shells into refinery installations. While the attack had done no damage, it was frightening, and the planes that were sent to destroy the submarine were unsuccessful.

Stories and rumors abounded. If Japanese subs were causing such insignificant damage could it be a ruse meant to throw the US armed forces off their scent? Did they have a much larger, more dangerous force elsewhere? Were they planning to hit a much more significant target on the California coast? Some people were predicting the Japanese would try to hit Los Angeles, and soon. The situation was ripe for panic.

In their statement, the Office of Air Force History advised some reports did include sighting enemy planes, although they were never proven. The only confirmed report was the sighting of a balloon carrying a red flare. Tons of conflicting proclamations were submitted with everyone seeing something different. It was supposed that in many cases, individuals saw anti-aircraft shells bursting, and assumed they were planes. Opinions stated everything from one to hundreds of planes were flying over the area also differing significantly as to how high and fast the supposed planes were flying.

There were even reports that some of the planes crashed, with one saying an enemy plane had landed in flames in the middle of a street in Hollywood.

Many public figures referred to the incident during the days, months and years afterward, including one individual from England who assured Americans that when an air raid occurred, they would know. It is widely assumed the War Department did not want to fully address the situation at the time because to admit they were firing at nothing, would acknowledge that they were inept.