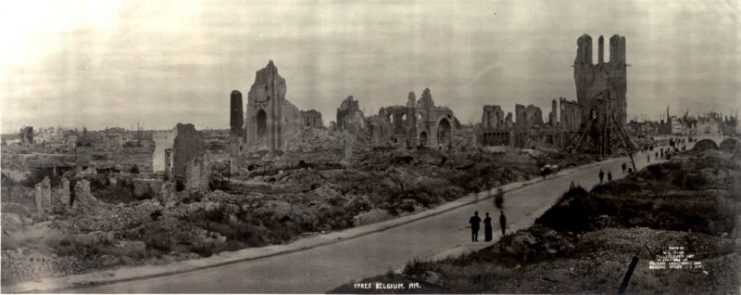

Ieper, Ypres, or “Wipers” as it was nicknamed—I’ve been to the Belgian town dozens of times before. I can even remember my first visit here when I was an 11 year old schoolboy on a trip from the UK.

I remember what seemed to be a huge cultural difference as we ran in and out of all the tobacconist shops buying bangers and Belgian chocolates. I remember how well behaved the Belgian children seemed to be compared to us English kids.

I also remember the irony of the fashion of the day. All the boys on the coach wore chino trousers and shirts. Brown leather flying jackets with mock American flight patches on them and blood chits sewn inside. Everyone had headphones from their Walkmans hanging around their necks as if they were crewmembers from a bomber.

It was as if we were all young soldiers or airmen on leave from a fake army. An army had come to liberate a nation from a pretend war. The coach smelled of hairspray from the seats occupied by the girls and brylcreem from those of the boys.

I have vague memories of visiting museums while in Ypres. The sort of museums that, sadly, no longer exist. The sort where you could pick up a rusty helmet and put it upon your head before prodding your best friend with an equally rusty bayonet, too young to worry about tetanus. No thought was given to who wore the helmet or who had carried the bayonet. They were merely props to amuse us.

Jumping from shell hole to trench, from pillbox to firing step, those chinos took a hell of a walloping that day. Ripped from concrete, torn on old barbed wire, muddied from the craters.

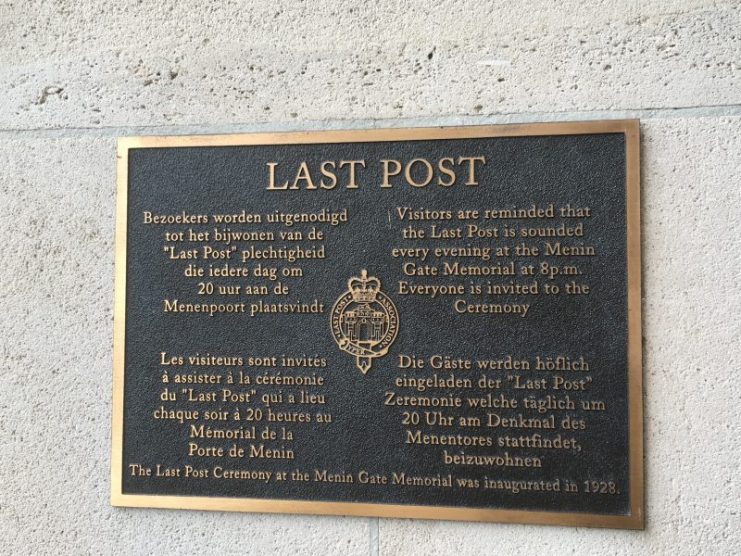

I remember a group of us running like hell, like a barrage was coming in, to a set meeting point. Running through the cobbled streets, because at 19:45 Hrs we had to meet our teachers at some gate. 19:45 Hrs?We were late!

We had barely enough time to get there before our teachers would have gone spare and dished out detentions for the following week. I remember one of the bigger lads asking a Belgian police officer the directions to the gate while we all stared in wonder at the gun on his hip.

And, so it was, at precisely 19:45 hrs Class 4B turned onto the Menenstraat, covered in mud, blood and maybe the odd tear. With the police officer at the head we were being led—no, marched—toward the Menin road, like so many before us. And there, for the first time ever, my eyes became fixed on a monument that I was in absolute awe of, The Menin Gate.

