The supremacy of heavy cavalry and mounted knights on the battlefield came to an end one cold November morning in 1315, and it began with a single arrow – a single arrow and a note.

The letter had been lashed to the shaft with coarse twine, and the arrow shot from the rocky bluff above the Swiss camp. At the bottom of the page, the signature of one Henry Huenenberg was printed in black ink.

Perhaps the Austrian knight was of a remarkably chivalrous disposition, or perhaps the prospect of crushing an army as small as the Swiss Confederates’ was beneath him. Whatever his motivation, Sir Henry chose to deliver a message to his enemies – go home, the letter urged, you cannot win this battle and you cannot win this war.

Along with this advice, the knight included the date upon which the Austrian army would march on Morgarten Pass – November 15th. If the soldiers of the Confederacy had not dispersed to their homes by then, they could expect no mercy from Leopold I, the Austrian duke to which Huenenberg swore fealty.

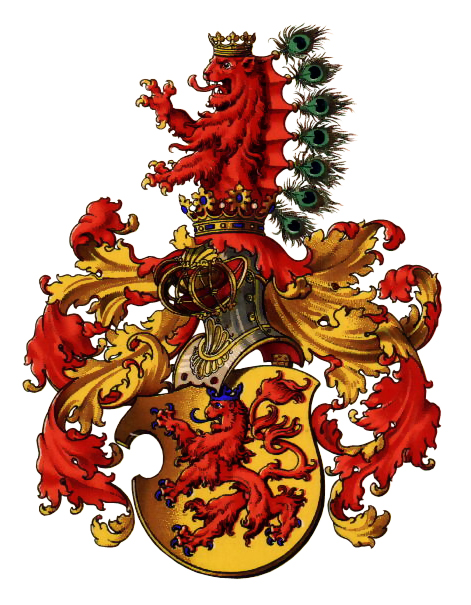

In the months following the raid on Einsiedeln Abbey – a catalytic event that turned rising political tensions into open warfare – the conflict between the House of Habsburg and the Swiss Confederacy had rapidly escalated. With multiple claims being made to the crown of the Holy Roman Empire and a myriad of factions battling for control of the coveted Gotthard Pass, Europe was in turmoil.

Now – as the winter of 1315 set in – a small militia, fighting for the Swiss Confederacy, had massed to hold back the Austrian troops. Vastly outnumbered, they were facing a military force with superior training and far better equipment. The Duke had in his army a powerful contingent of heavy cavalry, including many of his best knights. Against him, the chances of victory for the Swiss infantry seemed very slight indeed.

In fact, when the sun rose on November 15th, the Austrian army found the way before them deserted. Towards the Morgarten Pass marched a force of 9,000 men, many of them seasoned knights; was it any wonder that the Confederate militia had melted away in the face of such a threat?

To their right the lake stretched out, water glittering the in light of a bright winter sun. On the other side of the column, a steep slope rose to a wooded summit high above. The morning was clear and cold; steam rose from the mouths of the knights and the nostrils of their horses as they progressed steadily along the road.

Then, quite suddenly, the vanguard of the Austrian army came to a halt.

There, rising across the path in front of them, was a crudely constructed barricade. The wall had been raised with logs and boulders and reinforced with heavy staves on the farther side. It would take some time to dismantle it, but there seemed no other choice.

Further down the line, however, word of the barricade was yet to reach the main body of the Austrian army. Without even knowing that the men at the front of the column had come to a halt, the infantry continued to march forward, until the majority of the troops were crammed into a chaotic bottleneck between the wooded slopes and the water.

Then something moved among the trees.

Most of the officers below were busy trying to order the infantry behind them into lines or passing word back to the rear to stop advancing. It wasn’t until the first stones began to fall that the army on the road below looked up at the hill to their left.

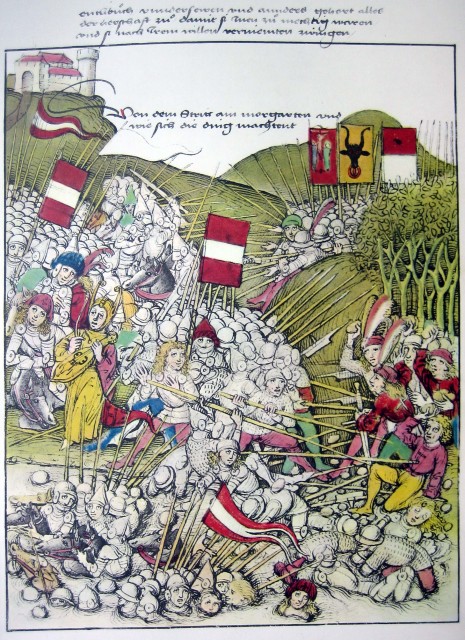

Out of the trees, they came, rushing into the open as the sunlight flashed across their halberds. The Swiss Confederates were sounding horns, hurling stones and logs, loosing one volley of arrows after another. Below them, the chaos could only escalate.

The Austrian Duke realized what was happening at once. He had led his men into a trap, and with the lake at their backs and the enemy swarming across the higher ground, he had to act quickly. He tried to rally his knights, but moving a horse even a small distance was almost impossible in the throng of bodies that had gathered before the barricade. For the vanguard, there was simply nowhere to go.

A steady rain of projectiles beat down upon them. Where the arrows and stones failed to kill the Duke’s men outright, they served to fuel the fires of panic that was spreading rapidly through the larger Austrian army.

To the rear of the column, the foot soldiers and infantrymen who still had a chance to escape turned and ran, fleeing back down the road they way they had come. For the mounted knights still crammed against the barricade, retreat was no longer an option.

As the back of the army began to disintegrate, the Swiss militia charged.

Outnumbered they may have been, but they had used the landscape they knew so well as a weapon against their enemies. Moving quickly down the slope towards their prey, the Confederate soldiers levelled the halberds and plunged into the crumbling Austrian flank. The Duke’s knights, mounted and weighed down with heavy armour, had little hope of holding the line.

For the first time in the history of European warfare, heavy cavalry proved to be a liability rather than an advantage. The long Swiss halberd could drive a man from his horse or even kill him in the saddle, even as the weapon’s bearer remained outside of a knights’ reach. This proved to be a defining factor in a battle that was quickly turning into a massacre.

On the other side of the road, with the water directly behind them, many of the Austrian men who had watched the decimation of their mounted knights turned and plunged into the lake. Even as they drowned, they could hear the sounds of their comrades’ dying screams upon the road.

Those who could still run routed and fled back along the path, only to be cut down from behind. The Austrian knights and mounted men-at-arms were slaughtered, officers showed no more mercy than the common infantrymen, and by the end of the day, the Duke’s army was no more.

The Battle of Morgarten proved to be a dramatic power shift within the history of mounted warfare, but it was even more than that. An army less than half the size of the well-trained Austrian forces had won a resounding victory against all the odds.

In the end, their lack of proper cavalry units became their greatest asset. This, combined with their knowledge of the landscape they were trying to defend, allowed the Swiss militia to prove unequivocally that no outcome is ever set in stone.