During the Middle Ages, the fortified city of Constantinople, the imperial capital of the Byzantine Empire, was considered unconquerable. It was not the city’s large thick walls that guaranteed safety for its inhabitants, however. It was something far more terrifying than the walls and the men that defended them.

The Byzantine Empire had developed an incendiary weapon in c. 672, dubbed The Greek Fire by the Western Crusaders, that repelled enemies superior in numbers throughout the centuries. The Byzantines used a variety of names for the weapon such as sea fire, Roman fire, liquid fire, war fire and sticky fire ― all implying the characteristics of the mixture used to set ships a flame during naval battles.

Since the city of Constantinople (today’s Istanbul, Turkey) was located on the banks of a natural strait, Bosphorus, on the coast of the Marmara Sea, the invaders often used a naval force in their attempts to besiege the fortress of Constantinople. The city, in order to defend itself, as the heart of the Byzantine Empire, was in need of a superior weapon, that would disintegrate the enemy fleet, sparing the Greek fleet as much as it was possible.

The invention of the weapon is ascribed to a certain architect from Heliopolis (today’s Baalbek, Lebanon) called Calinicus. This attribution is based on the claims of a Greek chronicler, Theophanes, whose description of the weapon and its effects remains the oldest living testimony. Due to several chronological contradictions, historians had dismissed the theory that the Greek fire was a product of a one man’s design, but rather claim that it was produced in the Constantinople’s chemical laboratories by a team of experts, as a state-funded weapon project.

Therefore, the weapon’s formula was a state secret and the original ingredients of the mixture remain unknown to this day. Modern scientists continue to debate about the formula, with various proposals including combinations of pine resin, naphtha, quicklime, calcium phosphide, sulfur, or niter.

The weapon’s main trait was that it produced a fire that could burn on the surface of the water. This made it a perfect weapon for sea battles between wooden ships. The iconic image of the fire on water would cause fear among the enemies of the Empire, especially because the weapon couldn’t be reproduced by anyone else except the Byzantines.

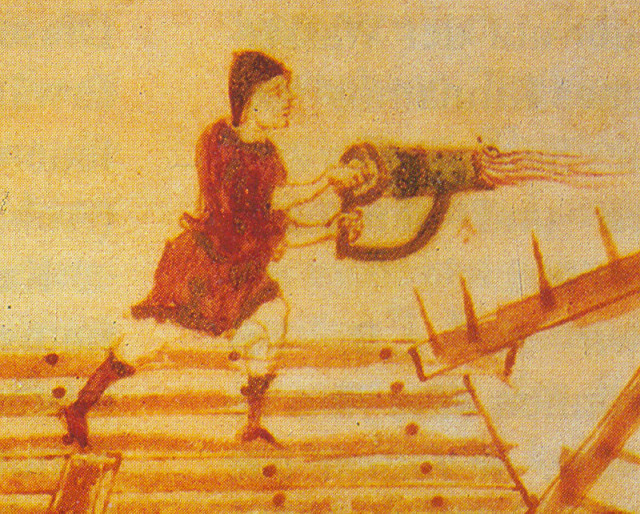

These masters of the Mediterranean Sea introduced the offensive capacities of the Greek Fire, by implementing specially designed ships that were equipped with devices resembling flamethrowers. This new weapon appeared when it was needed the most ― weakened by its long wars with Sassanid Persia, the Byzantines had been unable to effectively resist the onslaught of the Arab conquests. Within a generation, Syria, Palestine, and Egypt had fallen to the Arabs, who in c. 672 set out to conquer the imperial capital of Constantinople.

Greek fire was used to great effect against the enemy fleets, helping to repel the conquerors at the first and second Arab sieges of the city. The weapon continued to be in active use, with reports of victories gained by the advantage of the feared fire dating all the way to the 13th century. It was a vital instrument in crushing both foreign incursions by Arab and Slavic invaders and local rebellions. During the Byzantine expansion in the late 10th and early 11th century, the battle proved to be vital in a number of naval battles against the Saracens.

Even though it was never reproduced after the secret died with the Byzantine Empire, the scientists around the world agreed that the Greek Fire is best understood as a complete weapon system of many components, all of which were needed to operate together to render it effective. It also included a range of equipment and specially modified ships that contained a furnace in the decks. The main Byzantine battleship was called dromon ― large ships manned by a crew that numbered 100 to 150 sailors. One source describes the appearance of the ships equipped with Greek Fire:

“…having built a furnace right at the front of the ship, they set on it a copper vessel full of these things, having put fire underneath. And one of them, having made a bronze tube similar to that which the rustics call a squitiatoria, “squirt”, with which boys play, they spray [it] at the enemy.”

The “squitiatoria” refers to a siphon used to distribute fire on other ships. In attempting to reconstruct the Greek fire system, several characteristics were summed up by various sources. A lot of sources are untrustworthy, but a combination of claims leads to a conclusion that lists following conclusions:

- It burned on water, and, according to some interpretations, was ignited by water. In addition, as numerous writers testify, it could be extinguished only by a few substances, such as sand (which deprived it of oxygen), strong vinegar, or old urine, presumably by some sort of chemical reaction.

- It was a liquid substance, and not some sort of projectile, as verified both by descriptions and the very name “liquid fire”.

- At sea, it was usually ejected from a siphōn, although earthenware pots or grenades filled with it or similar substances were also used.

- The discharge of Greek fire was accompanied by “thunder” and “much smoke”.

Numerous documents, mainly from the 10th century, extensively praised the use of Greek Fire in both sea and land. While it was initially used as a defense weapon against invading fleets, the variants soon appeared, such as a wall mounted flamethrower against foot soldiers, large cloths soaked in the mixture that were thrown from the wall and adjusted projectiles fired by light catapults.

Some warlords of the era advocated the use of “flamethrowers” in the field of battle in order to disrupt enemy formations. Historians imply that this device must have been completely different in design than their naval counterparts, but no evidence remains to this day to confirm these claims.

Even though the Greek Fire undisputably revolutionized medieval warfare, it wasn’t perfect. Its effects could have been avoided just by staying out of its range, as it had limited range. Also, the Arabs soon concluded that vinegar was an effective combatant of the fire, so they devised methods of protection such as hides soaked in vinegar.