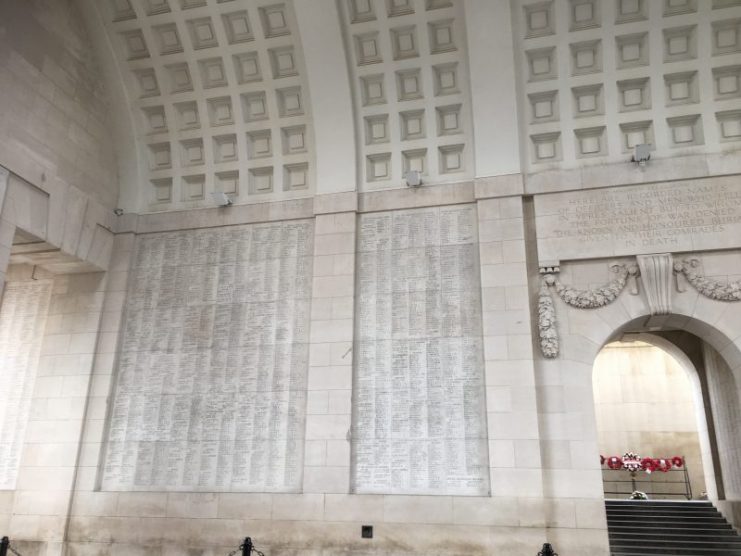

A memorial to over 54,000 missing souls. A memorial that overwhelmed me and scared me more than the glares of our form masters.

I had been struck by something I couldn’t at first explain. I was ashamed. I had been taken to Ypres to learn, to pay my respects, to read about sacrifice and to be grateful to a generation who, at that time, still lived amongst us. We had laughed and danced on the battlefields themselves without a care and now, as I stood under the thousands and thousands of names, I had so many ghosts looking down and judging me.

I remember wondering that if these men were to appear now, if they were to somehow change from their chiseled names to apparitions, what would they do?

I looked down at my ruined muddy shoes and a hole in my trousers and I remember the foolhardy things we’d done that day. Then I recall being snapped back to reality by a bugle. It was like being on trial for a crime. What WOULD they think of me?

I looked back at the wall of names and then, in the corner of my eye I remember seeing a man wearing a blazer with a handful of medals on his chest seated in a wheelchair.

I wish I could remember those medals. I often wonder whether he was British, Canadian or Australian. Was he a local Belgian war veteran? Was he German? So many men fought and died in this area that he could have been from any one of about 15 different countries. Was he an invalid from the Great War itself or was it simply through old age?

It wasn’t important then and I’ve learned to realize it’s not important now. What was important was that he was looking at me but he wasn’t angry or cross. He was smiling. He smiled at me and gave me a wink. He smiled as if to say “it’s ok lad. It’s ok to run around and be boys because that’s what these men fought for.”

They fought for a freedom and for a generation not yet born. They fought lads not much older than we were and they, only lads themselves, fought with the belief that we would never have to.

They wished that generation after generation would never have to pick up a rifle again. How wrong they were to be.

Over 30 years later I find myself standing under the Menin Gate again. Of course, the names are still there in their thousands. The crowds are still there, only much bigger, and of course, the school children are still there. The only thing sadly missing is the WWI veterans, long since gone to meet their friends who never had the life they did.

Read another story from us: Gas Gas Gas! Its First Ever Use – Ypres 1915

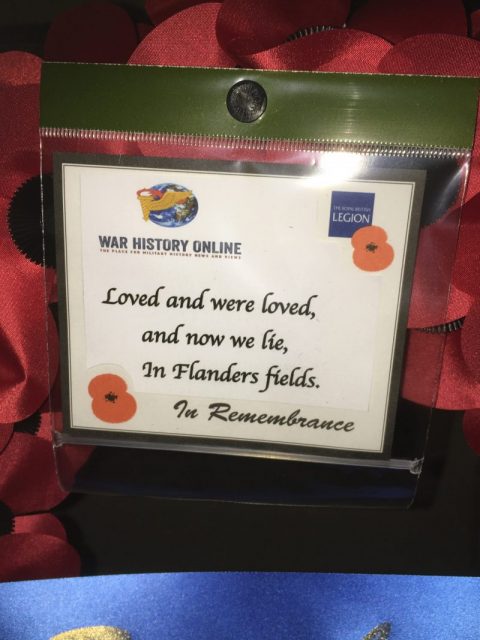

As the bugle finishes playing, I take one of the biggest steps of my life. I walk into the road and carrying the red wreath made of poppies I walk into silence.

I hope they remembered me as the boy covered in mud as I remembered them and the sacrifice they made.