It was in the beginning of a cold Autumn. The year was 1371. Near the village of Chernomen, two despots led their army against the Ottomans. They were two brothers – Uglesha and Vukashin. The Ottoman leader, Lala Shahi, would eventually rout his enemies. His victory was achieved after an early morning ambush. His men would slaughter the drunk and sleeping defenders. With this bloody success, the Ottomans would solidify their rule over the Balkans and liquidate any resistance eastwards of Niš.

Lala Shahin and the Ottoman Empire

By the end of 1364, the Ottoman empire is in reality separated in two. One part was Rumelie, where lies the capital of Erdine. The other was Anatolia – their lands in Asia Minor. The Ottoman Sultan, Murad I, was possibly busy with ruling the empire in Asia Minor. The other half of the empire is under the control of different military vicars called ghazi. Their primary leader was Lala Shahin. He was also the Sultan’s teacher. Lala Shahin was a talented general. Even though he had limited resources, he managed to solidify the Ottoman domain on the Balkans.

The Serbian Despots

After the death of Stephan Urosh in 1355, the Serbian kingdom began to decline. The vast territories in Macedonia and Greece were divided between different rulers from the central dynasty. Some of those considered themselves so independent from the main hierarchy that they called themselves kings. This was the case with the two brothers Vukashin and Uglesha. They both controlled territories in today’s Macedonia. Vukashin claimed to be “The king of all Serbians and Greeks” – in opposition to his brother.

The Background

After the Ottomans manage to destroy the rule of Momchil Voyvode in Thrace and the Rhodopes, they continued their expansion. Soon after the entire Thrace was under Ottoman rule, their ghazi began attacking the territories of the two Serbian despots. The two brothers, feeling the imminent threat of the Ottoman conquest, decided to gather an army. Their plan was to rout the attackers’ forces and chase them out of the territories in Rumelie.

After Gallipoli was taken in 1364 by Amadeo Savoy, there was a good chance for victory. The Ottoman position in the Balkans at that time was unstable. Bearing this in mind, the two brothers allied their forces and gathered all they needed to begin their march.

The Brothers’ Army – Reality and Numbers

In 1371 the army was ready. However, there is no hard evidence about the size of their army. It’s considered to be anywhere between 20,000 to 70,000. Based on the land they held and the tactis they employed, however, a smaller number is more likely.

The Ottoman force – Reality and Numbers

The Ottoman force for the battle was significantly smaller, but the exact number can again be debated. Their contemporary historical sources say they were no more than some 800 strong. We could possibly put their numbers at around half of what the Serbian alliance had.

The Real Difference in the Forces

The difference which decided the battle’s outcome was more the quality than the quantity. The entire Ottoman force consisted of seasoned warriors, who had survived numerous battles, sieges, and raids. On the contrary, the Serbian force consisted of an undisciplined rebel army and a small amount of cavalry.

Furthermore, it was logical that the Ottoman ghazis had superior experience. After all, they were in constant clashes with the resistance of the Balkan people. The Ottomans probably had a smaller but far better army.

Pre-battle Maneuvers

Confident in their bigger force, the two brothers began their march. They looked forward to expelling the Ottomans from Erdine and stopping their expansion. Their plan was to go down the stream of the river Maritsa and lead a surprise attack. Lala Shahin, however, knew what was going on. He also had extensive experience fighting in a rough terrain and organizing ambushes.

Considering his tactical advantage, he took measures in order to stop the Serbians’ advancement. The Ottoman leader sent trackers to scout the region. The Serbianswere overly confident, and never bothered to do that.

Thus, the Lala Shahin waited for the right moment to rout the marching rebels. His chance came in the early morning hours of the 26th of September. The Serbians had made their camp near the Maritsa, and had made one final crucial mistake. They decided to celebrate their future victory and held a feast. By the morning, the camp largely unguarded and many of the men were drunk.

Not a Battle but a Slaughter

The force of the Ottoman leader Lala Shahin entered the camp in the morning. His men took their knives out and began slaughtering their sleeping enemies. In the Massacre that followed the two Serbian leaders were mercilessly killed. Whoever did not die from the Ottoman blades drowned in the river of Maritsa, in an attempt to escape.

Outcome

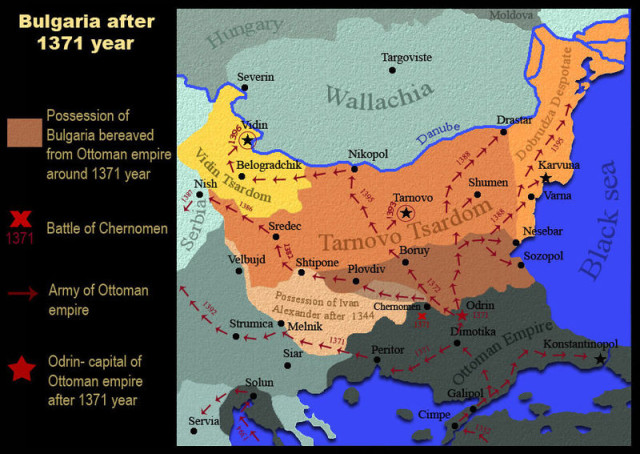

With a single bloody blow, the Serbian army was decimated. Lala Shahin’s victory liquidated any chances of the Macedonian despots to gather a new army. For something as simple as ego and alcohol, the fate of the Balkans was sealed. During the next decade and a half, the Ottomans would expand their territories on the Balkan Peninsula unhindered.

In 1387 the forces of the Ottoman leader Murad I would, at last, be defeated. The allied armies of Serbia and Bosnia would claim the victory. However, for Bulgaria, the Ottoman success on the Peninsula would mean a terrible and untimely threat. The events would open the borders for a forceful expansion and the Battle of Nicopolis, which in turn would result in five centuries of brutal slavery.

Bibliogrpahy:

- K.Irecheck, History of Bulgaria, 1978

- Gyuzelev and Petrov, Read on History of Bulgaria, II, Sofia, 1978

- Ducca, “History”; from Read on the History of the Middle Centuries, Bakalov and Angelov; Sofia, 1988