Far from home and at constant threat of attack, the armies of the Hundred Years War between England and France were reliant on supply lines to keep them alive. They needed to be fed and watered, their horses supplied with fodder, their feet shoed for long marches. They needed weapons and armour before they set out on campaign, replacements as these were lost or damaged, new arrows as old ones were used up.

Without the backing of a modern bureaucracy and transport network, how was the difficult task of supplying these armies achieved?

Why Not Live Off the Land?

The Hundred Years War was hugely destructive for the lands it was waged through. The English, in particular, made use of chevauchees, long pillaging marches, to punish the French for adherence to their king. So why not rely on these tactics all the time? Why not live off the land?

The answer for the French was obvious. The war was taking place on their home ground, and they did not want to harm their loyal subjects – people who they were trying to prove they could protect.

But the English also had reasons not to rely on pillaging most of the time. Letting soldiers of the leash to pillage led to a breakdown in discipline. Punitive raids would only bring lands under them if the inhabitants believed that surrender would make them safe from pillaging. And some armies, such as the force occupying Calais, could not go raiding as they were defending a base, one that was often surrounded.

Prise and Purveyance

The two kingdoms used similar systems to obtain food for their armies – the French prise and the English purveyance.

Under both systems, government officials went out to the localities to demand food for free or at discounted rates. This was backed up by laws which obliged farmers to provide certain supplies when the crown demanded.

Early in the war, this caused problems for the English King Edward I. Trying to push his rights of purveyance to their fullest extent, he faced resistance from people who were already paying taxes to fund his armies. Corrupt practices by purveyors – the officials collecting the supplies – did not help. As time passed, Edward eased off in his demands, and relations with his people improved.

Presenting Arms

Soldiers were expected to turn up ready for war. In England, this meant that each locality or landowner responsible for providing a set number of troops was also responsible for equipping them with specific armour and weapons. In a similar way to purveyance, owners of geese had to provide six feathers from each one at a low price, to help in making arrows.

But these feudal obligations were insufficient to provide replacement equipment as the war raged on. In both kingdoms, the royal governments developed institutions to maintain supplies such as arrows, shields, and lances. In 1360, the Keeper of the King’s Arms had 566,400 arrows at the Tower of London. Twenty years later, only 24,000 remained.

The Beginnings of Uniforms

Variations in what equipment men turned up with could cause problems. If they didn’t have the right weapons and armour then they could become a weak link in the army, unable to properly fulfil their battlefield role. To counter this, uniform equipment began to emerge during the war.

The most uniform troops were those deliberately recruited and equipped as one body of matching men. For example, in 1340 the town of Tournai mustered 2,000 identically clothed soldiers to fight for the King of France.

The other mechanism for achieving uniformity was the local muster. This was the moment when both the absence of men and deficiencies in their equipment could be noted. Local authorities could then search out equipment to fill the gaps in what men had, sending them to war not in a uniform as we think of it but at least with every man equipped to legal standards.

Horses

Horses were among the most important and most vulnerable pieces of military equipment. They reduced the strain of marching around the country and allowed knights to launch devastating mounted charges but often died due to the hazards of these tasks. They were also among the most expensive pieces of equipment to supply.

Knights generally provided their own horses, and might take several with them in case one was killed or injured. They could claim compensation from the crown for any horses lost in battle, something that was often written into contracts in both countries. And so horses were evaluated before they were taken to war, given a recorded market price so that compensation claims could be made.

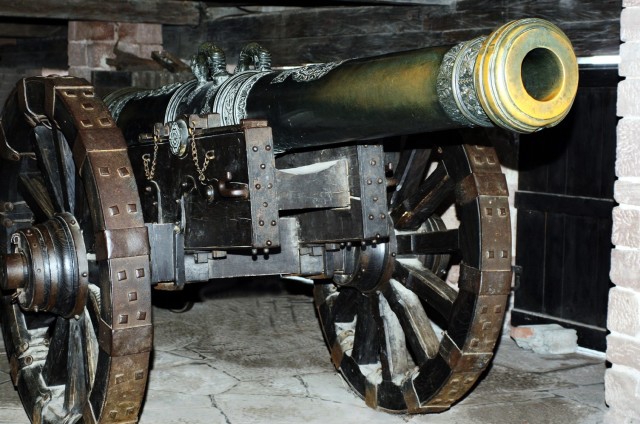

Artillery

The Hundred Years War saw some of the first uses of cannons both in sieges and on the battlefield. In France, these costly devices were provided almost entirely by the crown, and in both countries royal officials took responsibility for overseeing the provision of artillery. Specialists such as Jean and Milet de Lyon in France and the Byker family in England were responsible for ensuring these supplies.

In this way, artillery played a part in the gradual centralisation of military supply under royal governments.

Transport

Bringing all of these supplies together was a monumental task. What men brought for themselves at least carried with them, but when food, weapons, and other supplies were being gathered later in a campaign, arrangements had to be made for transport.

This began with gathering supplies in one place. For weapons, this was the Louvre or Bastille in France and the Tower of London in England. French supplies could then be loaded onto wagons or river boats and sent out. English supplies had to be transported to a channel port, loaded onto ships and protected from French-commissioned pirates as they crossed the Channel. Only then could they be sent to the men needing them.

Source:

- Christopher Allmand (1989), The Hundred Years War: England and France at War c.1300 – c.1450.