1066 is the most famous year in English history. Led by Duke William, the Normans conquered the country, forever changing its laws and culture. But there was another invasion first, the last in several centuries of Viking raids.

A Claim to the Crown

When King Hardicanute died in 1042, his Anglo-Danish kingdom came to an end. England was inherited by Edward the Confessor, while King Magnus I of Norway took Denmark. Magnus laid claim to the English throne but was unable to act on this before his death in 1047.

In January 1066, Edward the Confessor died without leaving a direct heir. The Witan, England’s great council of nobles, selected the Earl of Wessex, Harold Godwinson, to become king. Harold’s claim to the throne was a little tenuous, but he was the strongest native English candidate. He was also a powerful lord and an established leader.

Magnus I’s successor, Harald Hardrada, took the opportunity to revive his predecessor’s claim to the English throne. Tall and confident, a veteran who had traveled to and fought in distant lands, Harald was a strong leader. Seeing England weak, he intended to use that strength to expand his kingdom.

The Reavers Return

The trouble started in May when King Harold’s younger brother Tostig made a brief and ineffective invasion from France. Fleeing to Scotland after his defeat, he contacted Hardrada, offering to work with him.

Because of Tostig’s invasion and the threat of attack from Normandy, King Harold assembled his army in the south. The core of it was the house-carls, 3,000 elite soldiers armed with shields and two-handed axes. But the rest was the fyrd, a levy of free men who only had to serve for two months. When no invasion came, Harold had to disperse his army.

Meanwhile, Hardrada sailed from Norway via the Orkneys. Joined by Tostig, he landed in northeast England, sacked Scarborough, and traveled as far south as the mouth of the Humber.

For people living in northern England, it must have been a terrifying moment. An estimated 10,000 raiders arrived in at least 200 longships, a mixture of Norsemen, Flemings, Scots, and even some English troops. They sailed up the river Ouse, like the pillaging Vikings of past centuries.

The invaders disembarked at Riccall. Leaving some of his army to protect the boats, Hardrada marched the rest of his men ten miles north to York, through flat and swampy land.

Fulford

The Earls Morcar of Northumbria and Edwin of Mercia rallied their troops to defend against this invasion. There was no certainty that King Harold would come to the rescue, given the Norman threat to the south, and so the north would have to protect itself.

York’s defenses weren’t sturdy enough to hold off the attackers so Morcar and Edwin marched their troops out to face the Vikings in a pitched battle.

On the 20th of September, the two sides clashed at Fulford. Fought on wet, open ground, it became a grinding, protracted battle that lasted nearly all day.

At first, things went well for the English. They pushed forward on the left and seemed on the verge of winning there. Soon, the forces of the earls were heavily engaged in the center and on their left flank.

But Hardrada was a cunning and experienced commander. Now that his opponents were busy, he launched an attack on the other flank.

His men swung away from the river and around the edge of the English. They drove them back into a ditch, slaughtering those who stood against them while more drowned in the muddy water.

By the end of the day, Hardrada’s banner flew in triumph over the battlefield. The opposing army had been completely destroyed.

In the aftermath, the Norsemen retreated to their boats while Tostig and Hardrada negotiated York’s surrender. As part of this, the people of York agreed to hand hostages over to the Vikings. Arrangements were made for this to happen where four roads crossed the River Derwent, at Stamford Bridge.

Stamford Bridge

Meanwhile, King Harold had shown the decisiveness that made him a great leader. Assembling whatever soldiers he could, he marched north. As he went, more men gathered around him. The core of the army traveled 180 miles in just four days, a remarkable forced march.

Harold himself had been sick when he left London and the march must have exhausted his army. But he was not going to let this hold him back. Arriving at York early on the 25th of September, he learned that Hardrada and Tostig’s army was at Stamford Bridge, and so marched straight there.

A mile west of Stamford Bridge, the English army crossed a rise and came in sight of the invaders.

The Norsemen were caught completely by surprise. Most were on the far bank, their armor off so that they could enjoy the sunshine. They had no idea that another army was coming to fight them.

The English fell upon the few Norsemen on the west bank. Many died fighting. Others were driven into the Derwent and drowned.

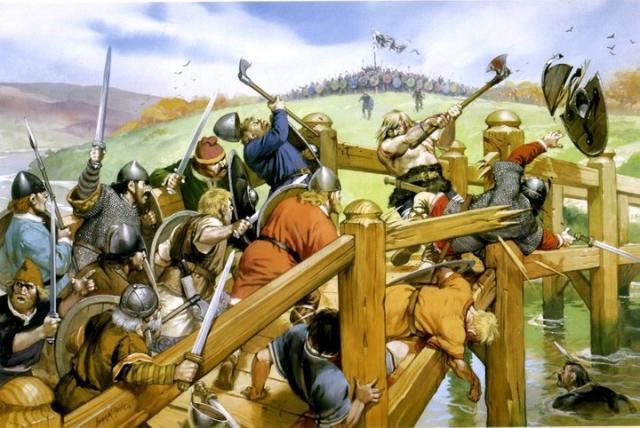

For a while, a single fearsome Norseman held the bridge. He stopped the English advance until a house-carl turned a swill-tub into an improvised boat, paddled under the bridge, and stabbed him with a spear from below.

Having crossed the river, the English faced a hastily assembled shield wall. It was another grueling fight, one that lasted for most of the afternoon, with the Vikings reforming their line whenever a gap appeared. At last, Hardrada was hit by a missile and died. Tostig lacked the authority to rally men made fearful by the loss of their king. The line collapsed and Tostig was among the many men who died.

King Harold was magnanimous in victory. He let Hardrada’s son and the surviving Norsemen sail home, then took his brother’s body and buried it at York.

The last great Viking invasion of England had been defeated. But there would be no peace for Harold and his weary army. Across the English Channel, the Normans were gathering. The English had won two victories. They would not be so lucky the third time.