Generally, people who study history don’t like to compare horrors. By engaging in debates about which war was the most costly, which epidemic killed the most victims, or which maniacal dictator killed the most people, one runs the risk of downplaying the suffering of the many millions of people involved.

Keeping that in mind, think about this: in the 14th and early 15th century, before the widespread use of gunpowder, the armies of one man were responsible for the deaths of perhaps 17 million people. These were murders committed with sword or fire.

Timur, or, as he is known in the West, Tamerlane (a Westernization of what he was called in Persian: “Timur-i-lang” or “Timur the Lame” due to the limp caused by a deep wound to his leg) was responsible for conquering more land while he lived than any other man in the pre-gunpowder era (with the exception of Alexander the Great). “Timur” means “iron.”

Timur was born into a tribe of mixed Turco-Mongol makeup in 1336 in today’s Uzbekistan (then known as “Transoxiana” in the West). Timur’s father was a minor noble in his tribe of Mongols, who had largely adopted the ways of the Turkish tribes of the steppes, though his son grew up surrounded by Islamic and Persian influences.

Like the Mongol Golden Horde and the other tribesmen of the steppes of Central Asia, Timur’s tribe engaged in nomadic herding. They also partook in small scale raiding of other tribes, which is how Timur received his wound.

He took an arrow in the leg and another in the arm. He is said to have lost two fingers and was not able to raise his right arm above his head for the rest of his life.

These injuries did not slow Timur down. By his early twenties, he had established a reputation as a fierce, crafty warrior and petty chieftain.

Timur, like many power-hungry people throughout history, was an opportunist. In 1357, he aligned himself with the enemies of Transoxiana, overthrew its khan, and took the throne with his ally, the khan of Moghulistan.

Timur waited for seven years to make his move. His brother-in-law entered into a feud with Timur’s co-ruler, and Timur, using family loyalty as an excuse, joined his brother-in-law Husayn to overthrow Timur’s partner on the throne.

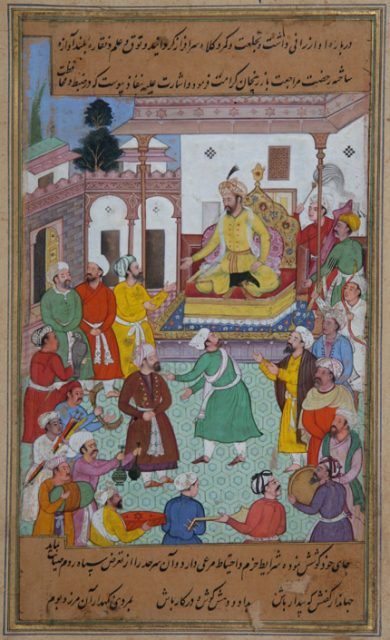

For a brief period, Timur and Husayn lived in harmony, but Husayn both refused to carry out Timur’s orders and alienated himself from the people in Balkh, Timur’s center of power. Apparently, the people of Balkh loved Timur who, according to most histories, treated them with respect and shared the spoils of his conquests with them.

Eventually, Timur had Husayn assassinated. What’s more, he married Husayn’s widow, a direct descendant of Genghis Khan. This enabled Timur to enlarge his growing army even further, as from this relationship he was able to rule as head of the Chagatay tribe, one of the most powerful of the Mongol tribes.

However, Timur never used the title of “Khan.” That was reserved for direct descendants of Genghis. Instead, he used the title of “Amir,” meaning general.

Timur saw it as his life’s mission to restore the glory and unity of the Mongol Empire, which had been split between Genghis Khan’s descendants after his death.

Though still powerful, the hey-day of the Mongol Empire was over by the time Timur rose to power. It was an empire in name only, fought over by various Mongol tribes, each claiming legitimacy.

Timur spent ten years conquering or subjugating the lands and tribes around him. Like Genghis Khan before him, Timur gave his rivals two choices: join with him and enjoy his protection, or oppose him and all traces of your existence would be removed from the face of the Earth.

This was not an idle threat. Cities would be razed. In some cases, salt would be sown in the earth so nothing would grow there for ages to come. Men, women, and children were killed. Some were taken into slavery.

His soldiers ran wild when instructed to – rape and torture were the order of the day. When the killing was over, the heads of the slain would be thrown onto a pile, making great mounds or pyramids to bear witness to what happened to those who opposed Timur.

Of course, some people were allowed to “escape,” as Timur knew that they would flee to the next city with tales of horror.

