Some crusades were fought against fellow Christians. The Cathars, one of the inspirations behind Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code, were the targets of one of these crusades. Their dualist faith and resistance to papal authority led to their suppression in southern France, in a series of crusades that ran from 1209 to 1226, and that were as much about local politics as about faith.

Who Were the Cathars?

The Cathars were a group of dualistic Christians who lived mostly in southern France and northern Italy. Instead of believing in a single divine power they believed in two – one a force for good and the other for evil. The good God was that of the New Testament, concerned with matters of the spirit. The evil god was that of the Old Testament, sometimes associated with Satan, a god concerned with the physical world.

Among the other details of their beliefs, Cathars rejected marriage and many other Catholic sacraments. Though women were not entirely equal with men, they came far closer than elsewhere in Europe.

The Cause of Crusade

Any heretical sect, by its nature, rejected the Pope’s political as well as his spiritual authority. It was, therefore, important to the leaders of the Catholic church that the Cathars be brought to heel, for both moral and practical reasons.

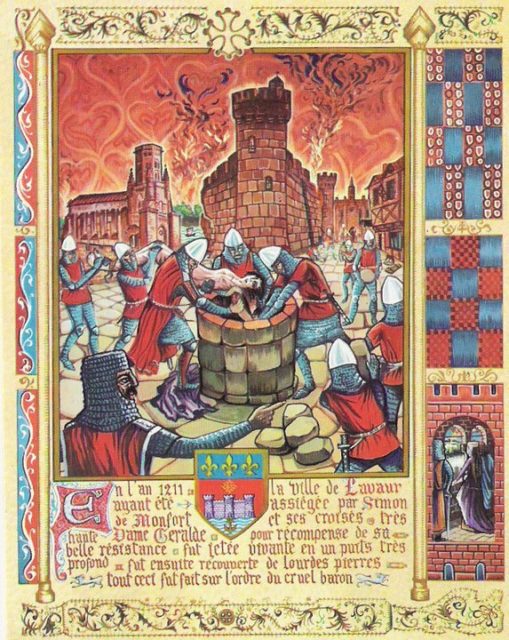

By 1200, Catharism had become popular in southern France, despite the attempts of various priests and papal emissaries to counter it. In January 1208, Pope Innocent III sent Pierre de Castelnau, a monk, lawyer, and theologian, to discuss the issue with Count Raymond VI of Toulouse, the most powerful local lord supporting the Cathars. Castelnau excommunicated Raymond for aiding heresy. On his way back to Rome, Castelnau was murdered, allegedly on Raymond’s orders.

In response, Innocent III called a crusade against Raymond and the Cathars.

Enter De Montfort

Seeing a force of angry knights and their followers coming his way, Raymond quickly came to terms. The crusade was redirected in 1210 against his neighbour, Raymond Roger of Trencavel. The town of Béziers was sacked and many of its citizens slaughtered, and Carcassonne surrendered rather than face such treatment.

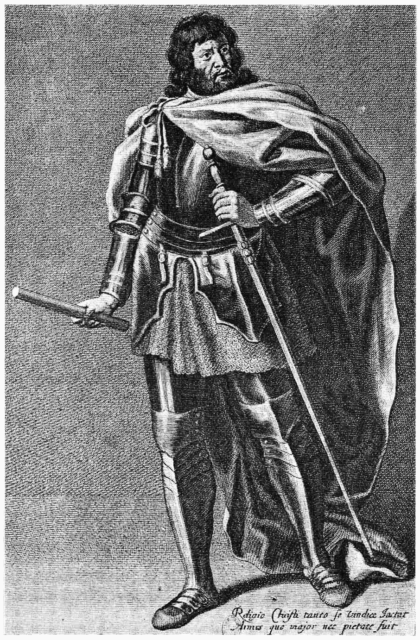

Simon de Montfort, a minor baron from northern France, was given the Trencavel lands. He set to subduing his new lands, facing stiff resistance from Lord Pierre-Roger of Cabaret, whose inaccessible castle gave him a safe base from which to harry the northerners.

The Siege of Termes – Showing Crusader Weaknesses and Strengths

The siege of Termes, which ran from August to November 1210, highlighted both the strengths and the weaknesses of de Montfort’s crusading armies.

