The Hundred Years War (1337-1453) saw the first appearances of gunpowder artillery in English and French warfare. These fearsome weapons, which had been largely unused in the conflicts of Western Europe, were deployed in sieges and on battlefields by both sides.

Though not transformative, their presence was significant, making this war an important stage in the development of artillery.

Early Guns

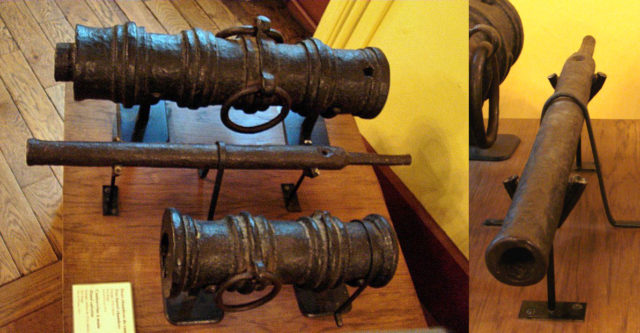

Though gunpowder had existed for a long time in East Asia, it only arrived in Europe in the 13th century. There it was combined with Europe’s relatively advanced metal casting skills to create cannons that channeled powerful black powder blasts, launching large projectiles with great force.

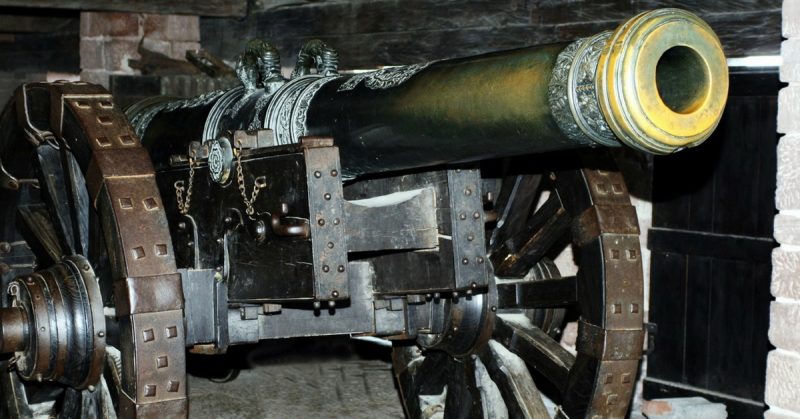

The English adopted cannons during the reign of Edward III. We see the first illustration of one of these weapons in a manuscript prepared for the young Edward by his tutor, Walter de Milemete. In 1333 we have the first reference to these weapons in action at the siege of Berwick. But it was with Edward’s expedition to France in 1346 that they first became significant. There he fielded his cannons at the Battle of Crécy and deployed them to bombard Calais during the siege of that vital port.

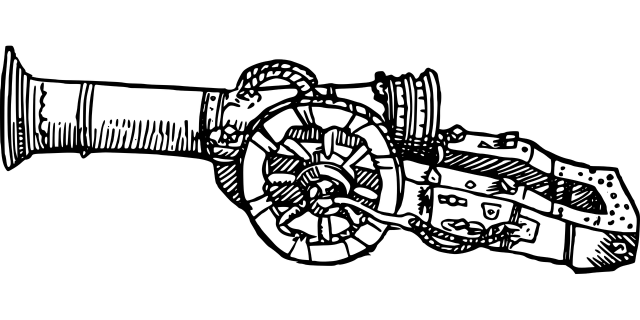

What followed was not the immediate adoption of cannon as we know them. Some of these weapons would look odd to a modern observer – the illustration in Edward’s manuscript showed a vase-shaped gun firing a large arrow. Though their use soon increased, they were fielded alongside older siege weapons for a generation. But guns were now in the field, and would remain important throughout the Hundred Years War.

