In 1212 a crusade was allegedly led by children in the hope of peacefully converting the Muslim population of the Middle East into Christianity, thus reclaiming the Holy Land. All information on this event must be taken with some reserve, for the reports differ and often include almost mythical elements. Some researchers have even cast doubt on the possibility of these events ever taking place at all, while others claim that the Crusade didn’t consist of children, but of the poor and homeless.

It proved quite difficult to determine the details of the crusade. There were two registered parallel movements that included a large number of juveniles and children that amassed around two leading figures ― Nicolas of Cologne from Germany and Stephen of Cloyes from France.

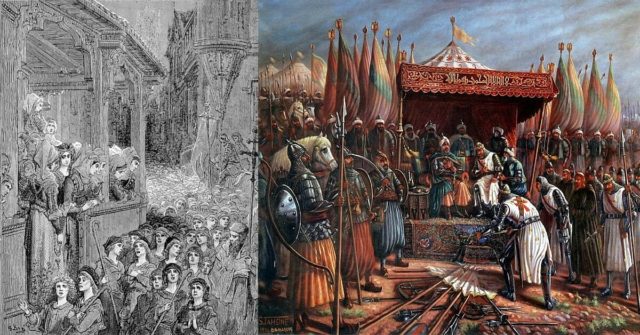

However, traditional verbal and written accounts had often merged the two movements into one, due to their similarity. Both of the boys were extremely eloquent, intelligent and charismatic. According to the European tradition, the story goes like this: A shepherd boy (an occupation that clearly invokes Christian iconography), either French or German, claimed that he had been visited by Jesus and trusted with the task of leading a non-violent crusade, converting Muslims to Christianity. His following grew as he proved he was God-sent, through a series of miracles. The number of followers is often put as around 30,000 children. He then led his followers to the Mediterranean Sea, for he expected an act of God to divide the sea, as he did for Moses. When the sea remained undivided, the boy’s followers began to disperse.

The traditional account also stated that the children were tricked by two merchants, called Hugh the Iron and William of Posquieres, who promised to take them across the Mediterranean to the Holy Land, but instead sold them into slavery in Tunisia. Some of the boys died of starvation or exhaustion and some died during a shipwreck that occurred off the coast of Sardinia, near the San Pietro island.

Modern research has concluded that there were, in fact, two organized movements that involved people of all ages in 1212, led by a French and a German boy. There are around 50 different sources that touch on the events, but only briefly. Some of them are written on a page or less, while other sources only mention the Crusade in a single sentence.

Stephen of Cloy

The account that involves the 12-year-old French shepherd, Stephen of Cloyes, begins with him bearing a letter for the king of France, sent by Jesus himself. People gathered around him, mostly youths and children, impressed by his leadership. He attracted others who also claimed to be miracle workers or possessed certain gifts that alluded they were also messengers from God. He continued to gather followers as he was headed to Saint-Denis, where he allegedly conducted a series of miracles that confirmed his status.

By that point, he had garnered a following of 30,000 adults and children.

Following the advice of the University of Paris, King Phillip II ordered the crowd to disperse. The king himself was hardly impressed, especially at the sight of a mere child leading the movement. He dismissed Stephen of Cloyes as a charlatan and refused to take him seriously. Stephen of Cloyes was so determined in his mission, however, that he started teaching at a local abbey, where his following continued to grow.

He then left Saint-Denis, in the hope of organizing a crusade. He traveled through all of the France spreading his message. Although he became known all over France, his following began to deteriorate, as not many were so enthusiastic about the crusade. The Church condemned the attempt, almost labeling it as heresy, but the population supported the young shepherd-turned-preacher. At the end of June 1212, Stephen led his largely juvenile Crusaders from Vendôme where he proclaimed the gathering point, to Marseilles were the promised miracle of dividing the sea was supposed to happen. They survived by begging for food, while the vast majority seem to have been disheartened by the hardship of this journey and returned to their families.

Nicholas of Cologne

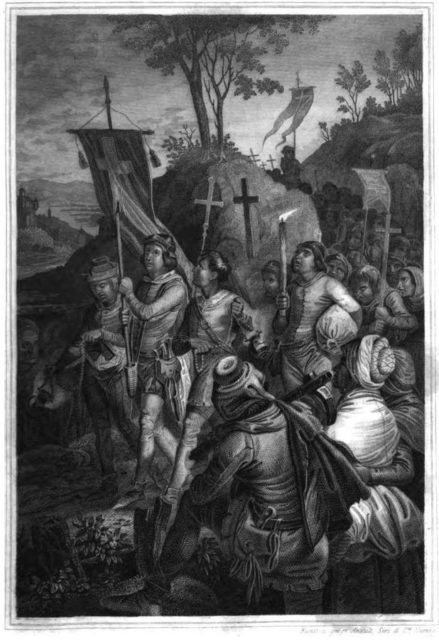

Just like his French counterpart, Nicholas was also a shepherd. He was from Rhineland, Germany. His teachings quickly garnered him a large following, as he was considered very eloquent and wise for a 12-year-old. Nicholas was perhaps the initiator of the idea that the sea would dry before the Crusaders in order for them to cross into the Holy Land. He insisted on a peaceful approach, which, in his vision, meant the converting of Muslims into Christianity. Instead of fighting the Saracens, he claimed that the Muslim kingdoms would be defeated when they converted. His disciples amassed in Cologne, eager to travel to the Middle East.

They were split into two groups, each taking a different route through Switzerland in order to reach the Italian coast. The pilgrimage led them across the Alps, which was an ordeal itself, as many had fallen victims to exhaustion during the trip. About 7,000 of them arrived in Genoa in late August 1212. They rushed to the harbor, waiting for the sea to divide before them. The crushing disappointment after realizing the miracle wasn’t going to happen caused many of them to abandon the Crusade.

Some felt betrayed by Nicholas and abandoned the quest immediately, while other sat in front of the calm sea, waiting for God to conduct his miracle, as they felt it was impossible for him not do so eventually. The city of Genoa offered citizenship to the pilgrims, as a reward for their faith and endurance.

Nicholas didn’t lose faith and he traveled to Pisa with what was left of his disciples. From there he continued with some of his most loyal followers to Vatican. The reports of this visit claim that Pope Innocent III welcomed them and treated them kindly. The Pope persuaded them to return home and quit the Crusade. Nicolas followed the advice and headed home, but didn’t survive the second crossing of the Alps. Some of his most loyal Crusaders continued to roam Europe, in hopes of reaching the Holy Land, but none of the reports claim that they managed to do so. Back in Germany, Nicolas’ father was lynched by an angry mob, who found his son responsible for the death of their children.

This story remains subject to further research and represents a part of the European medieval folklore tradition. Modern-day books and films had often related to the story about the “Army of the Innocents” and their ordeals.