When we think of the darkest, most bloody days of human history, our minds inevitably turn to the horrors of modern warfare. We think of battles like The Somme in WW1, or Stalingrad or Leningrad in WW2, or murderous regimes like Pol Pot’s or Hitler’s.

As bloody and brutal as these events were, they were often spread over periods of weeks, months, or years. Their huge death tolls accumulated over time.

However, when talking about the biggest loss of life through violence in a single day, the 13th of February 1258 surely ranks as one of the bloodiest days in human history. This was the day on which Hulagu Khan’s Mongol army entered Baghdad after a 12-day siege.

The city had approximately one million residents, and the army massacred many of them. It was a horrendous act that, in one fell swoop, brought an end to the Islamic Golden Age.

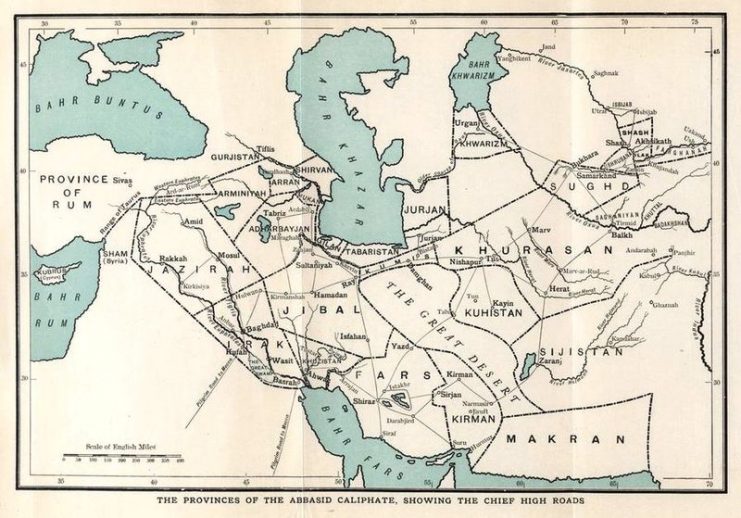

In the thirteenth century, Baghdad was not just the center of the Islamic world, it was, without a doubt, one of the greatest cities on earth. Since 751 AD, it had been the capital of the Abbasid Caliphate, an Islamic empire that ruled over most of the Middle East and much of North Africa.

While their political power had waned in the centuries leading up to that fateful day in 1258, the Abbasid caliphs nonetheless presided over perhaps the greatest empire of scholarship and knowledge the world had seen up to that point.

Baghdad was the physical locus of this cultural empire. The famous House of Wisdom was located there, a massive center of learning in which a vast array of scholars – both Islamic and non-Islamic – worked to translate all of the world’s wisdom and knowledge.

They translated work from all of the ancient empires across the globe into Arabic and recorded them in books which were stored in the city’s huge library.

Because of this emphasis on learning and knowledge, scholars of all races, religions, and nations were welcomed to Baghdad. They were paid handsomely for their contributions to its ever-expanding store of knowledge, in areas as diverse as astronomy, mathematics, science, philosophy, medicine, and chemistry.

Unfortunately, these halcyon days for scholarship were not to last.