Swiftly able to seize the outer defences of Termes, the crusaders then struggled to get further, as the castle was so high up the mountainous terrain that is was almost impossible to bombard with their catapults. In October, many crusaders left the siege, their vows fulfilled.

But de Montfort kept the siege going, undermining the walls. This forced the defenders to fight their way out and flee.

Toulouse and Castelnaudary

In the spring of 1211, fresh crusaders arrived, replenishing de Montfort’s force. Raymond of Toulouse’s failure to crush the heretics allowed them to lay siege to Toulouse. But the count had many armed followers, strong walls and plentiful supplies on his side. After two weeks, the crusaders withdrew.

Raymond went on the offensive. By now severely outnumbered, de Montfort blocked his route by holding the town of Castelnaudary. When Raymond, in turn, blocked the arrival of crusading reinforcements four miles away, de Montfort took a huge risk, sending half his cavalry to help the crusaders break through. As the battle turned against them, de Montfort himself galloped forth, turning the tide and breaking the siege of Castelnaudary.

Reinforcements and Success

De Montfort clung on by the thinnest of margins until 1212, when relief came once more. A crusade in Spain was being preached, and fervour for this campaign also brought men to southern France.

With growing numbers, de Montfort achieved a string of victories. The more towns he took, the more local barons shifted to his side, bringing men with them. By the end of the year, only Toulouse and Montauban held out against him.

Great Powers Intervene

Forces greater than himself became concerned that de Montfort would try to become Count of Toulouse. The kings of France, England, and Aragon, as well as the pope, all opposed this grab for power.

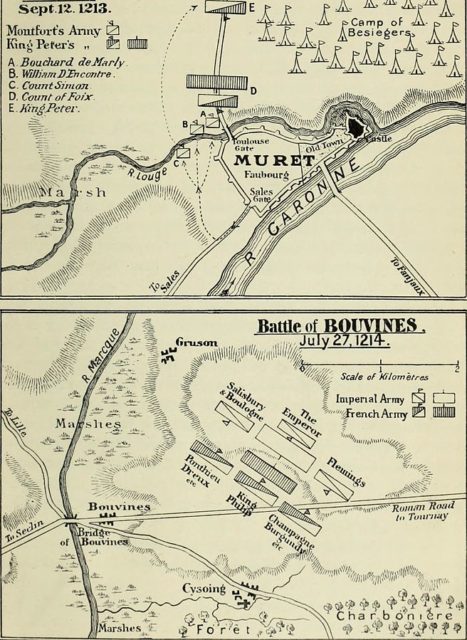

While Innocent III briefly suspended the crusade, King Peter of Aragon marched to attack de Montfort. Peter died at the Battle of Muret in September 1213, where de Montfort beat the invaders.

In April 1215, the French Prince Louis arrived with an army. Toulouse surrendered, and its defences were destroyed.

Cathar Comeback

In 1216, Raymond’s son began a fight back, with the support of the towns of Marseille, Avignon, and Tarascon. He captured Beaucaire while de Montfort was still gathering his troops.

The following year, Count Raymond returned and re-took Toulouse. De Montfort besieged the town but was held back by rebuilt fortifications.

After laying siege to Toulouse all winter, de Montfort launched assaults on the town in the spring and summer of 1218. On the 25th of June, a Toulousian force sallied forth against one of his siege shelters, and he rushed to join the fighting. Struck on the head by a trebuchet stone, de Montfort was killed.

Lacking his predecessor’s strength of will, Aumary de Montfort was unable to push on with the crusader advances. From 1218 to 1224, all the captured land was retaken.

Ending With a Whimper

Finally, in May 1226, King Louis VIII of France led a royal crusade south. He besieged Avignon and took the city. By now, the people of the region were tired of war, and they had lost the man who once inspired them. Raymond VII, his inheritor, could not muster a force to fend off Louis, and the region was conquered.

Like so many wars built on grand ideals, the Albigensian Crusades had become a matter of politics, and eventually ground to a halt amid the exhaustion of all those involved.

Sources:

Nicholas Hooper and Matthew Bennett (1996), The Cambridge Illustrated Atlas of Warfare: The Middle Ages 768-1487.