Mehmet II, known as Mehmet the Conqueror, was one of the greatest military commanders of his day. The Ottoman Empire under his rule was vast, stretching in every direction, north, south, east and west. In the middle of the fifteenth century the sultan had set his sights on the coast of the Black Sea, which was at the time under the control of the Voivodes of Wallachia, a broad realm which marked a line between the advancing border of the Ottoman Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary.

Wallachia had long been pushed and pulled between these two opposing powers, with one or the other attempting to control the throne, extort tributes or set puppet governments in place.

In 1456, the control of the throne of Wallachia had been taken by one who would not be a puppet to either power. His desire was for his country to maintain its independence, but his hatred for the Ottoman Turks was boundless and terrifying. The king of Hungary respected him, and that respect was grudgingly returned.

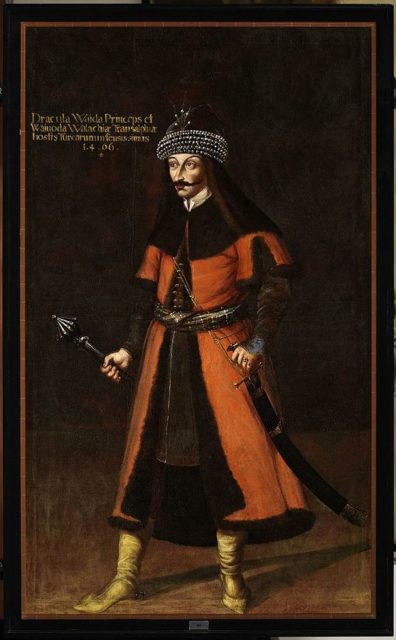

Distant blood ties, a similarity of religion and a shared enemy were good reasons for mutual respect. He was Vlad III, whom they called Dracul, after the Order of the Dragon of which his father had been a member. Vlad Dracul was a ruthless, cruel and feared individual, merciless in his methods, driven and extremely intelligent, but prone to fierce fits of rage during which none could reason with him.

His hatred of the Ottomans was well known, as was the story behind it, but the deeper reasons always remained dark. Close to nobody, Vlad did not speak of his childhood or of the trauma which had twisted him into what he had become.

Nobody knew quite what had happened, but all knew that he had spent his formative years as a hostage at the court of the Ottoman Sultan, with his brother Radu. While Radu had thrived at the Ottoman court, eventually converting to Islam and being given command of troops in the Sultan’s army, Vlad had developed a hatred of the Ottomans, which bordered on madness.

When Vlad had regained the throne of Wallachia the Ottoman Sultan sent envoys to him ordering him to pay a tribute to the Empire. Vlad not only refused, but killed the envoys, ordering that long nails should be driven through their skulls into their brains. Mehmet, who was engaged in a siege at the city of Corinth, sent his General Hamza Bey to deal with Vlad.

The Wallachian ruler ambushed Hamza, capturing him and most of his army. Mehmet, abandoned his siege, marched in haste toward the Danube, the great river which marked the Western border between Wallachia and the Ottoman Empire. Vlad marched to meet him.

When Mehmet arrived in the lands West of the Danube he found them devastated. Villages and towns had been burned, fields had been torched, wells had been poisoned. Everywhere they went they found the horrible evidence of Vlad’s presence. Around the burnt husks of villages and along the lengths of empty road there were set high wooden stakes, sharp and thick, and on each one was the body of a person.

Men, women, children. The Sultan’s troops marched toward the Danube sick with horror, and a cold rage built in them. The corpses were bad enough, but here and there a stronger person had been set up on a spike in such a way as to not be killed outright. These poor individuals croaked and gurgled at the passing soldiers, and Mehmet ordered that they should be killed with arrows as a mercy. He was cold with fury.

Vlad’s army contested the river, but they were outnumbered, and after a fierce exchange Vlad retreated and the Sultan was able to cross in force. They were headed for the Wallachian capital by the fastest road, but it was a march of some days.

As they advanced they found that Vlad had turned his viciousness against his own people and his own land, so as to deprive the Sultan’s forces of any supplies on the way. Again, villages had been burnt, wells poisoned, and innocent people killed in the most horrible ways. Mehmet was advancing into a desert of death.

On the 17th of June 1452, still some days out from the Wallachian capital, Sultan Mehmet made camp. The camp was a splendid sight, huge and colourful, rows of white tents stretching into the distance, banners flying proudly. There was music, the smell of roasting meat, and a haze of smoke from countless little charcoal braziers.

His army was huge, and at the heart of it was his great tent and pavilion, intricately woven with decorations of gold and red. They camped in the morning, and he would rest his force for a day and a night, before pressing on.

During the early afternoon, a stocky little man with a high turban and a heavy black mustache slipped into the camp. He was dressed like a member of the Turkish landed knights, the Sipahi, and he spoke in a fluent, unaccented Turkish so that none questioned his presence.

He moved through the camp, exploring and taking careful note of everything, the stabling for the horses and camels, the wagons of supplies, the tents for the Janissaries, the mercenaries and the Sipahis.

By the end of the afternoon, he stood in front of the tent of the Sultan himself, and he stared at it for a long time. Then he turned and carefully traced his way back to the main gate, before slipping back out of the camp. He had a horse tethered nearby, and when he found it he rode like the wind to rejoin his own army.

The King of Wallachia and commander of her armies, had used his knowledge of Ottoman language and culture to spy out his enemy’s camp for himself, and probably better than any agent could have done. The risk of it appealed to him, and now he would use his knowledge to launch an attack directly on the hated Sultan. He would attack that very night.

Just before midnight, he himself rode boldly up to the gate of the Ottoman camp. In perfect Turkish he ordered the guard to open the gate. The order was obeyed, and in the dark, he and a picked body of horsemen flowed in. Their secrecy held for long enough that most of Vlad’s soldiers were inside before any alarm was raised. Then chaos was loosed, and with flaming torches held high the Wallachian forces tore through the Ottoman camp. They pushed against the horses and camels, killing many. They set fire to tents and wagons. Vlad and his own personal bodyguard drove against the Sultan’s tent, but they found it empty. They set fire to its opulent fabric and rode back toward the gates in wrath.

By this time the Ottoman commanders had managed to achieve some order in the chaotic camp. Resistance was beginning to strengthen. Vlad sounded the retreat, and his horsemen rode away. In the night their torches streamed behind them as they thundered away, leaving death and destruction in their wake.

The night attack had failed to kill the Sultan, but many thousands of his men had been killed in the confusion, as had many of his horses and camels.

The war between Vlad and Mehmet continued to rage back and forth in Wallachia for ten years, but eventually, Vlad was killed, probably in battle against the Ottomans. His reputation for extreme cruelty has lasted into modern times, becoming the inspiration for the character of the Count in Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel Dracula.