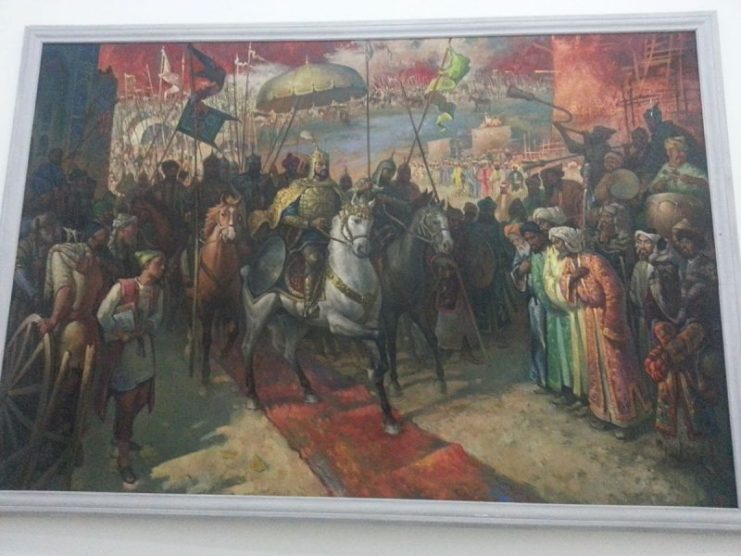

Some people were able to avoid slaughter: artisans, artists, and architects. They were taken in chains to Timur’s capital of Samarkand to beautify the city. It is said that, for a time, Samarkand was the most beautiful city in the world, an “Eighth Wonder of the World.”

Over the next 35 years, Timur conquered. It’s what he did. He once said: “There is but one God in the sky. There should be but one king on the Earth.” He also believed, like other conquerors, that his rule was approved by God – why or how else could he succeed?

From east to west, Timur’s empire expanded from Delhi in present-day India to Aleppo in Syria. The northern-most point of his empire lay on the northern parts of the Caspian and Aral Seas in Central Asia to Hormuz on the Persian Gulf.

All of present-day Iran, Iraq, half of Turkey, all of Afghanistan, Pakistan, and more were ruled by Timur. He even allied himself with enemies of the Ming Dynasty in China, in a vain attempt to conquer that vast empire.

Timur’s biggest challenge was the conquest of Persia. This country was one of the richest lands in the world in the 1300s and before. Its cities defied imagination with their advanced architecture, gardens, artwork, and central planning.

Luckily for Timur, as he was gaining in power, Persia was declining. Its lands and cities were being fought over by a variety of warlords, seemingly waiting for a strongman to come in and take advantage of their squabbling.

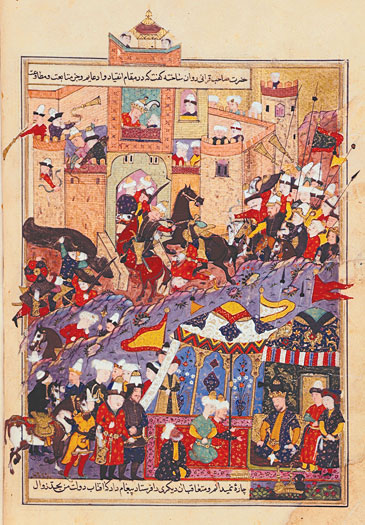

Timur started his campaign against the Persians in 1383, having already established control over some of its more remote border areas. Many cities, hearing of his cruelty, surrendered. Others did not.

One city that chose the latter option was Isfizar. When it was inevitably conquered, Timur decided that his prisoners should be added to the future defense of the city. How? They were cemented into the walls of the city – alive.

Though Timur had used terror tactics before his invasion of Persia, the prestige and population of that empire made his campaign there the most memorable, and horrifying.

The beautiful city of Isfahan wisely surrendered to Timur in 1387. A few years later, however, they made the mistake of rebelling against the heavy taxation of Timur. Outside the city gates, 28 towers of 1,500 heads each were erected.

This pattern repeated itself endlessly throughout Timur’s life. His campaign in Georgia virtually turned that kingdom into a wasteland for a time – he did this to use it as a buffer zone between the heart of his empire and the tribes of the Mongol Golden Horde to the north.

In the late 1390s, Timur targeted what is today India and Pakistan. His first stop was the city of Tulamba. It ceased to exist. Cleverly defeating an army of war elephants in front of the wealthy city of Delhi, Timur entered that city and killed 100,000 captives.

Timur was finally halted in western Turkey, more due to events in his empire than resistance. Timur’s reputation was so terrifying that Venetian and Genoese traders and naval vessels in the area actually helped Ottoman forces flee Timur’s armies.

Timur died in 1405. Like the Mongol khans before him, divided his empire between his living sons who proceeded to fight each other. Soon, the Timurid Empire began to decline and eventually disappear.