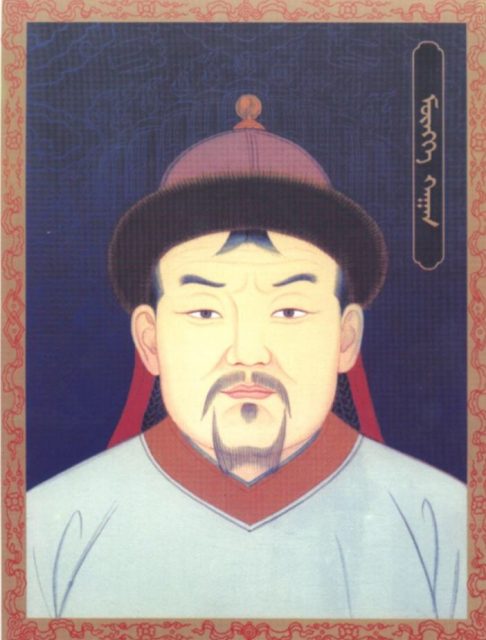

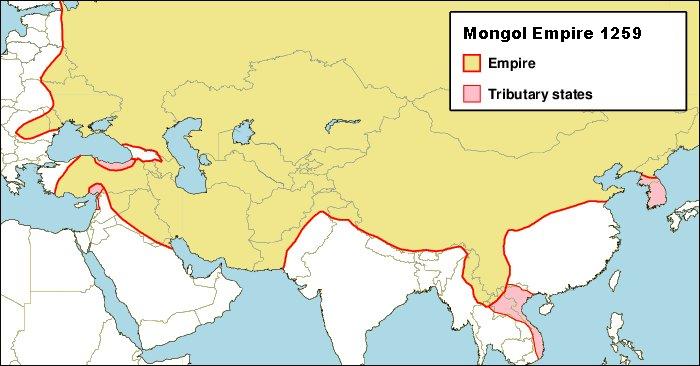

In 1258, the Mongol empire ruled a huge swathe of the Eurasian landmass. Presiding over this khaganate was one of Genghis Khan’s grandsons, Möngke, the fourth khagan of the Mongol empire.

His brother Kublai Khan would eventually become the fifth khagan. But Möngke chose another brother, Hulagu, to undertake the task of bringing the city of Baghdad under Mongol rule. It was part of Möngke’s plan to subjugate the entirety of Syria, Iran, and Mesopotamia.

For this mammoth task, a vast Mongol army was raised over the years before the campaign. One out of every ten men throughout the gigantic Mongol empire was conscripted into this army.

Historical estimates suggest this force ended up totaling anything from 100,000 to 150,000 soldiers, making it the largest Mongol army ever to have existed.

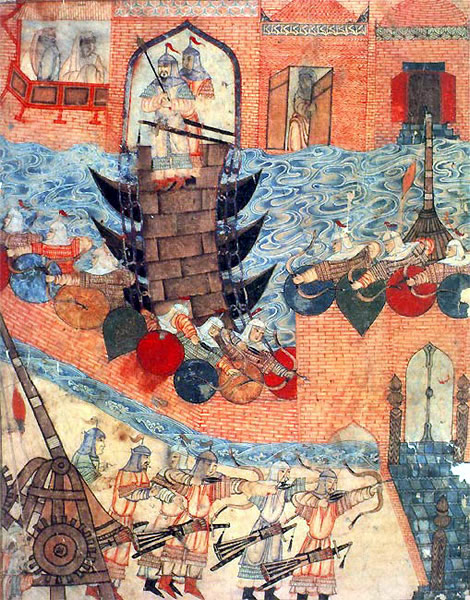

It was also supplemented by 20,000 Christian troops from Armenia and Antioch, along with 1,000 Chinese artillery engineers, and auxiliary contingents of Persian and Turkic soldiers.

This immense force first marched against a number of cities and rulers in Iran, which they crushed with ease. Hulagu also used his huge army to destroy the notorious Assassins, conquering their mountain fortress, Alamut, and executing the Grand Master of the Assassins, Rukn al-Dun Khurshah.

The Mongol army then began its advance toward Baghdad.

