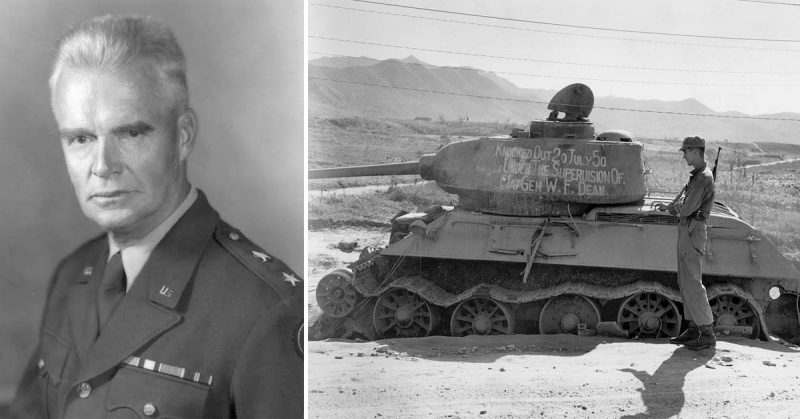

Early on after the start of the Korean War, it became clear that superior North Korean numbers and ill-prepared South Korea defenders would mean a brutal start for the American forces in the war. As the Americans mustered divisions for the war effort, the daunting task of buying time fell to Major General William Dean of the 24th Infantry Division.

Expectations that he could hold the defense against such numbers were low and his task was to simply delay the daunting North Korean advance at all costs. He would do so and the cost would be heavy both for himself and the men of the 24th. When they were completely overrun in the South Korean city of Taejon, he figured there wasn’t much General work to be done so he went out hunting North Korean tanks through the streets with small bands of soldiers.

During the subsequent escape towards American lines, the General would become separated from his men and spent the next 36 days wandering through the Korean wilderness alone before being betrayed by two South Koreas and turned in. He would spend the next 2 years in captivity and upon his release discovered he had been awarded the Medal of Honor while still listed as missing in action.

To the day he died, Major General Deans said he doesn’t deserve the Medal of Honor, but we will tell the story and let you be the judge of that.

First Responders of the Korean War

William Dean was born in 1899 Carlyle, Illinois and by the time the Korean War rolled around he was already an accomplished General with a strong resume. By 1950, he would find himself commanding the 24th Infantry Division based in Kokura, Japan.

This location would mean his men were in the closest proximity to respond to the North Korean aggression and the task of leading the first men to respond fell to him. The Division was severely understaffed and despite the recent World War, less than 15% of the men in the 24th Infantry Division had experienced combat.

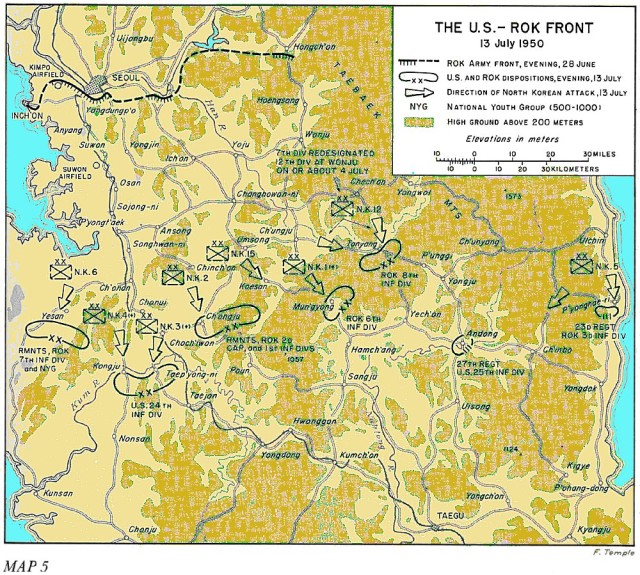

By the middle of July 1950, the North Korean juggernaut was rolling steadily south and for Major General Dean the seminal moment of his career would occur around the city of Taejon well south of Seoul. Dean had established the division headquarters here and was given explicit orders to hold the city until July 20th in order to allow the final completion of defenses around the Pusan Perimeter that would be the American and South Koreans last stand.

However, by July 19th multiple North Korean divisions were pushing Dean’s ability to hold to that deadline as they swarmed into the city.

Escape from Taejon

North Koreans began pouring into the streets, and it became a bitter house to house street battle for every block. By midday of July 20th, the North Koreans had nearly surrounded the city and efforts to evacuate the final American elements from the city were underway.

As the North Korean T-34 tanks roamed throughout the streets, it was at this point that Maj. General Dean decided he could be more useful as a grunt hunting tanks than a General staring at a map. He banded together with other small groups of men and began hunting tanks throughout the streets as they crawled from house to house.

At one point, General Dean is credited with an official confirmed tank kill by his own hand.

Having met the July 20th mandate, the time for all to leave was now and Dean remained behind to ensure the orderly withdrawal while the rest of the HQ headed out. As he departed in the final convoy during the hasty retreat, Dean’s Jeep had taken a wrong turn and became separated from the main group.

They eventually linked up with a separate group of American heading south moving primarily at night to avoid detection. When the group ran out of water, Dean went searching for a water source and fell down a ravine doing so only to be knocked unconscious while suffering a broken shoulder.

With the rest of the group unable to find the General in the middle of the night, they presumed him dead and headed out to reach American lines. By July 23rd the group had made it safely, but General Dean was still unaccounted for.

From Captivity to Hero

As Dean awoke to his injuries and the realization that he now lay alone behind enemy lines, he now faced the daunting task of reaching the American lines alone. At one point, he did briefly travel with another American soldier he ran across, but that soldier was later captured when they had to split up to escape near capture.

For most of the next 36 days, Major General Dean would roam the Korean countryside alone in pursuit of American lines. He ate whatever meager food he could come across to include meager handouts from friendly South Koreans, but lost over 60 pounds during this month-long trek.

Just as it seemed he was near salvation, two Koreans who posed as friendly turned him into the North Koreans on August 25th. Initially, the North Koreas were unaware they had a Major General in captivity but once it was known, Dean was sent to a separate camp where he would endure constant interrogation for the high-level information they presumed him to have.

He never broke to interrogation and even attempted suicide at one point when he considered he might. As far as the Americans were concerned, they had him listed as missing in action and presumed dead. Although he was captured in August of 1950, it would be over a year before the North Koreas would confirm his presence as the General was kept in isolation from other POWs.

In January of 1951, the missing Dean would be awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions outside of Taejon, which was given to his wife at a White House Ceremony.

However, the truth of his captivity would eventually become known, and Dean would become free during a prisoner exchange at the end of the conflict in 1953 and was welcomed home a hero.

But don’t tell that to Dean because this humble spirit would insist he did nothing special and to the day he died he claimed he didn’t deserve the Medal of Honor. However, gallantly leading men in an action to delay a numerically overwhelming enemy, personally hunting tanks as a General, and remaining behind to see to the orderly withdrawal didn’t seem like too shabby of a resume.

Then, when you consider his actions to return to American lines while isolated and alone along with his steadfast resolve as a POW, one could make a pretty strong case that he was, in fact, deserving of the nation’s highest military honor.