One of the strangest military formations ever seen in Europe, Hussite war wagons struck fear into their opponents during the early 15th century. Fighting under the leadership of Jan Zizka, they fought in the name of a priest who was already dead, pre-empted the wars of religious reformation by a hundred years, and ultimately became victims of their own success.

The Hussite Revolt

In the early 15th century, the bitter religious divisions that would create Protestantism were beginning to take shape. A century before Martin Luther would nail his theses to the church door in Wittenberg, a few brave men were calling for church reform. As the pressure mounted, the papacy fought back hard, and heretics started to be executed by burning.

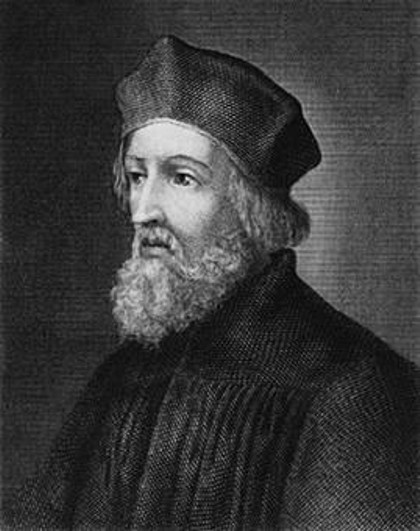

One of these dissidents was Jan Hus. A popular reformer, his burning in 1415 provoked outrage among his followers in Bohemia. Rising in revolt, they fought against the entangled spiritual and political authorities of their homeland. Their discipline and high morale led them to victory despite being equipped mostly with simple infantry weapons. In 1420 they expelled their king, Sigismund of Hungary.

Europe watched with bated breath to see what would happen next.

Jan Zizka – Veteran and General

The greatest leader of this revolt was a military veteran named Jan Zizka. Born into the gentry around 1378, he became a professional soldier. During his career, he had fought against the famed and dreaded Teutonic Knights at Tannenberg in 1410 and later lost an eye while in the service of King Wenceslas IV.

With one eye missing and carrying the Hussite symbol of the communion chalice on his shield, Zizka was a powerful image of the revolt.

He was also a gifted commander, swift in strategic movement and smart at choosing good defensive sites to fight on.

The War Wagons

Aside from Zizka’s leadership, the greatest weapon in the Hussite arsenal was the war wagon.

Hussite armies took war wagons with them wherever they went. Protected by hoardings and planks, bound together with iron, these hardened wagons were circled before battle. The horses were unhitched and the wheels interlocked, forming a fort on any battlefield where the Hussites chose to fight. Missile weapons could be fired through gaps in the wagons’ sides, and artillery placed between the wagons.

Each cart contained men with long flails ready to fend off attackers, as well as missile troops who turned the static formation into a battlefield threat. An infantry strike force and smaller cavalry groups sat safely inside the ring, ready to storm out once the enemy became disordered.

Fighting Off a Crusade

The wagon forts were like nothing the Hussites’ opponents had ever faced. They gave the Rebels their first victory in the face of superior Royalist forces at Sudomer on 25 March 1420.

A crusade was called against the Hussites, and Sigismund led crusading forces back into his kingdom. On 14 July he attacked the entrenched Hussites at Prague and was driven back. As Sigismund retreated, the Hussites captured royalist castles.

Sigismund returned in 1421 but was again defeated by Zizka, this time at Kutná Hora in December. By now Zizka was completely blind, having lost the sight in his remaining eye at the siege of Rabi, but he was as capable as ever. As Sigismund withdrew, the Hussites pursued, catching up with his rearguard at Habry and routing them.

Its momentum lost, the crusade dispersed. Sigismund was on the ropes.

The Victors Fight for Control

The Hussites had set up a council to run the country. Consisting of twenty regents from the cities and the nobility, it worked while the rebels were under pressure. But divisions started to emerge, with the nobility gathering under the banner of the Utraquist moderates and threatening to defect to Sigismund.

Prince Korybut, a nephew of the grand duke of Lithuania, tried to use the opportunity to gain the Bohemian throne. A series of battles followed, ending in a negotiated settlement in 1424. Uniting the various factions, Zizka led them on a campaign into Moravia. It was during this expedition that he died at the siege of Pribyslav. Without his leadership, the army abandoned the campaign.

The Hussites on the Offensive

Over the next few years, further crusades were launched against the Hussites. Led by a priest named Prokop, the Hussites drove back the crusaders in 1426 and 1427. But it was clear that the attacks would keep on coming.

The time had come to go on the offensive. Starting in 1428, the Hussites began raiding their neighbors in Hungary, Saxony and Silesia. They came close to defeat when Hungarian cavalry broke through the lines of a wagon fort, but managed to drive them back with heavy losses.

These campaigns brought wealth to the Hussites, but also dissent. The iron discipline that had come from the combination of religious fervor and Jan Zizka’s leadership was fading. In its place was greed for loot.

Booty, Brutality, and Collapse

The Hussites were still able to defend themselves well. When Sigismund launched his fifth crusade in 1431, the rebels united and drove him back, the mere sound of their battle hymns putting the crusaders to flight.

But trouble was coming. Two factions among the Hussites, the Taborites and the Orphans, fell out over the spoils of their raid into Silesia in the autumn of 1431. Together they had been strong but divided they were weak. The Orphans lost 120 wagons during a fighting retreat, while the Taborites were defeated during an expedition into Austria.

Prokop was unable to stop the pillaging of his troops, and their brutalities enraged their neighbors. When a Hussite column was trapped in Bavaria in 1433, angry peasants joined the army that overwhelmed their wagon fort and massacred them.

Finally, in 1434, the Utraquist nobles gathered an army and marched against the Hussites. At the battle of Lipany, the Utraquists feigned a retreat, drawing the Hussites out of their wagon fort, and defeated them.

The rebellion was in tatters, and soon Sigismund was back on the throne.