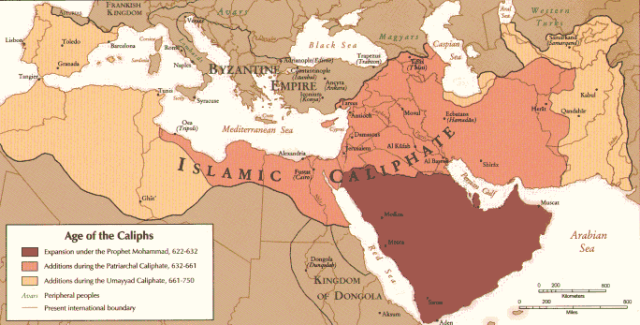

Few Empires emerged as quickly as that of the Muslim Caliphates. Bursting out from what is now Saudi Arabia in the mid-7th century, the Islamic Caliphate expanded outward in all directions.

Early on they won a crushing victory over the long established Byzantine Empire at the Battle of Yarmouk and swept westward across northern Africa. Eventually, they would cross the Strait of Gibraltar, defeat the Visigoths and seize Spain.

The Muslim conquests were not inherently about religion, especially seeing as the conquerors allowed freedom of religion in conquered territories, but their presence and culture was a direct threat to Western Christianity.

Similar to how the Vikings targeted churches for loot, so did the conquering Muslims. Furthermore, over time many of the people conquered by the Muslims adopted their religion.

The Muslims in Spain began threatening modern day France, by the early 8th century.

Spain had been under the rule of the Visigoths, the descendants of the men who sacked Rome, but they were unable to put up much of a fight and the Islamic Caliphate had no setbacks until they met Odo of Aquitaine. He won a victory at the Battle of Toulouse that temporarily halted the previously unstoppable force, and is sometimes held up as being equally important as the later battle of Tours.

Though Toulouse was a setback for the Muslim conquest of France, they would still conduct raids for the next decade. While the Muslims focused on raids, Charles Martel focused on building an army to unify and strengthen the Frankish people.

Odo of Aquitaine had recently suffered defeats and pleaded to Charles for help against the invading Muslims. Charles agreed to the stipulation that Odo submit to Frankish authority. A Frankish power was growing steadily stronger under Charles, and the Caliphate had no real idea of what they would find when they decided to venture north with a stronger army.

The Franks and The Muslims under the Umayyad Caliphate would meet in northeastern France in October of 732. Charles Martel, commander of the Franks, who were largely infantry based, and likely equal in number to the Muslim army, would fight General Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi, who commanded the Umayyad army that had a large amount of cavalry.

Charles’ force was well trained and fought with the equipment and close order style that echoed the hoplite formations of the ancient Greeks. He occupied an elevated position and used the trees and rough terrain in front of his infantry to protect them from cavalry charges.

Continues on page two

The first several days resulted in several skirmishes with no clear winner. Charles had adopted a defensive position while Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi was quite frankly (pun intended) surprised by the presence of such a large force.

Reinforcements arrived for the Muslims, but Charles had arguably better reinforcements. Many of his veterans, who had personally fought under him came in huge numbers. These professional fighting men would have been amongst the best and most experienced in all Europe. Their arrival meant that the main battle was at hand after a week of skirmishing.

The Muslims had a tried and true method of wearing down the enemy with light cavalry peppering and repeated heavy cavalry charges. With no real reason to try something different, ‘Abd-al-Raḥmân’s cavalry crashed into the Frankish formations who stood firm like “A Bulwark of Ice” according to later Muslim accounts. Frankish troops withstood the attacks and lashed out hard whenever the experienced troops saw an opportunity.

Deep into the fighting (perhaps into a second day according to some sources) The cavalry broke into a Frankish formation and towards Charles. His guard, and perhaps Charles himself, entered the fray. Several Frankish scouts were sent at the same time to raid the enemy camp, causing havoc and freeing prisoners.

The Muslims feared for the safety of their booty, obtained during the campaign and many rushed back to the camp. This was seen as a full retreat by many other members of the Muslim army and an actual full retreat soon followed. ‘Abd-al-Raḥmân valiantly attempted to rally his troops but was killed in the fighting as the victorious Franks swarmed upon their retreating foes.

The degree to which the Muslims were defeated can be inferred by the following events. The survivors retreated to their camp where they fled in the middle of the night, carrying mostly their prized loot. The next morning, Charles was deeply concerned that his enemies were setting up an ambush, trying to get him to march downhill to more open fields.

After extensive scouting, it was discovered that the enemy had fled. This would point to the battle surely being a great victory, but not a crushing one as Charles still had to fear a possible ambush. Also, most casualties in battle come after one side starts to retreat, but in this case, it was a victorious infantry army chasing down a largely cavalry based army, so there were likely plenty of Muslim survivors.

Estimates are that the Muslims lost around 8-10,000 compared to roughly 1,000 for the Franks. Though not a crushing victory it was a definite turning point for the push of Islam into Europe. The battle was unequivocally lost, and a great general was lost by the Ummayids.

They had become overextended and would eventually be forced to withdraw back into Spain. Charles was granted the nickname of Charles “the Hammer” for crushing his enemies and both he and Odo, who had won the first great victory and served at Tours, would be considered heroes of Christianity.

Charles would go on to establish the Frankish kingdom, and his family line would produce such greats as Charlemagne.