There are few military forces more infamous and renowned in history than the Mongolian armies of the 13th Century.

They swept through Asia and into Europe, conquering Russia and shattering resistance wherever they encountered it. Led by the grandsons of the great Genghis Khan, they combined tactical ingenuity with sheer strength of numbers. In fact, their reputation was so terrible that, as they advanced westwards, the warring kingdoms of Europe agreed to suspend all other conflicts, knowing that a unified front was their only hope of withstanding the invasion.

In the end, however, the Mongolian campaign in the west proved to be difficult. Their light cavalry, which had been a great asset in Asia, proved to be a weakness in the rain-soaked forests and muddy fields of Europe. Eventually the united forces of the continent managed to hold their ground, and when the leader of the Mongols fell ill and died, the invaders withdrew to select a successor.

Their new leader, Möngke Khan, had little interest in returning to Europe. Instead, he turned his attention to a new prize; the Middle East.

It took Möngke Khan five years to muster his full military might. When at last he was satisfied with his army, he selected his brother, Hulagu Khan, to head the Mongolian forces.

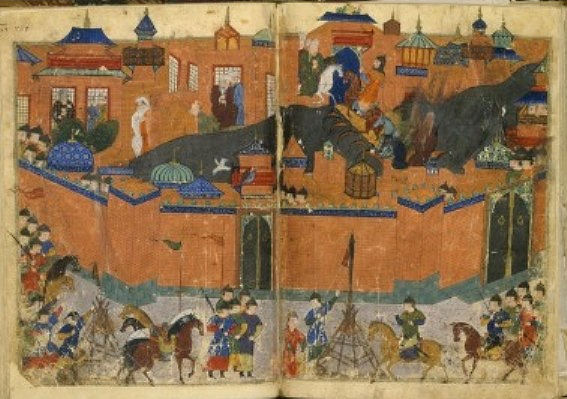

Instructing his brother to show mercy to those who surrendered, Möngke Khan unleashed his army. Many of the nations in their path submitted quickly and many, seeking to secure the safety of their people, offered their own soldiers to fight alongside the Mongols. In fact, by the time Hulagu reached Baghdad, he had a wide variety of nationalities at his back, even including a number of Frankish knights.

Persia, Baghdad, Damascus – the great powers of the Middle East fell before the Mongolian onslaught.

Those who would not surrender were brutally subdued, and the invaders seemed almost unstoppable.

With word of their conquests going before them, Hulagu sent envoys to Egypt. He was willing to accept their surrender, and his diplomats bore this message to Cairo, where Qutuz the Mamluk Sultan awaited them.

The Mongolian envoys outlined the merciless slaughter the Egyptians would face if they did not surrender. Of course, Qutuz’s councillors urged him to accept the Kahn’s terms and submit to the dominion of the Mongols.

Qutuz, on the other hand, chose a different course of action.

He had the envoys killed and displayed their severed heads above the city walls.

When word reached Hulagu of the Sultan’s deeds, he was incensed. He had gone out of his way to treat the envoys of his enemies with respect and courtesy, and the murder of his own was a monstrous affront. He readied his armies, outnumbering Qutuz’s forces ten to one, and prepared to march on Cairo.

It was then that the unexpected occurred.

Word reached Hulagu that his brother, Möngke Khan, had fallen ill. In fact, the leader of the Mongolian empire was close to death, and his successor would soon be chosen. Knowing that he was himself well placed to take his brother’s mantle, Hulagu withdraw, taking a large portion of his armies with him. He needed to return home and secure his title; Egypt would have to wait.

In his absence, he left one of his generals, Kitbuqa, in charge of a relatively small Mongolian force. The Sultan in Cairo, hearing that his enemy’s troops had been divided, wasted no time. Qutuz raised his own armies and set out to meet Kitbuqa head on.

With their forces now weakened considerably, the Mongols approached the Crusader armies that still lingered in the area, urging them to form an alliance against their common foe. At first the Christian troops were uncertain; the Mongolian invasion of Europe was not easily forgotten, much less forgiven, but the forces of Islam had been their enemy for centuries.

History might have taken a very different turn at this point. However, word from the Pope himself reached the Crusader leaders in Acre. By Papal decree, the armies of Christendom were not to aid the Mongols in any way.

In the end, the Crusaders elected to take a fairly neutral stance between the two factions. Remarkably, they even allowed the Sultan’s men safe passage through their lands, where they let the Egyptian army rest and replenish their supplies. Qutuz made full use of this advantage, before heading swiftly towards the remaining Mongolian troops.

The two armies finally met in the Jezreel Valley, near the spring of Ain Jalut. After a seemingly unstoppable advance, the Mongolian invasion faced a truly formidable match.

It was Kitbuqa who moved first. Qutuz had sent a smaller force out in advance, under the leadership of his ally, the Mamluk warrior Baibars. The majority of the Sultan’s army was hidden amongst woodland on the higher ground. Baibars knew the terrain well and is largely credited with planning the Egyptian strategy.

Attacking and then falling back, Baibars repeatedly withdrew his men from the field, retreating further and further from the Mongolian forces. A wiser man might have suspected a trap, but Kitbuqa threw caution to the wind and gave chase. When he reached the higher ground, Qutuz was waiting for him.

The full might of the Sultan’s army rushed from trees.

Kitbuqa and his men were surrounded on every side. They fought with ferocity to break out of the trap, but to no avail. Eventually, the Mongols’ left flank disintegrated, with men routing in a desperate attempt to flee.

Until now the Sultan himself had remained apart from the fighting, watching proceedings from a hill nearby, along with his own personal legion. When he saw the left flank breaking, however, he knew it was time to press the advantage. Ripping off his helmet, that his men might recognise their leader, he shouted,

“Oh, my Islam!”

Then he was moving forward, alone and headed for the heart of the battle. His men, seeing Qutuz himself bearing down upon the enemy, rallied behind the charge and stormed the broken side of the Mongolian army. In confusion and carnage, the once invincible Mongols turned and ran.

They were pursued, and any attempts at a counterattack were crushed. In the end, Kitbuqa himself was cut down. The Mongolian expansion into the Middle East was at an end.

The Battle of Ain Jalut proved to be one of the first times in history that a Mongolian army was defeated in close combat. After raiding and roaming unchecked across Asia, Europe and the Middle East, the descendants of Genghis Kahn had met their match.