Cannon in Sieges

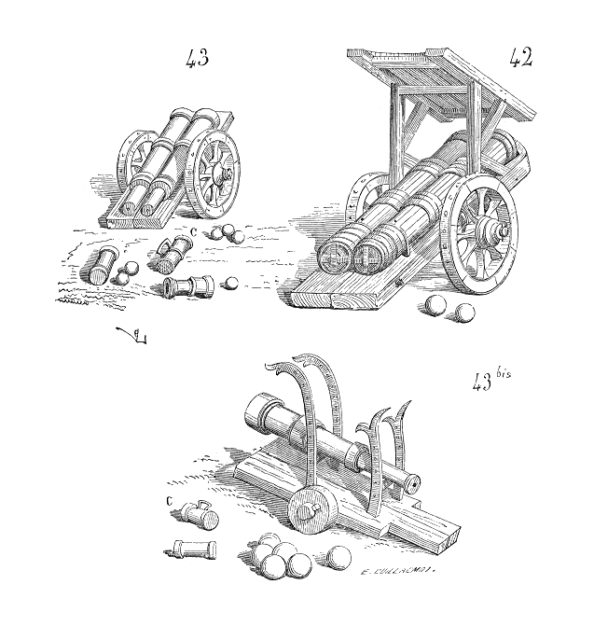

In 1375, French forces laid siege to Saint-Sauveur-le-Vicomte, and for the first time they fielded a large battery of cannons. Having been on the receiving end of English firepower thirty years before, the French monarchy had quickly grasped the importance of these weapons and set about acquiring its own. Thirty-two cannons were deployed before the walls of the town, with ammunition being brought in along the dirt roads, packhorses and carts straining beneath sacks of stone balls.

Transporting large numbers of cannon and piles of ammunition to the war zone was trickier for the English, but this didn’t stop them. Henry V used artillery to rain fear and destruction down on Harfleur in the siege of 1415. Two years later, the Brut chronicle referred to him bringing artillery fit for a king, such guns having become a sign of royal status. They were deployed in the successful captures of Caen, Falaise and later Rouen.

Part of the reason why cannons were so decisive in these sieges was that the fortified walls had been designed for an earlier era of siege craft. They were tall and thin to stop men getting over them. But this made them vulnerable to cannon shots, which could punch through these thin barriers. It was only as defensive architecture changed that they were able once again to provide protection against attacking artillery.

Cannon in Defence

This did not mean that towns and castles were suddenly defenseless thanks to the new technology. Cannons were taking time to develop, and the early models were far from their full potential. Their impact may have been as much psychological as physical, thanks to the shock of these loud, flame-belching weapons. Significantly, they could also be used in defense.

Just as besiegers could fire cannons at a town’s walls, the defenders could fire from those walls down upon exposed attackers. The earliest example of guns being incorporated into a town in England or France comes from Cambrai, where the defensive system incorporated guns as early as 1339 – before Edward III had demonstrated their fearsome attacking power. By 1378, they were being included in the defenses at Canterbury and Southampton, back in the relative safety of England.

By the early 15th century, the use of cannons in defense was considered not just normal but necessary. Towns and castles all over France had them. Gunpowder was stocked ready for emergencies, and many towns appointed an artillerist to oversee the effective use of the weapons in a siege.

Cannon on the Battlefield

It was easiest to use cannon during sieges. In these static confrontations, they could be set up in relative peace and kept in one spot without fear of being overrun by the enemy. Given their cumbersome bulk, great weight, and explosive ammunition, this was by far the safest and easiest way to use them. Taking them on the swift marching raids of the English, or the counter-manoeuvres of the French, would at times have been impossible.

This didn’t prevent them from playing a part in pitched battles. The celebrated English victory at Crecy featured the firing of cannon, which helped to put the fear of the English into the French soldiers and the Genoese mercenaries serving with them. At this early stage, many might not have heard the roar of a cannon in action before, giving them greater impact than they would have a few years later.

From beginning to end, the fast developing gunpowder weapons played a part in the Hundred Years War. In 1453 at Castillon, the final battle of the war, the French defeated the English, in part through the devastating impact of gunfire on the bodies of their advancing foes.

Changing Cannon and Shot

Cannons and ammunition changed greatly over the course of the war, which filled most of the first century and a half of their development. Carved stone balls and large arrows were replaced by cast metal cannonballs, which carried great forced without shattering on impact as the stone balls often did. Gun casting improved, allowing more powerful charges to be used without guns self-destructing from the force.

All of this played into the growing importance of central government in running armies. Expensive cannons could seldom be supplied in large numbers by anyone else. The growing importance of artillery added to the importance of national armed forces, with both far more significant at the end of the war than its start.

Source:

- Christopher Allmand (1989), The Hundred Years War: England and France at War c.1300 – c.1450.

- William Weir (2006), 50 Weapons that Changed Warfare.