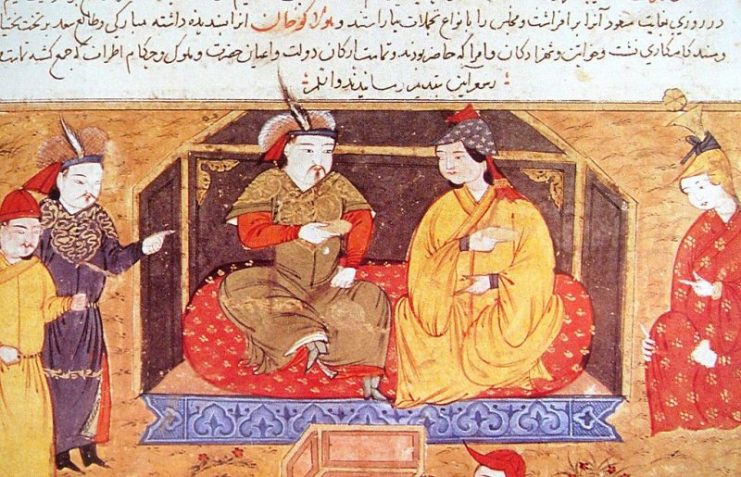

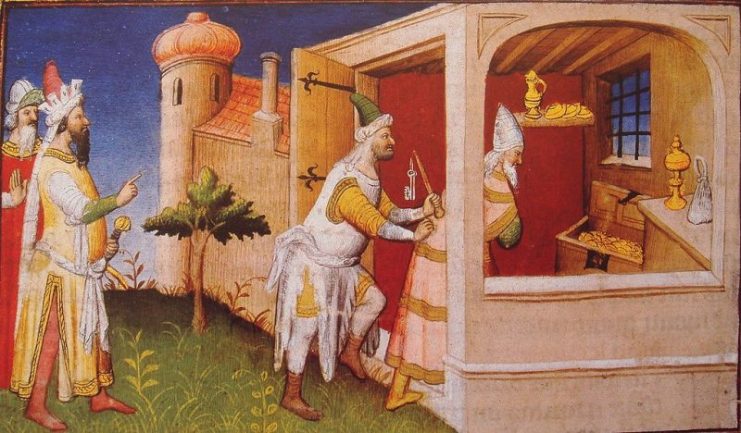

As was customary among Mongol military leaders when advancing on a city, Hulagu offered the ruler of Baghdad, Caliph Al-Musta’sim Billah, the chance to surrender his city to the Mongols without bloodshed.

Al-Musta’sim, for reasons which are still debated, refused Hulagu’s offer. Some historians theorize that he believed that the rest of the Islamic world would come to his aid if Baghdad was attacked.

However, others suggest that his grand vizier and most trusted advisor, Ibn al-Alkami, influenced his decision. Alkami convincing Al-Musta’sim to refuse either because of plain ignorance about the strength of the Mongol army or for darker and more treacherous motives.

Either way, Al-Musta’sim did not do nearly enough to prepare for the upcoming clash. He did little to reinforce Baghdad’s walls and did not call for reinforcements from neighboring emirs and Muslim emperors – many of whom he had made enemies of in any case.

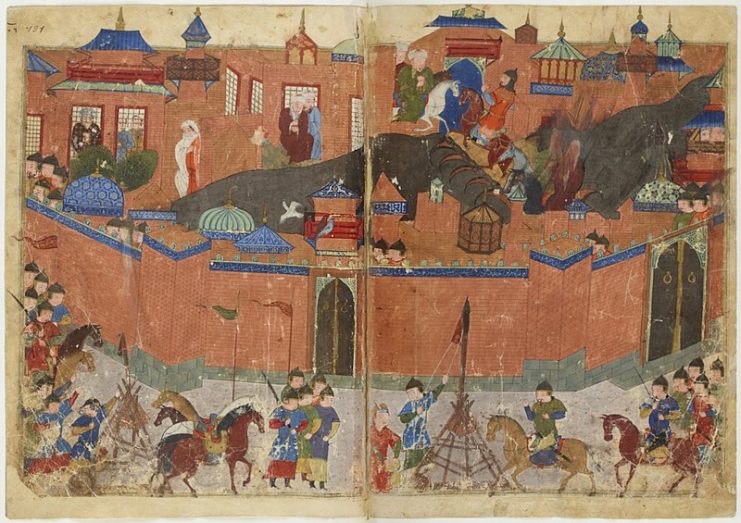

When Hulagu reached the city, he sent a number of Mongol columns to encircle the walls in a pincer movement. Al-Musta’sim responded by sending out a large force of cavalry, around 20,000 men, to meet the Mongols in open battle – a battle in which they were encircled and crushed by the far larger Mongol army.

