Mel Gibson’s film Braveheart is both one of the most celebrated and one of the most reviled pieces of historical filmmaking ever. A heart-stirring and carefully crafted piece of story-telling, it won five Oscars. Yet the wild liberties it took with history have led it to be repeatedly panned by historians and critics.

This is especially in true in Scotland, where it has become almost a byword for historical inaccuracy. In spite of this, it is still widely enjoyed by Scots, and it is appreciated for placing the story of a Scottish hero, William Wallace, firmly in the cultural mainstream.

So what does Braveheart get wrong about the Anglo-Scottish wars in which William Wallace fought, and what, if anything, does it get right?

William Wallace, Peasant Leader

The central character of Braveheart is William Wallace. In the film, he’s shown as a man of humble background who goes to war after the love of his life is murdered by English invaders.

In reality, Wallace was part of the lesser Scottish nobility. His family was too obscure to leave detailed information about his origins, but we know enough to get a picture of his lifestyle. Far from being raised as a farmer, he was raised to be a minor noble, and trained in the arts of war from a young age.

Men of his standing lived off the rents paid by peasants for living on their lands, and by fighting. When a war came up, this meant serving under the lord above him. Case studies from northern England have shown how, in times of peace, these skills were often turned to banditry and local feuds.

As part of his education, he was sent to Rome for a time before returning to Scotland, and this is referenced in the movie.

Wallace was no peasant patriot. He was a member of a warrior aristocracy who excelled at the life he was given.

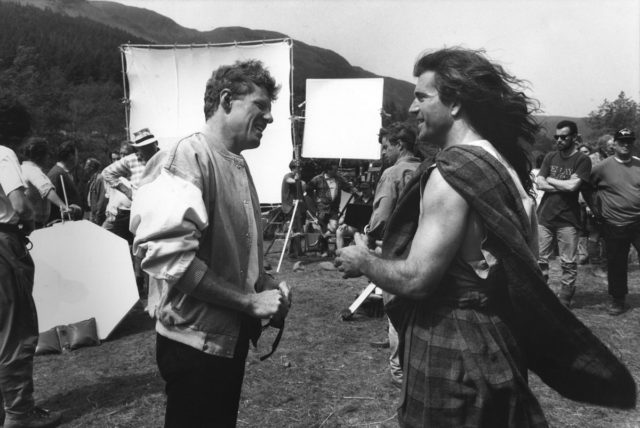

Stirling Bridge

The Battle of Stirling Bridge is one of the most important battles in Scottish history and the crowning glory of Wallace’s career. The bridge was absolutely vital. Strategically, it was the place where Wallace and his co-commander Andrew Moray could stop the English from getting further into Scotland, and so protect the vulnerable government. It also took place within view of the magnificent Stirling Castle, which was the seat of Scottish Kings for many years.

Making clever use of the bridge and a bottleneck of land beyond it, Wallace and Moray trapped the English, turning their numbers against them. A badly outmatched Scottish army defeated the English through cunning, bravery, and tactical use of that bridge.

Braveheart sets the Battle of Stirling Bridge in a field. No bridge. No cunning manoeuvre. None of the things that make the battle interesting or that proved Wallace’s intelligence as a commander, and no sign of Stirling Castle.

Where’s Moray?

Speaking of Andrew Moray, Braveheart entirely misses out this man, one of the most important in Wallace’s career. Up until the mortal injury he received at Stirling Bridge, Moray was as important a commander as Wallace.

The two men combined their outlaw armies, Wallace bringing greater numbers while the more aristocratic Moray brought greater prestige. Stirling Bridge was as much Moray’s victory as Wallace’s, yet he is forgotten here.

Capturing York

William Wallace raided northern England. Any Scottish commander worth their salt did, as this was how the two sides tried to wear each other down. What he never did – contrary to the film – was to besiege and capture York, the most important city in northern England.

Negotiating with Isabella

The film depicts Edward I sending his daughter-in-law Isabella to negotiate with Wallace. The two are attracted to each other and do what pretty people do in Hollywood movies, leading to Isabella becoming pregnant with the future King Edward III.

At the time of Wallace’s execution, Isabella was nine years old, living in France, and not yet married into the English royal family. So let’s just get angry about the inaccuracy of portraying her as a fully grown negotiator and not even think about the rest of what’s going on here.

