In 1524, a revolt broke out in Germany. Peasants rose up in a war that showed the religious and social tensions that would tear Europe apart over the following centuries.

The Causes of War

The Peasants’ War was not the first revolt against the authority of nobles in Germany, but it was the most widespread the region had seen so far.

The underlying cause of the war was economic change. Following a fall in population in the 14th century, lords had given up on claiming some of their ancient rights that were no longer either useful or viable. But in the early 16th century, fresh economic changes put the squeeze on these nobles.

They tried to fix their finances and reassert their control by enforcing these ancient rights, including claiming extra taxes and limiting freedom of movement and marriage.

To peasants and townspeople who hadn’t seen these rights asserted in generations, it wasn’t a revival of legal rights. Rather it was the assertion of something new that harmed them.

They were given ideological grounds for revolt by the reformist Christians just emerging from Lutheran Protestantism. Many took the religious revolution of Protestantism as justification to revolt against oppressive authority in general. Though Luther didn’t see it that way, his influence gave the revolt a religious aspect.

Outbreak

The revolt began in the summer of 1524. At Stühlingen in the southwest, the Countess of Lupfen made fresh demands upon the peasants in her area, following a series of bad harvests that left the inhabitants already stretched thin. Hundreds of peasants responded by gathering together, electing leaders, putting together a list of grievances, and raising the banner of revolt.

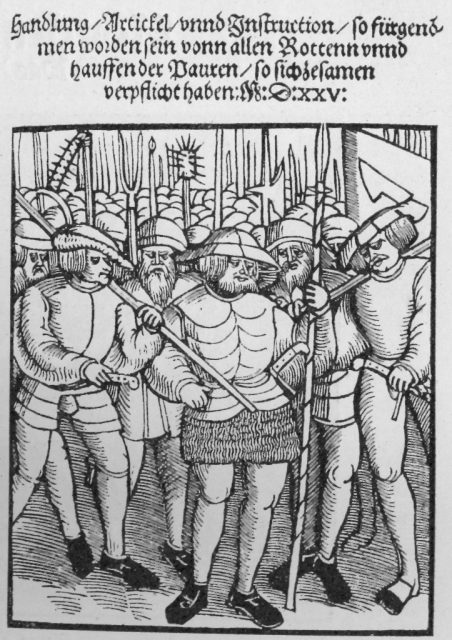

By early 1525, the revolt was spreading out of the southwest. Peasants in many parts of Germany were revolting against the impositions of their local rulers. The idea of insurrection was spread partly by word of mouth and partly through pamphlets. The printing press was still a relatively new technology, but it was one the rebels seized upon.

Thousands of copies of rebellious leaflets were printed, particularly of the Twelve Articles, a statement of principles that tried to create a common agenda for the revolt.

How They Fought

This was also in the early days of gunpowder warfare. Guns were expensive and hard to obtain, but city armories had such weapons ready for defense, so the rebels were able to get hold of them. The majority of the rebels still used more traditional weapons, such as swords, spears, and clubs.

It took time for the rebels to get organized, as most weren’t used to being part of a military organization. When they did organize, they usually elected separate military and political leaders. The military leaders were often men with military experience, such as Hans Muller and Walter Bach.

Both men had fought in the Landsknecht armies, mercenary bands which the peasants used as a model for their armies. Where a veteran could not be found, other men took command. Some of them proved unreliable in a crisis, but others became effective military commanders, such as Caspar Prassler, and Michel Gruber.

Against them were arrayed the forces of lords and princes. They used their wealth to hire mercenaries and raised feudal levies to bring in more troops. Their greater resources made it easier for them to acquire weapons and supplies as well as experienced soldiers.

The Tide of War

The first important battle of the war took place at Leipheim. There, several thousand rebels gathered in April, equipped with cannons. They were approached by the army of the Swabian League, led by Georg, Truchsess von Waldburg, a commander with experience against peasant uprisings. His superior forces scared off the rebels, giving him a victory.

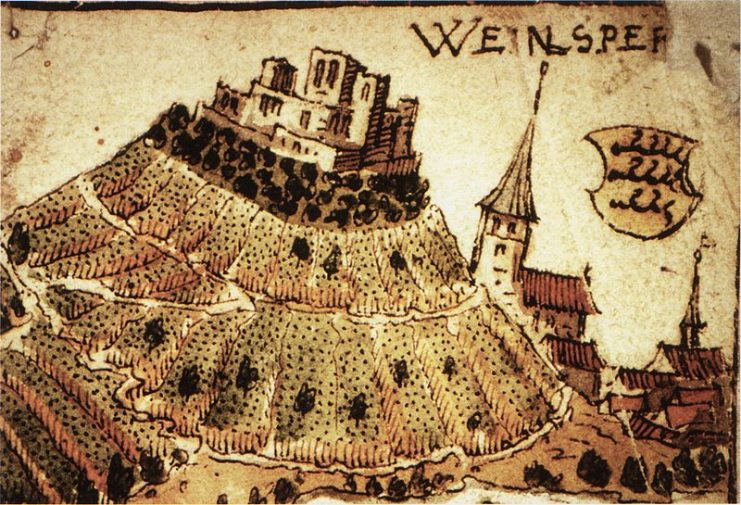

The peasants’ resentment of their oppression by nobles led to acts of destruction and brutality. Around 70 nobles were executed at Weinsberg. Wildenburg Castle was burned down.

In May, a substantial peasant army was again defeated, this time at Frankenhausen. Thousands of rebels were massacred in the aftermath.

The pattern repeated at Böblingen, Königshofen, and Würzburg. Again and again, noble-led forces with more professional armies were able to bring more force to bear, breaking rebel armies and inflicting heavy casualties upon them.

Disunity was the biggest problem holding back the rebels. Though they all shared similar agendas, they were not used to working with people from beyond their immediate locality. They could not agree upon or execute a shared strategy. As a result, the defenders of the status quo picked them off bit by bit. By the end of the summer, resistance was effectively at an end.

The End

Many of the peasant leaders were seized and executed. Among them was the painter Jorg Ratgeb, who had become a leader among the rebel armed forces. The winners showed little mercy to those from the lowest classes who had risen up against them.

For lower-ranking nobles and town authorities who had sided with the rebels, the outcome was sometimes less brutal. They negotiated peace with the princely armies, which allowed them to retain their lives and their wealth.

In some areas, the peasants won small concessions from the resurgent nobles, who were keen to prevent such a revolt from taking place again. But the overall result was a terrible failure. There was little real change, and in many places the peasants lost what rights they already had.

Read another story from us: War Wagons: One of the Strangest Military Formations Ever Seen in Europe

The Peasants’ War reflected the religious and social tensions that would lead to further wars across Europe in the centuries that followed. But at the time, its outcome was a resurgence of the exact noble power the rebels had sought to thwart.