The Battle of Chipyong-ni has been labeled as ‘the Gettysburg of the Korean War’ and has been singled out as one of the greatest regimental defensive actions in military history.

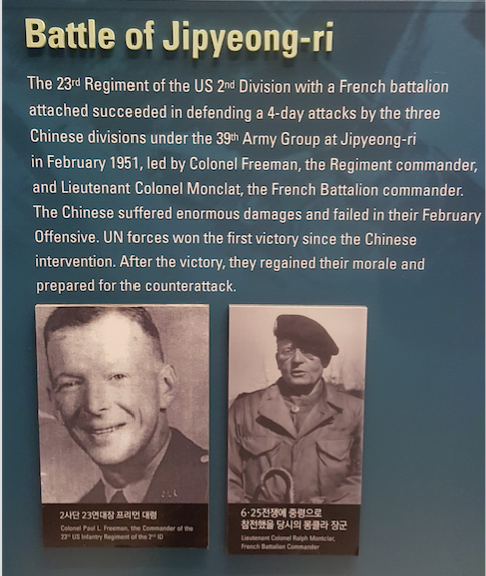

In a crossroads village that had already been reduced to rubble, American and French units of the US 23rd Infantry Regiment held off a ferocious and determined attack from the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army (PVA).

The failure of the communist forces to break through the 23rd’s defensive line would lead to a high-water mark being established in Korea.

Just days before the historic engagement, the regiment had been ordered to seek and eliminate the Chinese – which resulted in the Battle of the Twin Tunnels.

During two days of brutal, bloody, and exhausting work the PVA forces were defeated, but it came at a cost. The 23rd was reduced to 70% effective when they began the march towards Chipyong-ni.

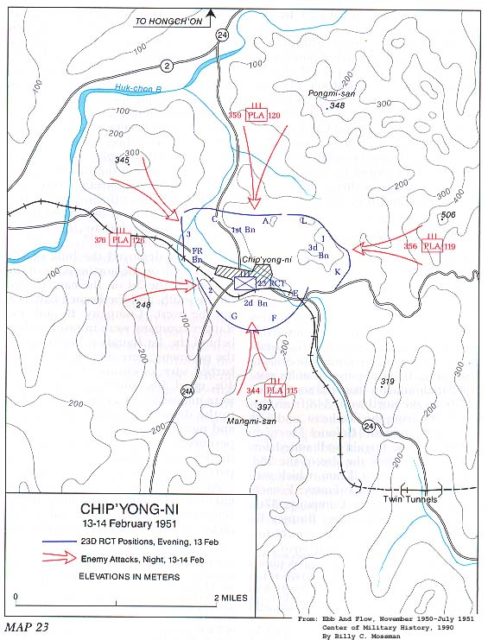

When they arrived there the commander, Paul L. Freeman, Jr. realized that his force of 4,500 men could not hope to effectively man the hills around the village, so he ordered the men to install a perimeter around the lower ridges that surrounded Chipyong-ni.

Interestingly, the French units that formed part of the 23rd were commanded by Raoul Monclar, who had given up his generalship so that he could be a battalion commander and stay on the front line.

As friendly units began to dig in they were reinforced by artillery, engineer and tank units. By the time the Chinese were ready to move against the 23rd, they had under their flag the French Infantry Battalion and First Ranger Company (both were attached to the regiment).

After the PVA attack against the X Corps at Wonju had effectively left Chipyong-ni behind enemy lines, they through the whole 39th Army as well as divisions from the 40th and 42nd to surround and destroy the US forces.

The exact size of the force that lined up against the 23rd during the battle is unclear. Some sources put the attacking numbers as high as 25,000 – while the Chinese claim they only threw 8,000 men into the fight.

But despite the heroics that Freeman’s men performed, it could have been so much different had his request to withdraw been granted. Instead, they built up their defensive positions and rained down merry hell on the attacking units.

The defensive line was then consolidated further as the commander began to undertake the work that would eventually repel the Chinese aggressors.

When you consider that the communist forces had the American and French troops surrounded at the Battle of Chipyong-ni, it makes their heroic and stoic defense of the village even more remarkable – and that’s exactly what happened as light faded on the 13th of February.

According to Ansil Walker, who wrote an account of the battle in Military History magazine, the 23rd were hated by the Chinese because they “had bloodied their noses previously at Kunu-ri during the winter retreat in North Korea and at Twin Tunnels a few days before.”

Any daytime advance was stopped short by the defender’s expert use of artillery, but it would only provide momentary respite as the enemy began to prepare a nighttime attack on the defenses.

They launched their first assault between the hours of 22:00 and 23:00 as the Chinese opened up with small arms and mortar fire at the American positions in the southeast, north, and northwest.

The defensive was as aggressive and brutal as the assault. E and G companies were tasked with the defense of Hill 397 and one tactic they used was detonate fougasse drums, which were 50-gallon drums half filled with gasoline and oil. As attackers got close to the drums, the men defending the positions detonated grenades underneath them – spraying the Chinese with a deadly mixture.

As the battle continued into the early hours of the morning the fighting was fiercest against K company, who were stationed in the east. In fact, it was so bad that no ambulances could get to the front line in order to evacuate the wounded men.

Towards the end of the night’s fighting, G company was in danger of being overrun and so tank support was dispatched towards the area.

Finally, at 7:30am the Chinese withdrew. They hadn’t managed to break through the line after a night of fierce fighting in near-zero conditions. A dusting of snow covered the communist dead in front of American lines.

It was Valentine’s Day, but there was no love in the air.

Freeman had been wounded during the night and the defenders had suffered about 100 casualties. Much needed air support kept the attackers away from the perimeter during the day, but the American and French units were running out of ammunition and another attack was coming.

They came at midnight, striking A Company before hitting C Company and the 1st Company from the French forces. It wasn’t long before the whole defensive line was under siege again while cargo planes dropped parachute flares which illuminated the battlefield.

Despite their best efforts, I Company could not prevent the Chinese from breaking through their lines at around 2:30. But a swift counter by men from I Company, L Company and machine gunners from M Company quickly restored the line.

However, the most serious threat of the battle came when the attackers broke through the perimeter just after 3:00am towards the south. The defenders were forced away from their positions and Freeman had to order the Rangers, an F Company platoon and some men from G Company to counterattack.

This failed and they were driven back by the Chinese some hours later. As a last resort, four tanks were sent out to flank the communist forces.

By the afternoon the Chinese made their retreat due to pressure from an Air Force napalm attack and a valiant assault from B Company, who lost 50% of their men in the action. The Americans and French lost 51 men and had 250 wounded. The communists lost 1,000 and had a further 2,000 wounded.