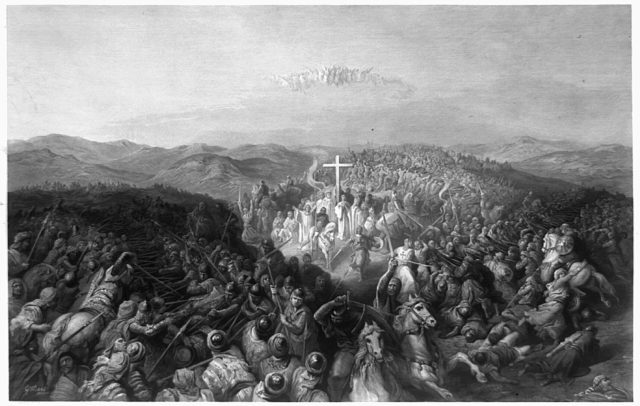

A knight stands on the walls of Jerusalem, staring out at the parched land beyond the city. He is weary from weeks of travel and fighting, his clothes blood-stained, his body sweating in the unfamiliar heat. He has come here on a crusade, to fight for Christendom, his immortal soul and the material benefits war can bring. He is a stranger in a strange land.

What does a man like this think about his situation? How is he feeling? What has brought him to this point?

Understanding the Crusader Mind

Any attempt to understand the feelings and thoughts of long dead people involves some speculation. We infer things about their state of mind from the words and physical remains that they leave behind. These are always incomplete and are harder to find for poorer people, including thousands of the lowly but devoted volunteers who joined the First Crusade.

Yet, enough accounts remain for us to draw conclusions about what was happening in the minds of medieval crusaders.

Hope

One of the few things we can say for sure about the poorer crusaders was that they hoped to find a better life in the Holy Land. A chronicler at the time described entire families joining the First Crusade, taking all their worldly goods with them. They left economic hardship, social disorder and a dangerous outbreak of the poorly understood ailment ergotism. Jerusalem and its surrounding area held out the hope – however desperate – of a better life.

Excited

Wealthier crusaders, for whom we have better evidence, approached these campaigns from a different perspective. They were not beset by a struggle to survive in the same way as peasants. For them, the crusades were an exciting opportunity.

We see this excitement in the preparations for a crusade. When King Louis VII of France took his crusading vows in 1146, St Bernard of Clairvaux encouraged such passion in the crowd that they ran out of the cloth crosses made to mark out new crusaders, and Bernard tore his own habit into strips to make more. On other occasions, men became so excited at the prospect that they branded crosses onto their bodies.

Devout

While social and material concerns helped motivate crusaders, the religious element should not be underestimated. Crusading vows were given in large public ceremonies overseen by priests. Men wore crosses throughout the crusades. The special place Jerusalem held in Christian hearts added to the sense of undertaking a religious pilgrimage.

Some men even gave up material wealth to undertake this holy service. Fulk Doon donated a large amount of property to the church in 1096 before setting out on crusade, a crusade he joined as religious penance. Even the language of the chroniclers reflects this devotion, with frequent biblical allusions.

Saved

For the first time, crusading turned warfare into a devotional act which could be used to save men’s souls. For men of violence, who risked damnation with many of their warlike activities, the opportunity was incredible. They could make certain of their eternal salvation while continuing the lives they enjoyed, rather than having to retreat to a monastery or undertake a long peaceful pilgrimage to put themselves right with God.

A sense of relief and safety doubtless filled many minds at this thought.

Nervous

Not everything about crusading was positive. Men felt trepidation both for themselves and for those they left behind. This was shown in acts such as Stephen of Blois’s gift of a wood to the Abbey of Marmoutier before he left on crusade, a gift given in return for their prayers for both him and his family while he was away.

It is easy to see why crusaders were nervous for themselves. Going crusading was a dangerous and costly business. Whether they succeeded or failed, they risked injury, death, and financial ruin.

For the families and property they left behind, there was the risk that opponents would take advantage of a noble’s absence to launch attacks, whether political, financial or physical. Within six weeks of William Trussel’s departure on crusade in 1190, his wife was murdered. The same happened to Peter Duffield’s wife when he left on the Fifth Crusade.

There was also a risk of increased lawlessness, as the absence of so many senior nobles on crusade left a gap in the group that maintained law and order.

Proud

Serving on a crusade could hugely increase someone’s social status and public profile. When the crusader Bohemond of Taranto toured France in 1106, he was undertaking a triumph like those of the Roman emperors. He lectured on his experiences to large audiences. Nobles flocked to him seeking the opportunity to be godparents to his children.

Generations on from the First Crusade, families still showed pride in the part their ancestors had played in that war.

Criticised

When the crusaders succeeded they were showered with praise, but when they failed they became subjects of huge public scorn.

The crusades were God’s war, the crusaders his weapons. Being infallible, God could not be blamed for failures during the campaigns, nor could these failures be attributed to superior qualities in non-Christian opponents. That left only one group to blame – the crusaders themselves. If a crusade failed or a battle was lost, then they had proven themselves unworthy instruments of the divine will, failing God and their fellow Christians. As things fell apart from 1101 AD onwards, they were roundly criticised for this.

Reaping the Benefits

Crusaders gained many religious and legal privileges, which by the 13th century had become clearly defined. They included exemption from taxes and feudal duties, the pause or swift resolution of legal cases, a pause in the repayment of debts, access to a personal confessor capable of absolving many sins, and even release from excommunication.

These benefits would please any crusader and played a heavy part in the decision of the more coldly calculating to join a crusade.