Drugs were an integral part of the brainwashing process that the Assassins supposedly used to train young men to become single-minded, fanatical killers.

Everyone today knows what an assassin is and what one does, but relatively few people know where the word “assassin” comes from. The term was originally thought to be a corruption of an Arabic word that means “hashish smoker.” Recent research discovered it to have been derived from the term asasiyun which was originally used to describe a small sect of Shia Nizari Ismaili Muslims.

Despite lacking significant numbers, this sect nevertheless managed to exert considerable political influence in the Levant over a two hundred year period from 1090 to 1275. Famed and feared by Muslim and Crusader leaders alike, the Order of the Assassins managed to murder a great number of very important and powerful men in the two centuries in which they existed.

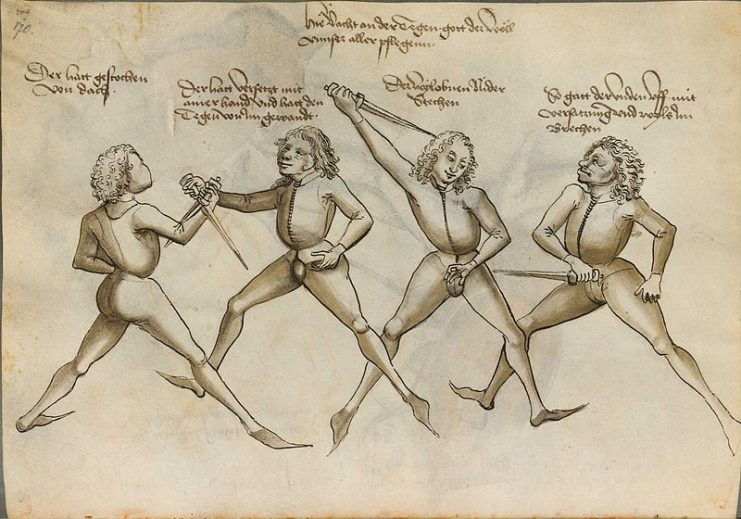

The killers they trained essentially shaped the modern conception of an expert assassin: a master of stealth, disguise and weaponry who is absolutely devoted to a singular goal, the elimination of his target. To achieve this he will spend months, sometimes years, painstakingly studying his mark and waiting for the perfect moment to strike.

The Order of the Assassins were not the first assassins in history. Assassins, in some shape or form, have existed as long as kings have been fighting wars. Also, the Order was not formed with the explicit aim of training and deploying assassins. The Nizari Ismaili Muslims were a minority within a minority in terms of their beliefs under the umbrella of Islam.

Some of their enemies later associated the name of their order with hashish, in reference to the legend that hashish and other drugs were an integral part of the brainwashing process that the Assassins supposedly used to train young men to become single-minded, fanatical killers.

The Order of the Assassins was, first and foremost, a religious order founded by an extremely devoted Ismaili Muslim named Hassan-i Sabbah. After surviving a terrible sickness that almost took his life as a young man, Hassan became passionately devoted to Ismailism and traveled all over the Levant, focusing his life on spreading its message – a relatively revolutionary one, rooted in ideals of egalitarianism and rejection of material wealth – and winning converts as a missionary.

As Ismailism was regarded as heresy by both Sunni and majority Shia Muslims though, this was dangerous work. Hassan quickly realized the need for stealth, traveling in disguise, and the eventual necessity of establishing a secure base for himself and his followers, where they would be both safe from persecution and able to strike at their enemies.

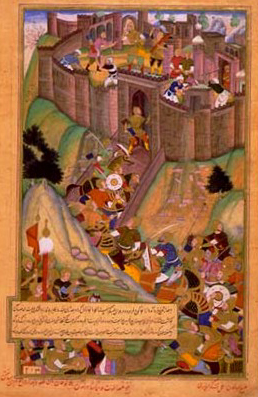

He found the ideal location at Alamut castle, high in the Alborz mountains in northern Iran, an imposing fortress perched on top of an 800-foot-high mountain. The only way up the near-vertical cliffs was a steep single track. Thus the fortress could be successfully defended by only a few men against an army.

It was perfect for Hassan’s purposes, but the problem was, of course, taking the castle, which was then under the control of a Seljuk commander.

To do this, in 1090 Hassan began infiltrating the garrison with missionaries, who covertly won over the soldiers with their message. Eventually, when a majority of the fortress’s soldiers had converted to Ismailism, Hassan marched in and declared the castle his.

The Seljuk commander of course thought this was a joke – until his own soldiers turned on him and announced their loyalty to Hassan. Hassan spared the commander’s life, and gave him a decent amount of gold before expelling him from the fortress.

