Few generals throughout history can say that they were undefeated over their career, fewer still can be credited with doing so with a mob of peasants and militia forces fighting against professionally organized crusades while being partially and later completely blind. Jan Žižka, born in 1360 had a great deal of experience as a mercenary, and was from a small town in Bohemia, but also was a Chamberlin to the Queen.

At the massive battle of Grunwald/Tannenberg, Žižka fought as a Czech mercenary on the victorious Polish/Lithuanian side, though before the battle he supposedly offered his services to the Teutonic order, and still before that he may have made a living as a sort of bandit. It is during this battle where he seems to have sustained the injury that claimed one of his eyes, but he still fought on.

He was not a commander, but he does seem to have learned a lot from participating in one of the largest field battles of the medieval period. By the 1410 battle of Grunwald, Žižka was already 50 years old, but his legendary story was just beginning.

Well before the reformation’s Martin Luther, a Czech priest by the name of Jan Hus, had a lot to say against the Catholic church. He mainly protested against the system of paying for absolution of sins, and against the immorality of the church in general. Jan Hus was eventually burned at the stake for heresy, prompting a Czech/Bohemian uprising of his followers who would be known as the Hussites. The revolution was upgraded to much more complex war when the Hussites invaded the Prague town hall and carried out the first defenestration of Prague by throwing over a dozen members of the town council out of the upper floor windows. The Bohemian King Wenceslas died soon after, leaving a power vacuum and leading to all-out war between Hussites, Bohemian Royalists and others, including sanctioned Crusades against the Hussites.

Jan Žižka commanded an initially very small force of farmers and poorly trained militia and sought to train them using what they already knew. This meant that most of the farmers were trained to use their flails, usually a tool for threshing wheat, as weapons of war. Žižka also was adamant about the inclusion of gunpowder when possible and pioneered the use of early pistols and field cannons.

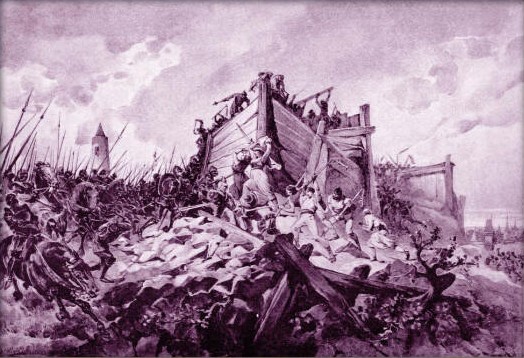

While out in the field with about 300 infantry Žižka’s forces were ambushed by 2,000 Bohemian Royalists, most of which were cavalry. It was here where Žižka utilized his inventive wagon fortresses. These were heavily fortified wagons using thick wooden planks, often reinforced with iron. The wagons held 16-22 men, each with specific roles. Some were crossbowmen and hand gunners, some wielded pikes for warding off closer combat, and there were dedicated shield carriers and drivers if needed. Some wagons also focused on carrying cannons to punch through enemy lines.

Using these wagons, Žižka was able to turn the tables on the ambushers and escape while dealing heavy casualties to the many times larger force. Later a pitched battle was fought with the same number of troops and this time, Žižka was able to prepare the battlefield better. He placed wagons with ponds and marshes protecting the flanks. After several failed charges against the wagons, the lighter and more rested Hussites were able to venture out and attack the slowed Royalist cavalry. These victories gave Žižka more credibility and soon he was tasked with the defense of Prague against the newly appointed king of Bohemia, Sigismund.

Sigismund had control of two castles in Prague and had a large army, complete with groups of Crusaders, up to 100,000 strong ready to besiege the main city held by the Hussites. Žižka decided to heavily fortify the hill of Vitkov just outside of Prague. This prevented a full encirclement of the city, causing the siege to be ineffective. When Sigismund sent forces to take the hill they were repulsed and a flanking counterattack sent the Crusaders fleeing. The defenders on the hill may have been as few as 60 men as well, holding firm with well-built fortifications and effective concentrations of firepower. Soon after this Sigismund abandoned the siege and the Hussites secured the castles in Prague.

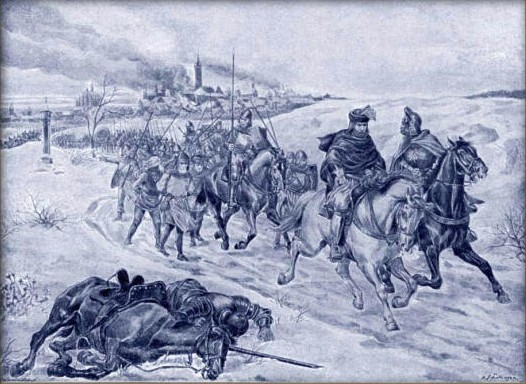

After the defense of Prague, the Hussites secured most of Bohemia and elected their own leaders, with Žižka being one of the many chosen. A war of constant conflict ensued where Žižka traveled all over, using his war wagons to great effect. When traveling the wagons were used as transports and could even hold mobile forges for the upkeep of the weapons, especially the still primitive gunpowder weapons. Žižka’s legend continued to grow as he consistently won battles despite terrible odds. He was casually known as “one-eyed Žižka” by his men.

During a siege Žižka was wounded by an arrow and lost his other eye, becoming completely blind, but still commanded his troops. The extent of the blindness is unclear, as both eyes were blinded by war wounds. It is possible that he still maintained some semblance of basic vision, discerning light and simple shapes, but entirely plausible that he was absolutely blind.

At the battle of Kutná Hora, Žižka again faced a force under king Sigismund much larger and more professionally trained than his own. When a section of Hussites was surrounded Žižka prevented their annihilation by bombarding the Royalist cavalry with field artillery, one of the first recorded uses of offensive artillery in the field. With the bombardment keeping the encircled troops safe for the moment Žižka organized his war wagons into a column and charged them through the encirclement with incredible success, saving the trapped troops and turning the tide of battle, all while functionally blind. Sigismund was barely able to get away with his life.

Following this, Žižka harassed the larger force, constantly raiding and ambushing them. Whenever they counterattacked he baited them into attacking the fortified wagons before launching his own counterattack. Žižka did not often fight with the wagons despite them being his key invention. Instead, he fought from horseback and was well known for wielding a heavy mace with devastating effect. This powerful image simply solidified his position as a leader of the Hussites as a man who could lead armies of outnumbered farmers and had no problems fighting in the front lines.

Žižka would eventually have to fight against fellow Hussites as the group split into feuding factions with the repulsion of the Royalists and crusades. In every instance Žižka was incredibly effective, using a mix of high ground fortifications and expertly timed counterattacks to win the day. His victories helped to periodically unify the Hussites against external threats.

Still campaigning, blind and in his sixties, Žižka eventually fell fatally ill with the plague and died in 1424. Though unproven it was said that Žižka’s dying wish was for his skin to be made into war drums so that he could still lead his men to battle. his loss was so profound that his followers declared their faction name as the Orphans because they had lost their collective father.

After some years, the acclaimed general Prokop the Great would succeed Žižka. Žižka would die an undefeated general. His enemies feared both his tactics and his martial skill, in surviving statues he is often depicted wielding his distinctive mace.

An unknown source spread this quote after his death: “The one whom no mortal hand could destroy was extinguished by the finger of God”.

By William McLaughlin for War History Online