Only then did Al-Musta’sim begin to realize the true hopelessness of his situation. Surrounded by the vast Mongol army, with his own army gone, there would be no escape.

While it was customary for Mongol military leaders to offer the chance for a bloodless surrender, it was always a one-off offer. If it was rejected the first time around, there would be no further chances to surrender — there would only be death and destruction.

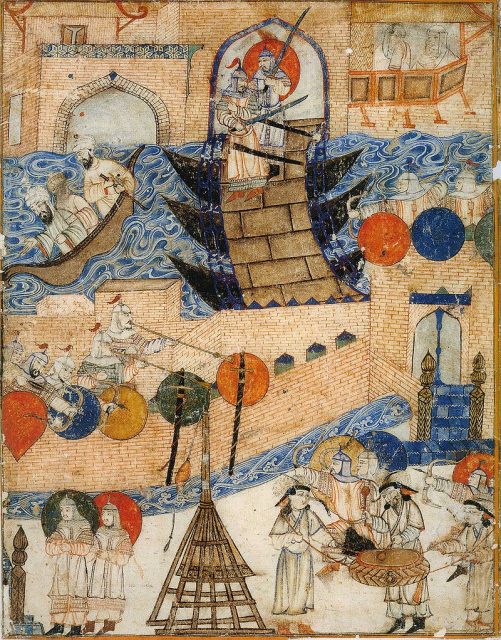

Hulagu’s troops began their siege of Baghdad on January 29th, 1258, with the combat engineers setting up their siege engines and beginning their attacks on the walls. By February 5th, most of the city’s defenses had been destroyed. It was obvious that the Mongols would soon take the city.

Now desperate, Al-Musta’sim attempted to negotiate with Hulagu, but his envoys were simply killed. Around 3,000 of Baghdad’s nobles also attempted to try and meet with Hulagu to offer terms of surrender, but he had them killed as well.

There was only one way this siege was going to end; Hulagu had long since made up his mind about this.

The city officially surrendered on February 10th, but Mongol troops only entered the city on February 13th. So began one of the bloodiest days the world has ever seen.

The city had about a million inhabitants, and none were allowed to escape. The only people who were spared were Baghdad’s population of Nestorian Christians. Hulagu’s mother was a Nestorian, and this is why he let them live.

As for the rest, the Mongol warriors put men, women, and children, old and young, to the sword. Those they did not kill they took as slaves. Al-Musta’sim was captured and forced to watch all of these horrendous mass killings, as well as the wanton destruction of what was surely one of the most beautiful cities on earth.

Palaces, mosques, churches, hospitals, and the city’s thirty-six public libraries were smashed to pieces or burned to the ground. The House of Wisdom, with its centuries of knowledge from all cultures across the planet, was razed.

The House’s collection of books – perhaps the largest collection of books in the world at that time – was also destroyed. The books were ripped apart and thrown into the Tigris River, which was said to have run black from the ink.

The Tigris was not only choked with destroyed books, but also with the bodies of the dead. The very lowest estimates state that 90,000 people were massacred when the Mongols entered the city – higher estimates range from the hundreds of thousands all the way up to a million.

As for Al-Musta’sim, once the city and its inhabitants had been utterly obliterated before his eyes – a task that took the vicious warriors the best part of a week – Hulagu killed the caliph’s entire family (aside from one son, who was sent to Mongolia, and a daughter whom Hulagu took as a concubine for his harem). Then Hulagu put the king to death as well.

Due to a Mongol decree against the spilling of royal blood on the earth, Al-Musta’sim was killed by being rolled up in a carpet and trampled to death inside it by horses.

Read another story from us: Six Years & a Pile of Bones- The Mongols Take a Chinese City

The complete destruction of Baghdad at the hands of the Mongols brought the Golden Age of Islam to a swift end. Indeed, some historians say that the sack of Baghdad was the single greatest blow ever struck against the Islamic World in such a short time.

After this, the Muslim world spiraled into a long period of disunity and decline. Without a doubt, February 13th, 1258, was one of the most destructive, bloody, and violent days in human history.