The Norman conquest of England was more than just the Battle of Hastings. To secure his new country, William the Conqueror had to gain control of London, fend off rebellion, and eventually blaze through northern England in an arc of destruction that made resistance impossible.

1066

The death of Edward the Confessor in 1066 left several men with claims to the English throne. Most significant were William, Duke of Normandy, and Harold Godwinson, who immediately took control of the country.

While Harold was dealing with other challengers, William gathered an army in northern France, along with a fleet to transport it. This was a huge logistical challenge. He had to win the support of his most powerful subjects for his campaign, gather the soldiers in one place, and deal with supplies and sanitation while they waited to go to war. To transport his army, an entire fleet’s worth of ships had to be requisitioned, hired, or built.

Following delays – some strategic, some due to bad weather – William crossed the English Channel, landing on the south coast of England on the 28th of September, 1066. He set up a fortified base at Hastings and sent his army to forage all across the area, ensuring supplies and forcing Harold to face him or leave his subjects vulnerable.

The Battle of Hastings

After fighting off another contender, Harold and his army made a forced march south, arriving in the area on the 13th of October. Exhausted from fighting and marching, they still came close to surprising the Normans with their arrival.

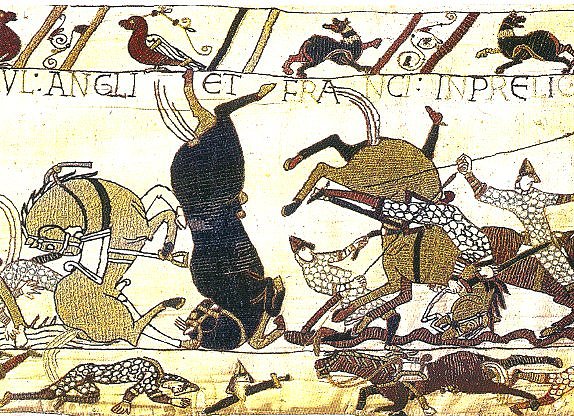

The next day the two forces faced each other in the Battle of Hastings. It was a long and grueling battle between armies that were well matched in size and skill. Harold held the high ground with a traditional Saxon shield wall. For much of the day, William struggled to penetrate this line. By combining archers and feigned retreats, he was eventually able to create gaps in the Saxon line and exploit them with his cavalry, giving him the edge.

As nightfall approached, the Saxons were clinging on, with defeat and withdrawal clearly on the cards. But then Harold was killed, hit in the face by an arrow and cut down by a group of knights. His banner fell and the army dissolved.

William had won.

Securing London

For hundreds of years, London had been the key to controlling England. Though not geographically central, it was the largest and most powerful city, the heart of the economy. As a group, its citizens could be as important a political player as any magnate or prince.

Two archbishops, Edwin and Morcar, set up base in London and resisted the Normans. Their plan was to make the young Edgar Aetheling king, retaining Saxon control of England.

William approached London indirectly, taking a long, snaking around the southeast. He secured the important port of Dover and the vital religious seat of Canterbury.

A sortie from London attacked the Normans but was defeated. The Normans, in return, tried to enter the city from the south but were unable to cross the well-defended bridge.

Pillaging as they went, the Normans took a broad loop to the west around the city. This had three effects – scaring the Londoners about the consequences of resistance, cutting them off from support, and allowing the Normans to attack from the north, avoiding the problem of approaching across the Thames.

London surrendered, and William was crowned king there on Christmas Day.

Uncoordinated Revolt

Though the southeast was conquered, other parts of England remained resistant. Everywhere from the Ely marshes in the east to the Welsh marches in the west, from Durham in the north to Cornwall in the south, rebels held out. Unable to match the Normans on the field of battle, they often took to guerrilla tactics, raiding from bases in the hills, forests, and swamps.

These rebellions were uncoordinated. Edgar Aetheling was too young and lacking in influence to unite them. Foreign interventions from Scandinavia were as unpopular as the Normans themselves. As a result, there was no figurehead to combine behind. Rebellious Exeter resisted a siege by William for only 18 days before surrendering. Local troops drove off forces led by Harold’s illegitimate sons in the southwest. A swift march north ended early resistance there, and castle building secured Norman control of the Midlands.

The Harrying of the North

The greatest acts of resistance took place in the north. The Norman Earl Robert was killed in Durham in January 1069, beginning a fresh wave of revolt. The rebels besieged the castle at York, the key city of the region.

William acted decisively, swiftly marching north with an army at his back. Surprising Edgar Aetheling’s forces at York, he routed them in street fighting. With the north apparently brought to heel, he headed back south.

In the fall, a Danish army landed in northern England and joined up with Edgar’s rebels. They quickly captured York, and their success triggered further risings in the south and west.

Recognizing that Edgar and the Danes were the biggest threat, William left trusted lieutenants to deal with the other revolts and marched north. His opponents were too afraid of his skill and power to face him in battle, so withdrew. Dividing his forces, he was able to contain the Danes while hunting down and crushing the rebels at Stafford. Prevented from taking York, the Danes agreed to leave the country.

What followed is the most infamous part of the Norman invasion – the Harrying of the North. From January to March 1070, William devastated a band of territory across the width of the country, creating a dead zone from which rebellion could not be raised. Fear was reinforced by castles built to visually and militarily dominate the areas around them.

It had taken four years and many campaigns, but William had finally conquered England.

Source:

Nicholas Hooper and Matthew Bennett (1996), The Cambridge Illustrated Atlas of Warfare: The Middle Ages 768-1487.