Beneath the relentless beating of the midday sun, under a seemingly endless rain of arrows, The Grand Master’s patience had all but run out.

Garnier de Nablus, the leader of the Knights Hospitaller, had pleaded with the King, but to no avail. He had begged him to sound the horn and begin the attack, to finally turn the tide against the enemy that had antagonised them all the way along the coastline.

Richard, I earned in his lifetime the title Lionheart, but on this bright September morning, he had stolidly refused to live up to that particular name. Instead, even as the enemy relentlessly harassed his forces, he exercised one virtue above all others; patience.

Again and again, Saladin’s mounted archers would rush from the trees, launching deadly volleys into the column of armoured and dreadfully fatigued men below. Then, even as the Crusader troops attempted to return fire, the horsemen would turn and vanish into the trees once more.

At first, their efforts had been spread up and down the length of the line, but the Lionheart, insisting that his men maintain their positions, seemed unmoved. The day dragged on, and, in time, Saladin began to concentrate his forces on the army’s rear. The Hospitaller knights who marched at the end of the line soon found themselves under an increasingly intense assault.

Before long, the knights were walking backwards, holding their shields up against a barrage of arrows and javelins. Some of the men were able to maintain a fairly robust defence using their crossbows, but the situation was rapidly worsening.

Yet still, King Richard did not give the order to retaliate.

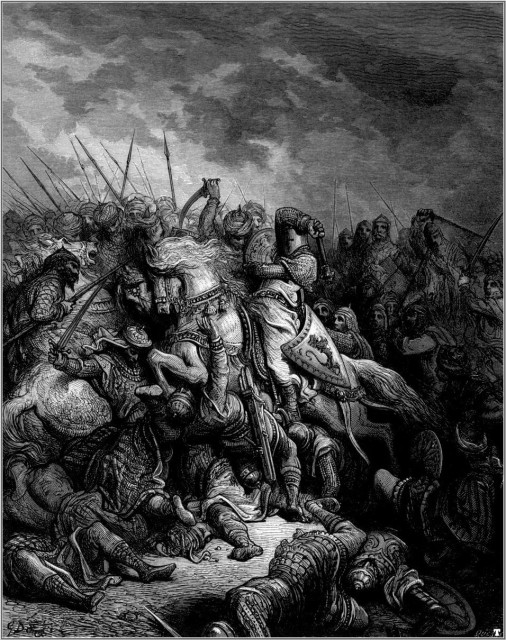

It was obvious even to the Grand Master that his own desire to break ranks and give chase was exactly what Saladin was hoping to provoke. However, his men soon had more to contend with than just archers; a large portion of the enemy’s right flank closed in around them, led by the Sultan himself. Saladin had joined the fray, riding into battle and pushing the Hospitaller forces to near breaking point.

Suddenly, as the line of crossbowmen paused to reload their weapons, the enemy broke through their ranks. The Hospitallers were exhausted, thirsty and demoralised; faced with little resistance, Saladin’s forces drove deeper into the column, dealing death on every side. Seeing for himself the carnage at the rear of the army, Nablus rushed to the King, begging once more for the order to attack.

“My lord king!” he cried. “We are violently pressed by the enemy, and yet we are to be remembered in infamy, for we did not dare return their blows. Why should we bear these attacks a moment longer?”

“Good Master,” replied the King, shaking his head with hardened eyes, “You must weather this attack. The time for an assault will come soon enough, but for now, I would have you return to your men and sustain the line.”

Thus, once again, Richard had refused him. A counter-attack was exactly what the Sultan wanted, and the signal to charge – six short horn blasts – would not be heard until the time was right.

It was then, as the afternoon wore on and the enemy pressed ever harder against them, that Nablus made a sudden decision. That choice could have meant death and treason – for him and for his men – but he knew with a certainty what had to be done. Mounting his horse alongside Baldwin de Carreo, a friend and fellow Hospitaller, the Grand Master drew his sword and roared,“St George! St George!”

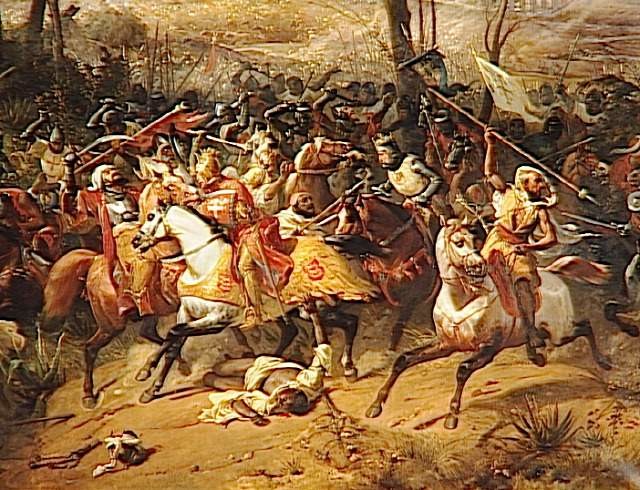

A moment later he was moving, breaking through his own ranks and charging towards the enemy infantry head-on. Behind him, the Hospitaller knights who formed the rear defence took up the same cry and began to surge forward, following their leader into battle.

For a moment in seemed as though they might fight alone, but further, up the line another large company of French knights saw the charge and drew their own weapons. Refusing to stand by as the Hospitallers rode into battle, they turned their mounts around and rallied to the Grand Master’s call.

At the head of the column, word reached King Richard that Nablus had defied him. Once more, a difficult choice had to be made. The vanguard had already reached the walls of Arsuf, but the rear was quickly disintegrating. There was little time to pause and think, to weigh up his options; without wasting another moment, the Lionheart gave his order.

“Sound the horn,” he shouted.

In the hot afternoon ai,r the clear call of the horn was heard six times. It cut through the cacophony of the battle, and Nablus knew then that he had not led his men to certain death. Had his King decided to retreat into Arsuf, abandoning the Hospitallers to Saladin and his men, there would have been no hope. Yet now, as the horn sounded, his heart leapt.

Behind him, the Crusader infantry began to open the ranks, creating passages within their numbers through which lines mounted knights could pass. In a remarkably short space of time, Richard’s relentlessly passive army had changed its strategy entirely – now they were rushing in full force to engage with Saladin’s troops.

King Richard himself, not to be outdone even by the Sultan, mounted his steed and rode down the column. At last, with the full might of the Crusader army at this back, he led his men against the enemy that had preyed upon their flanks for so long.

The soldiers who had been attacking the Hospitallers only a short while earlier were caught in tightly-packed formations. With no time to spread themselves out, they were forced to face the full impact of the Crusader charge where they stood; it took very little time for a rout to begin. The Lionheart was in the centre of the battle, cutting down any man within his reach, and by the end of the day, his army had achieved a resounding victory.

In the end, the decision by Nablus to ignore the King’s orders paved the way to their triumph, and on that day at least the forces of Saladin retreated in chaotic defeat. Though his actions flew in the face of Richard’s direct command, the sun may well have set on a very different battlefield had Nablus made the wrong choice. It seems quite clear that the Hospitaller’s reckless and heroic charge was a decisive factor in the Battle of Arsuf.