Fought from 1337 to 1453, the Hundred Years War was one of the most significant conflicts of the late Middle Ages. As the Plantagenet kings of England and the Valois rulers of France vied for power, thousands of men were thrown into the fray.

Though England and France were separated by the English Channel, the Plantagenet kings controlled large swathes of France, and so much of the fighting took place on land. A variety of troop types went to make up their armies.

Infantry

The majority of troops were infantry. Recruited through feudal obligations to Lords, hired for money, or brought in as part of mercenary companies, these men were the massed ranks filling battlefields and the soldiers garrisoning towns and castles.

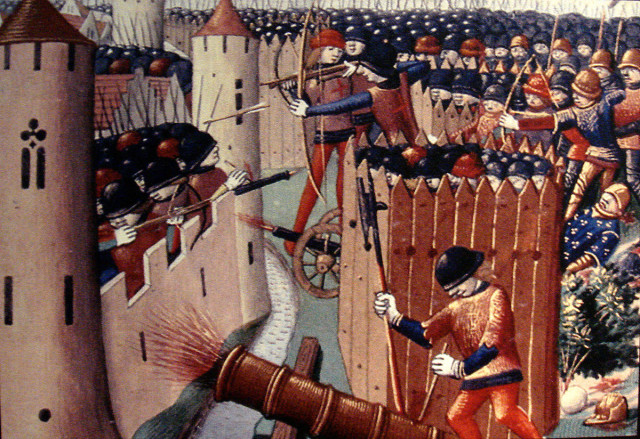

Infantry were particularly important because of the role of sieges in the Hundred Years War. It was a war for control of territory, and that control could only be achieved through holding fortified positions in castles and towns. Infantry manned the walls in defense and stormed the ramparts in the attack.

Though there were standards for the equipment men were meant to bring when mustered, the results were mismatched and haphazard. Infantrymen were not wealthy. They wore whatever scraps of armor they could get, the most common and important being metal helmets. Most carried a sword, a mace or an axe for close quarters fighting. Those forming battle lines usually had spears or polearms with which to gain reach on their opponents and fend off cavalry.

Missile Troops

A significant proportion of the infantry were armed with missile weapons. This was particularly true in the English army, where they commonly made up between three-quarters and nine-tenths of the army in the 15th century.

English and Welsh longbowmen played a decisive part in many battles. Like the rest of the infantry, they were equipped with whatever armor they could afford, from leather brigandines to chainmail. They carried swords and daggers for close quarters fighting, in which they also sometimes used the mallets they carried for hammering stakes into the ground. Some could fire ten arrows in a minute.

French missile troops were usually crossbowmen and often mercenaries, such as the Genoese, who served at Crécy. These men carried large shields called pavises, behind which they could shelter to reload.

Men-at-Arms

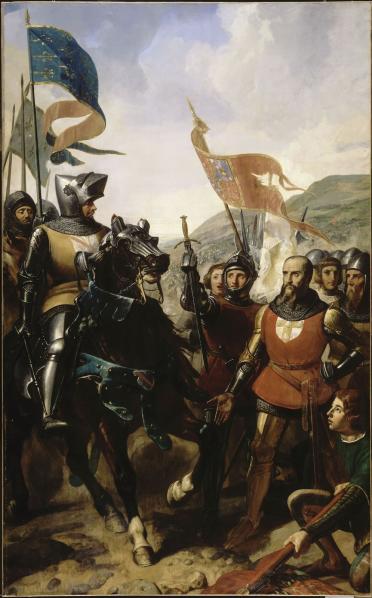

The elite strike force of both armies was made up of men-at-arms. Commonly referred to as knights, they were actually a mixture of knights, nobles, and men of lower social station who had enough wealth to obtain heavy armor. Trained from youth as warriors, they commonly fought from horseback, but could also fight on foot, as the English men-at-arms did at Crécy, Poitiers, and Agincourt.

Always heavily armored, they started the war in chainmail and by the end often wore plate armor, thanks to improvements in armoring technology.

Men-at-arms used lances in the charge, carried swords for close quarters work, and sometimes carried maces or pole-axes when fighting on foot. At the start of the war, they always carried shields, though this became less important as armor improved.

The French were able to field far larger groups of men-at-arms but tended to use them as a blunt instrument of attack, leading to battlefield disasters such as Agincourt.

Hobelars

The other form of cavalry deployed in the Hundred Years War was the hobelar. More lightly armored than men-at-arms, their horses did not need to be as powerful, making them cheaper to equip.

Hobelars were less likely to fight from horseback, as they were less equipped for a heavy charge than men-at-arms. Their steeds were as often a way of getting around, set aside once the battle began.

Hobelars came into their own away from the large battlefields on which men-at-arms found fame. Instead of fighting the enemy face-to-face, they used their mobility to harass them along borders and skirmish for armies. They protected the English troops in this way during the siege of Calais in 1346-7, while French hobelars harassed English borders during the 1370s.

Artillery

At the start of the war, artillery was used only for sieges. But a new weapon was joining the siege train, and it would soon play a part on the battlefield. This was the cannon.

The first notable use of cannons in the Hundred Years War came at the Battle of Crécy in 1346, when Edward III deployed his artillery to intimidating effect. Unlike mechanical artillery, cannons could usefully serve on the medieval battlefield. In the early days, when they were unfamiliar to many soldiers, they could be as intimidating as they were lethal. They improved greatly over the course of the war, and the Earl of Shrewsbury was killed by one in the final Battle of Castillon in 1453.

Cannons also changed siege warfare, smashing the older tall, thin walls, cracking opens towns and fortresses, and forcing the French to build more sophisticated defenses.

Leadership

The armies were often led by their kings. Under them were the great nobles and beneath them the lesser nobility. The social hierarchy of peace time also applied in war.

A few men of minor nobility, such as Bertrand du Guesclin, rose to prominence through service in the war. At times, professionalism and experience became more important in gaining command than noble upbringing. At other times, social standing trumped skill. A noble education that emphasized leadership and warfare ensured that all commanders had at least some knowledge of what they were doing.

The Size of Armies

The armies varied in size, from bands of a few dozen men fighting border skirmishes to the 25,000 French warriors at Agincourt. These armies were small by modern standards but mobilized a significant portion of the upper ranks of society, as well as humble men and mercenaries. Equipping and supplying even forces of this size was a huge feat.