This was the beginning of what was to eventually become an empire for the Order of the Assassins. Hassan and his followers took over a number of other mountain fortresses in the region like this, preferring to use cunning and stealthy missionary work rather than violence to achieve their aims. Later, of course, they would discover that violence and fear could be exceptionally useful tools in terms of exerting influence and growing power.

1092 was the year the Order carried out its first prominent assassination. Hassan identified Vizier Nizam al-Mulk as one of the biggest threats to the Order. He sent a particularly dedicated young follower on a mission to eliminate him.

The vizier was an extremely powerful man and was almost always surrounded by guards, so this would be no easy mission. The young assassin took his time, waiting for the end of the Ramadan fast. He disguised himself as a Sufi mystic, and said that he had an important message for the vizier. When the vizier agreed to see him, the message the young assassin gave was a fatal one, consisting of a hidden dagger slammed into his heart.

After the success of this mission, Hassan realized just how potent a weapon these assassins – which he called fidais – could be. He devised methods of training these young men that resulted in absolute devotion to their mission, unshakable focus and single-minded intent, and a ready willingness to die to achieve their aims.

He also realized that these men would need to be highly trained in a number of areas that would ensure the success of their missions: armed and unarmed combat, stealth, the ability to use effective disguises and go into deep cover, often for years and months, while obtaining the trust of their targets and those around them.

They would also – and this was a crucial factor – need to be readily willing to die if necessary. The methods Hassan (and later grand-masters of the Order, who were all referred to as The Old Man of the Mountain) used to inspire such fanatical devotion have been lost to the mists of history. Marco Polo, who supposedly visited Alamut Castle, claimed that it was through a brainwashing process.

According to Polo, young men – often orphans obtained for the specific purpose of becoming assassins – would be heavily drugged and taken to a lush garden full of beautiful women, and told that this was the paradise they would inhabit after death if they served faithfully. Of course, there is no evidence that this was actually done – but neither is there any evidence to suggest that such methods were not used.

The preferred weapon of the fidais was the dagger, and the method a fatal stabbing to the chest. To do this the fidai needed to get very close to the target, of course – and this in itself further stoked the fear that powerful men in the region were beginning to have of this mysterious sect.

This fear, and the growing reputation of the Assassins, were both useful as bargaining tools. Despite his realization of how useful his fidais were in achieving his political goals, Hassan preferred to use negotiation or bribery where possible, rather than killing. Sometimes a dagger placed on the pillow of a sleeping enemy at night was enough to frighten him into complying.

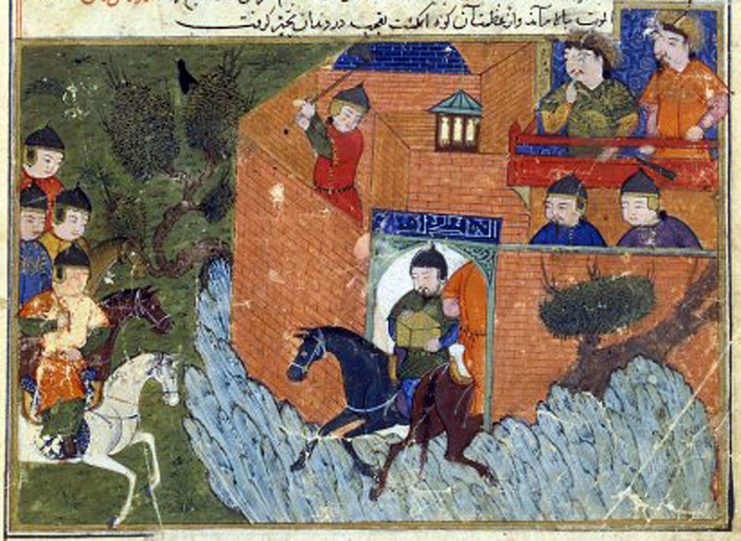

Over the next two hundred years the Old Men of the Mountain defended their religion and maintained their influence in the region by skilful political maneuvering – and by assassinating a great number of viziers, emirs and even Crusader princes. When Hulagu Khan arrived in the region in 1256, though, at the head of an enormous Mongol army, the Order was finished. Even they could not stand against so potent a power.

Read another story from us: The Remarkable History of the Original Assassins

The Order was essentially crushed after the Mongols eventually took all of their fortresses. Despite briefly taking control of Alamut again in 1275, they would never again exert influence in the region, and thereafter essentially died out – although the legends they inspired would live on for centuries.