We’ve all seen medieval executioners in movies and cartoons: the oversized man carrying a large axe, masked with a hood, who brought death to the condemned. Little else is provided in these productions about their lives beyond the executions, but what was it like to be an executioner in the medieval period? It wasn’t all sunshine and rainbows, that’s for sure.

The job definitely had its pitfalls, but it also had its perks… It was a tough job, but someone had to do it.

Becoming a medieval executioner wasn’t voluntary

People weren’t lining up to become executioners during the medieval period. In fact, it was a task that was typically forced upon those who ended up in the profession. Capital punishment was a necessity of the era to maintain law and order, but the reality is very few were willing to take on the job.

While salaried executioners have existed in the past, the job was usually thrust upon either the oldest male relative of a criminal sentenced to death or a former criminal. They were issued warrants that authorized them to carry out the executions, which also laid out that they were exempt from charges of murder and absolved of sin in the eyes of church, as they were simply doing their duty.

However, this didn’t prevent the masses in the medieval period from believing executioners were destined to be damned in the afterlife. Many also believed it took a certain type of person to carry out such a task, which explains exactly why criminals were told to perform such a gruesome job.

Did medieval executioners really dress in all black?

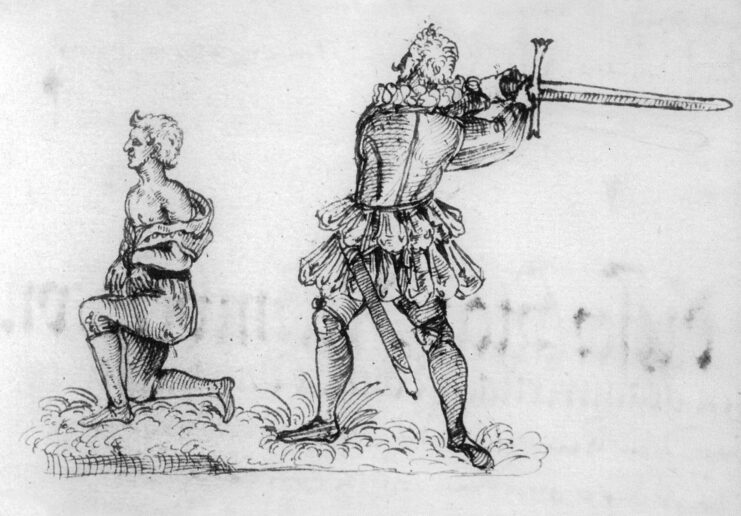

Media representations of medieval executioners often have them dressed in black hooded robes, with a mask to conceal their identities. However, this couldn’t be further from reality for the average executioner of the time.

In Scandinavia, those chosen to do the job were maimed, having either one or both of their ears cut off. That way, everyone in the community knew exactly who they were. In other countries, executioners were branded on their heads with hot irons, so that they couldn’t be separated from their profession – their job was actually written on their faces.

Being ostracized by their own communities

As everyone in the medieval era was aware of who the executioners were in their community, it was easy to ostracize them. Killing people for a living was a societal duty, but that didn’t mean others were accepting of it.

They were actively barred from engaging in day-to-day life and, where possible, executioners and their families were forced to live on the outskirts of towns, far from others. If this wasn’t possible, they were confined to residences near public lavatories, brothels and leper colonies. The general public considered executioners to be unclean and treated them as such.

Medieval executioners were also denied citizenship where they served and were barred from several establishments, including churches and bathhouses. Practically all public locations were off the table. Some places even enacted laws that outlined what executioners were and weren’t allowed to do.

Being a medieval executioner impacted the entire family

This poor treatment had a resounding effect on the families of executioners, as their proximity to the profession led them to be shunned by their communities. The only people who socialized with executioners and their relatives were questionable figures, such as criminals, as well as others in the occupation. Strong connections were made that fostered a whole subculture of life as a medieval executioner.

Unfortunately, anyone forced into the job wound up prescribing their children to the same fate. This led to several generations of executioners within a singular family, creating strong dynasties throughout the medieval period and beyond, such as the Sanson family, the Deibler family and the Pierrepoint family.