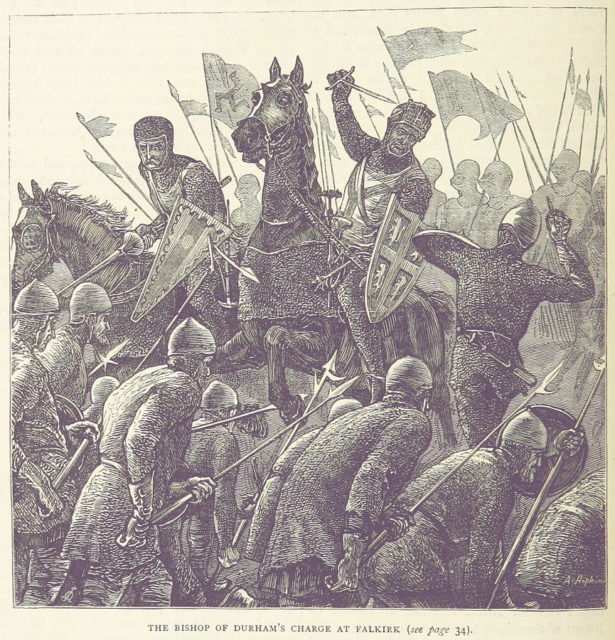

The Irish at Falkirk

We also get to see one of Wallace’s defeats – the Battle of Falkirk. Setting aside every other problem with the depiction of this battle, including the make-up of Edward I’s army, Irish troops are shown carrying a flag that wouldn’t be invented for another 340 years.

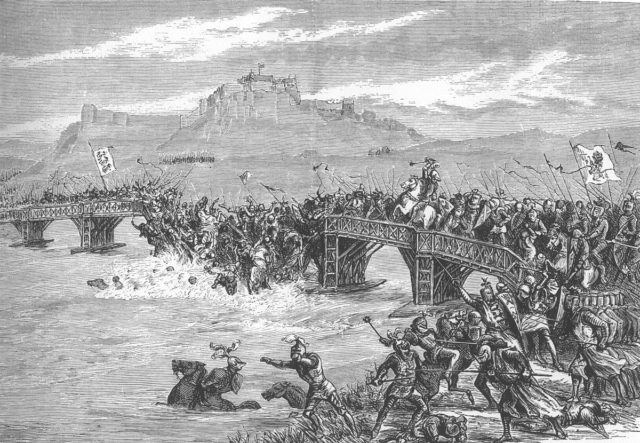

Woad and Tartan

In costuming its Scottish army, Braveheart veers wildly into both the past and the future. Scottish troops are seen wearing blue woad face paint – a habit of the ancient pre-roman Celts and Picts, not medieval Scots – and tartan kilts, a fashion that would only be invented hundreds of years later.

They look incredibly Scottish, to the modern eye, but not at all realistic.

Wallace’s Execution

There’s a lot to praise in the depiction of William Wallace’s execution, which shows the terrible brutality of medieval punishments. But there’s also a massive problem. Edward I is shown dying at the same time as Wallace.

In reality, he died two years later, not in his bed but on campaign, marching north to put down another Scottish rebellion.

Getting Robert Bruce Right

The only character to get a balanced and reasonably accurate portrayal in the film is Robert Bruce. The details are often implausible or clearly made up, but the general approach of the film captures the essence of Scotland’s greatest national hero, a man who would come to outshine Wallace.

From the start of the wars, the Bruce clan, and in particular Robert, shifted back and forth in their loyalties. Like many Scottish nobles, they bowed the knee to Edward I when resistance looked futile, and on one occasion to buy Wallace time.

Following Wallace’s death, Bruce murdered his competitor for the Scottish crown before becoming the leader of an outright rebellion. His shift to a fully anti-English position was as much pragmatic as patriotic, but he did become the leader Scotland needed.

Braveheart inaccurately portrays the heroism of William Wallace, the evil of Edward I, and a thousand other details. But in providing a complex picture of Robert Bruce, a man usually idealised in fiction, it brings something surprisingly accurate to the screen.

Mel Gibson’s Scottish Accent

Mel Gibson, a native of the US who has lived for a long time in Australia, worked hard to create an accurate-sounding Scottish accent as he played the lead role.

While it may sound about right to some, to the Scottish ear it leaves much to be desired and comes in for a great deal of mockery. In Mel Gibson’s later works which deal with older history, such as Apocalypto and The Passion of the Christ, much effort has been put in to recreate the ancient languages which would have been spoken at the time.

Maybe Mr. Gibson would consider a remake of Braveheart with this, and a certain bridge, in mind? One can only hope…