The Knights Templar were the first and the most famous European warrior Order founded during the Crusades. From their bases in Europe and the Holy Land, they became a hugely influential political organization and fighting force.

They were also the first of these Orders to fall, becoming a legend.

Origins of the Templars

The Knights of the Temple were founded around 1115 by Hugue de Payens. There are several versions of the story, but all involve Hugue bringing together a small band of French knights to live a life of martial prowess and religious purity.

Taking vows like those of monks, they set out to escort pilgrims between Jerusalem, Jericho, and the site on the Jordan where Jesus was supposedly baptized.

The king and patriarch of Jerusalem, liking what they heard about the group, provided a base for their operations. It was the Al-Aqsa mosque, believed by Christians to be the site of the Temple of Solomon, from which the Order took their name.

Creating a Constant Crusade

The Knights Templar were an extension of the existing outlook of crusading knights. Only 1-2% of knights – Europe’s social, political, and military elite – went on crusade. Those who did took oaths to fight for religion. To encourage them, priests had developed an idea of holy war, in which fighting could save men from their sins instead of adding to them.

The Knights Templar took this to its logical conclusion. With their rigid rules and monastic lifestyle, they were warriors of God for life, not just the duration of a campaign.

In doing so, they shook off many aristocratic trappings. Fancy clothes, hair styles, and food were abandoned. At first, they lived lives of relative poverty. This was embodied in their most iconic image, which showed two knights sharing a single horse; supposedly all they could afford.

Still, they were among the wealthier European soldiers. With fine swords, metal armor, horses, and an unswerving dedication to duty, they quickly became an important tool of the Christian cause.

The Templars at War

In combat, the Templars were a hard-hitting force of heavy cavalry, often supported by their own infantry of lower status. Their rules forbade them from offering or receiving mercy from non-Christians. They were the most feared warriors in Christendom.

One of their first military actions was helping King Baldwin to suppress a rebellion at Antioch. In retrospect, this became symbolic of their situation. Fighting out of moral purpose was not as straight-forward as it might seem. They became drawn into Christendom’s internal politics.

They were most prominent in fighting against Islamic armies. In 1177, they were the heart of a charge that smashed Saladin’s army. The Templars’ own Grand Master, who led the charge, was captured. The Muslims were routed, bringing glory for the Templars.

Despite their skill and courage, the Templars were not always successful. A foolhardy charge saw many of them slaughtered by superior enemy numbers in 1187. It was also a Templar leader who led the Crusaders to disaster at Hattin.

As Muslim forces retook the Holy Land, the Templars took part in many desperate holding actions. They were prominent in the courageous but failed defense of Tripoli and Acre.

20,000 Templar knights and sergeants died between the Order’s founding and the loss of the Holy Land.

Growing Power

While this was going on, the Knights Templar were growing in power and wealth. Early in their existence, Hugues de Payens won the support of the Pope, and the influential monk Bernard of Clairvaux, together with many European aristocrats. Land all over Europe was donated to the Templars.

Eager young men flocked to join their ranks. Preceptories were set up in Apulia, Aquitaine, England, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Poitou, Provence, and Sicily. At these regional centers, new members were recruited and trained. Lands were managed and donations taken at the preceptories.

In the East, the Templars became among the greatest landowners in Syria. During their heyday, they had some of the strongest castles in the Holy Land. Ultimately, these were not enough to hold back their opponents.

Growing Responsibilities

With increasing power came growing responsibility.

The Templars were seen as moral leaders. Their example was held up to others. It also brought criticism from those who considered war and Christianity to be incompatible, or who were jealous and sought flaws in the Order.

As prominent warriors, the Templars were often given military leadership; leading to their greatest triumphs and their biggest disasters, as at Hattin.

Their wealth created an unexpected responsibility. In learning to manage their diverse holdings, they became experts in banking. Soon others were turning to them for financial services. Theirs was one of the most efficient and largest banking networks in medieval Europe.

Downfall, Suppression, and Remembrance

With the fall of Acre in 1291, the last Templar bastion in the Holy Land was lost. Crusading was at a low ebb, and the Templars were an Order bereft of a mission.

They were still wealthy and powerful acting as courtiers and administrators in governments across Europe. However, they were resented and vulnerable.

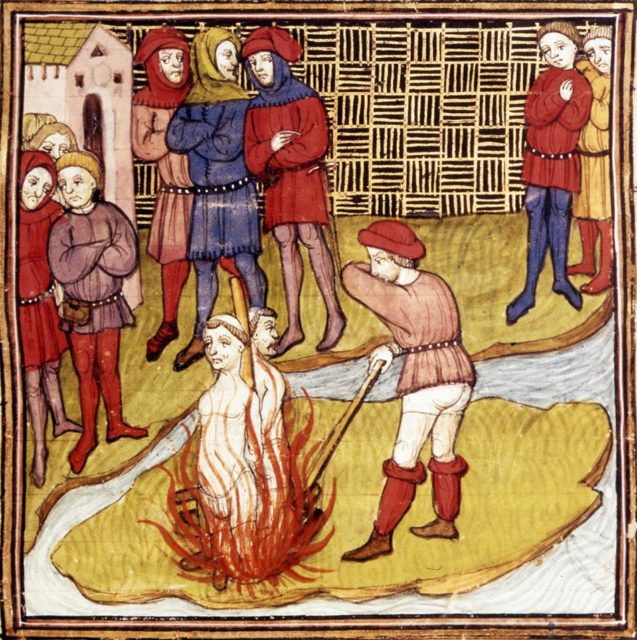

In the early 1300s, Esquiu de Floyrian, a renegade Templar, claimed that the Knights were guilty of sodomy, blasphemy, and idolatry. King Philip IV of France, seeing an opportunity to get rid of debts to the Templars and obtain their wealth, had them arrested throughout his country in 1307. Only 13 escaped. The rest were tortured, leading to numerous dubious confessions.

Given the confessions, the Pope could no longer back the Order. He had it suppressed. Within a few years, all the rulers of Europe had joined in quashing the Templars.

The dramatic origins, wars, and downfall of the Templars have ensured they are vividly remembered. Stories of adventure and conspiracy abound. None of these fictions are more extraordinary than the truth of a small band of knights who went from sharing a horse to leading Europe’s fight for dominance to finally being betrayed by one of their own.

Sources:

Alan Forey (1994), “The Military Orders, 1120-1312”, in Jonathan Riley-Smith, ed., The Oxford Illustrated History of the Crusades.

Andrew Holt (2016), “The New Knighthood”, in Medieval Warfare Vol VI issue 5.

Peter Konieczny (2016), “Who Were the Templars?”, in Medieval Warfare Vol VI issue 5.

Terence Wise and Richard Scollins (1984), The Knights of Christ.