Medieval executioners could be killed in more ways than one

Several medieval executioners performed their duty with a great deal of professionalism, seriousness and efficiency, which, in hindsight, could be considered highly respectable. However, they approached their profession in such a way for more reasons than just reducing the suffering of their victims.

Doling out death was definitely not a cushy gig and executioners were at risk of it themselves each time they performed one. If they somehow botched the execution, caused undue suffering to their victims, or simply performed their job with incompetence or unprofessionalism, they could find themselves subjected to the wrath of the community.

Executioners also had to worry about the vengeful relatives of victims, as, despite them only doing their jobs, they were still the ones bringing death upon these individuals’ loved ones.

Additionally, there was the added pressure of laws, which stated that, should executioners not be able to perform their task within certain parameters, they could be sentenced to death themselves. For example, if it took them more than three swings of a sword to behead the victim, they could suffer the same fate.

Hidden benefits to taking the job

Not everything about being a medieval executioner was bad. If you strip away all that was just discussed, the job actually had its perks. First of all, executioners often received bribes from criminals or the family members of the condemned. This was in hopes of making death as speedy and painless as possible or providing extra comfort in the days leading up to the execution. They were also granted any possessions that were on the victim at the time of their death.

Additionally, executioners were tasked with other jobs that could fetch them a pretty penny. They were often in charge of clearing all animal carcasses from specific regions, which meant they had sole access to valuable hides and teeth. They were also in charge of driving lepers out of town. Considering how no one else wanted to take on these tasks, executioners could charge a handsome amount for their services.

In some places, due to their expulsion from society and inability to shop freely at markets, executioners were granted permission to tax merchants on the various items they sold. Executioners still needed food and drink to survive, and their occupation allowed them to demand free goods.

What did being a medieval executioner pay?

When it came to pay, medieval executioners had it pretty good. While it’s difficult to value the cost per beheading, hanging and flogging in today’s numbers, comparing their price to those of other occupations at the time has helped present a clearer picture.

In the 13th century, an executioner could make five schillings per execution. Comparatively, that’s about 25 days’ worth of work for other skilled tradesmen of the period. By the 15th century, they could earn 10 schillings per killing, about 16 times more than tradesmen made in a single day.

Executions weren’t as common as you might think

One thing many get wrong about the medieval period is the amount of executions that took place. While, yes, capital punishment was one of the foundations of justice at the time, there really weren’t that many happening overall. After decades of work, some executioners only recorded a few hundred executions, meaning they had to take other jobs to make ends meet.

Beyond the aforementioned tasks, they’d dispose of corpses, collect taxes from the more unsavory members of society and empty cesspools. Surprisingly, executioners also worked as medical practitioners. Serving as doctors or surgeons, they helped care for the community that shunned them. This was due to their knowledge and experience in torture, which granted them an intimate understanding of human anatomy. They were often called on to help treat ailments and perform surgeries, if necessary.

Case of Frantz Schmidt

A unique executioner by the name of Frantz Schmidt paints a slightly different story than the average one during the medieval period.

Operating in 16th- and 17th-century Germany, Schmidt was destined to take up the profession because his father had been forced into it. He was provided a robust apprenticeship to learn the ins and outs of the job. He served as his community’s executioner for almost five decades, performing 394 executions, and also tortured a similar amount of people.

Interestingly, Schmidt found work elsewhere as a doctor, having recorded serving over 15,000 people in this role, earning him the respect of his community. This granted him a pretty lenient life, as he was allowed to participate in far more activities than other executioners had in the past.

His professional approach to the job earned him an audience with Nuremberg authorities and Ferdinand II, Holy Roman Emperor, using the opportunity to convince them to restore his family’s honor.

More from us: The Evolution of Guédelon Castle – A 13th-Century Castle In the Modern Era

Thanks to not only his own account, but also a letter provided by city council members applauding his character and duty, he was granted citizenship at 70 years old. Ironically, it was his dedication to his career as an executioner that cleared his family name of the stigma it carried.