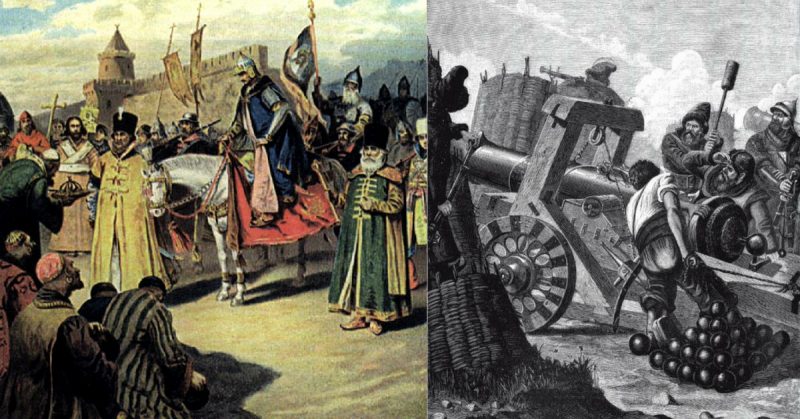

The army had been in place under the city walls for weeks. Ivan the Fourth, Tsar of all the Russians, accompanied his force in the field with the intention of seeing the sack of the city with his own eyes. The city was Kazan, the capital of a Khanate with an uneasy relationship with the Russian throne. There had been war and peace at intervals for decades, but Ivan had at last decided to crush the rebellious city-state of Kazan, and destroy its Tartar inhabitants.

The city was defended by 10,000 horsemen from the Mongol Nogai Hoard, who controlled a huge sprawling region of territory to the south of Kazan. Bound by ties of blood and of tradition, the Nogai horsemen had allied with the Kazan Khanate against the encroaching power of the expanding Russian state.

Ivan’s army had set out from Moscow in June of 1552. The army was huge, well equipped with artillery and light cavalry, though its main force was made up of the newly created Streltsy. These were heavily armed footsoldiers armed with muskets, sabres and the terrifying Bardiche, a massive pole-axe with a blade that could cleave a man in two with its sheer weight.

There were many tens of thousands of these men, dressed, drilled and armed identically, a sea of bright colours, blue, red, or green jackets and bright orange boots. They routed an advance force of Tartars from Kazan in August. By September the second, the siege was in place, and the gates of Kazan were shut.

Ivan had not yet gained his nickname ‘Grozny’, which roughly translates into English as ‘the Terrible.’ He was already an effective and determined ruler, but he was still only in his early twenties in 1552. His rule so far had, in fact, been one of relative peace and pragmatic domestic policy. Ivan had worked hard to get the huge and unwieldy economy in hand, with some success.

As the years passed he grew in stature and in terror, and became increasingly fierce and mentally unstable. His actions became more and more violent and his state of mind more unpredictable, and his wild eyes above his tangled beard became a source of terror for those who were in daily contact with him.

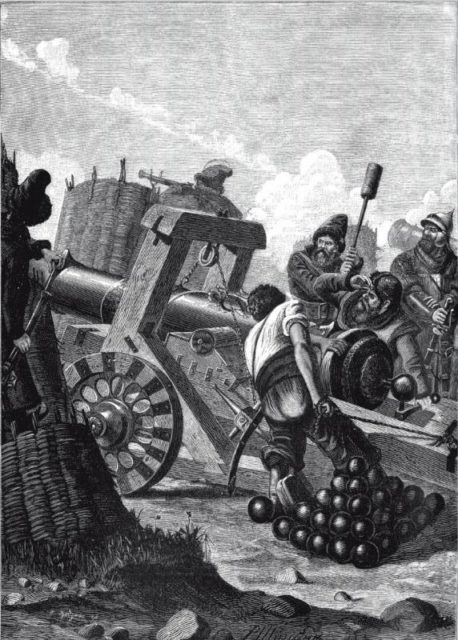

At Kazan, however, the future was still bright for Ivan, and he was well-liked and respected by his court and his staff. In mid-September, with the siege well established, he rode out one afternoon to inspect the completion of a great and innovative work. A battery tower had been built from wood, twelve meters high and many meters across. It was big enough to hold the entire artillery contingent of Ivan’s army and strong enough and flexible enough to withstand the recoil of the huge artillery pieces.

Kazan had been equipped with some old-fashioned cannon for the defence of the walls, but these had been silenced one by one over the previous weeks. Now Ivan’s cannon were being dragged and pushed up onto the new platform from which they could deliver massed volleys against the walls, over the heads of his own troops.

Underground there was another great feat of engineering taking place at Ivan’s command. Under the guidance of a most incongruous character, a little, twisted Englishman by the name of Butler, his teams of sappers had undermined the walls at several points, packing the tunnels with explosive. The man Butler was a consummate professional who took pride and care in his work. The result of this could be seen in his success, and in the fact that none of the tunnels had collapsed, nor had any of the sappers been killed.

Ivan was particularly pleased with Butler for his discovery of an underground stream which seemed to have been flowing to the city. This had been blown up and blocked, and now the water, which should have been flowing to feed the wells of Kazan was pooling into a dirty lake some way off. It pleased Ivan every time he looked at it.

It took a few days for the artillery to be moved onto the platform. Ivan waited patiently, eating and drinking and talking with his staff and his General, Alexander. In the city, the conditions were becoming worse and worse. The trapped civilians, the footsoldiers and the Mongol horsemen were feeling the inevitability of their approaching demise. Since the cannon on the walls had been silenced all was quiet, and the eyes of the people had a hollow, hunted look.

Underground the final touches were being put to the work of the sapper teams. Chambers were being packed with explosive right up to the foundations of the great city walls. These were connected up with an intricate network of smaller explosions, which should undermine the walls at many points, one after another. Butler examined each completed piece of work personally, complementing the teams with many extravagant phrases in his strange, heavily accented Russian.

The full complement of artillery was finally in place. The teams were well supplied with shot, and they were well trained. The Streltsy were deployed in formation facing the city wall. The sapper teams were withdrawn, and the men who would light the fuses and begin the destruction were waiting at the ends of their tunnels. Ivan withdrew to a small hillock nearby with his immediate staff. General Alexander would take direct command of the battle.

At last, the great assault began. The cannon fired in sequence from left to right, so that by the time the teams at the right were finished, the teams at the left had begun the sequence again. In this way, a constant barrage was achieved, and the force of the recoil against the platform was spread out. The engineer watched his construction with satisfaction. It worked excellently.

The cannon shot flew high above the heads of the infantry, and the supports beneath took the strain without incident. After a little time had elapsed the muffled thud of underground explosions was heard. The sapper teams had done their work. The cannons roared relentlessly, and suddenly a huge section of the wall disappeared in a cloud of flying masonry dust. There was an almighty crash, and the Russian cannons were stilled. Before the dust had settled the Streltsy were ordered forward, their vicious polearms raised.

There was no hope for the defenders. Starved and thirsty, the Mongol horsemen were unsuited to battle in the narrow streets of Kazan. They did not surrender, however, and only very few were taken prisoner. Though the defenders, soldier and civilian alike, fought to the death, countless Streltsy flowed in through the breach of the walls. The civilian population was massacred, many buildings were razed to the ground and Ivan the Fourth’s reputation for terror and brutality was begun. The battle marked the end of the Kazan Khanate, and though sporadic warfare continued in the region for some years afterward the city never again left Russian control.