The de Havilland Mosquito was one of Britains most iconic aircraft. The high-velocity airplane made entirely from plywood was landing severe blows on the Reich industry. The Germans realized that such a design needed to be copied and perhaps improved with the help of superior engineering.

The Mosquito was famous for its speed and the ability to evade AA fire. It was legendary for having a low rate of downed airplanes for the British. The loss rate within the RAF never fell bellow 5% of a squadron, while the Mosquitos would most often have zero or no casualties.

That was unacceptable for the Luftwaffe. The war was nearly over and the humiliation was becoming unbearable for the German aeronautical research departments. The Luftwaffe was in desperate need for night fighters, so a development of the Ta-154 began to brew in the Focke-Wulf factories in 1943.

The chief of the project was Kurt Tank, a leading figure in the Focke-Wulf company, and an innovative aircraft designer. Due to its similarity with the de Havilland model, the German prototype was named Moskito (German for Mosquito).

The aircraft combined a plywood hull bonded with a special phenolic resin adhesive called Tego film with the powerful Jumo 213 engine produced by the Junkers company. The only metal parts were the ones providing the frame to the pressurized cockpit.

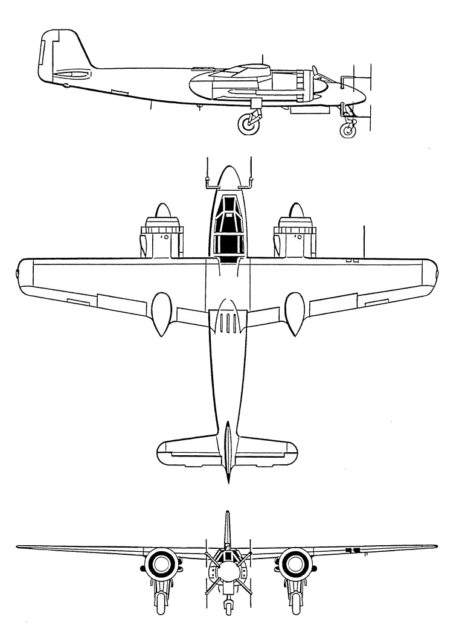

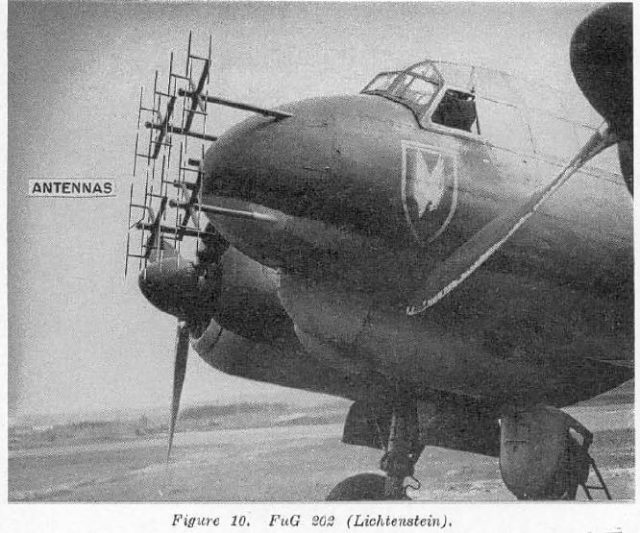

The German Moskito indeed proved successful on its flight tests, achieving speeds of 650 km, much like its British counterpart. It had a wingspan of 16.30 m (52 ft 5¼ in) and was 12.55 m (40 ft 3¼ in) leaving little space for its two-man crew. It relied on the FuG 212 C-1 Lichtenstein radar for night flying. The equipment slowed the plane, but it was invaluable as the technology offered night flying capabilities. The aircraft’s armament consisted of 2 × 20 mm MG 151 cannons, 2 × 30 mm (1.18 in) nose-mounted MK 108 cannons and 2 × fuselage-mounted 30 mm (1.18 in) MK 108 cannons, Schräge Musik.

Unfortunately for the Germans, mass production was interrupted for several reasons. First, the only factory making the revolutionary Tego Film glue was bombed by the Allies, so the plywood glue had to be replaced with a less reliable substitute. The test prototypes started to crash because of this defect.

In the meantime, the designers at Focke-Wulf were becoming more and more radical. Variants included a Mistel parasite fighter which was attached to the Moskito and a version that served as a cheap kamikaze-like flying bomb. It included a pilot that was supposed to bail out just before ramming his aircraft into an enemy bomber.

All these plans were interrupted by the rapid loss of territory in the final years of the war. The Red Army seized Focke-Wulf facilities near Poznan, Poland, where the main bulk of these experimental planes were being produced.

Although the Ta-154 project was ambitious and promising, the Heinkel lobby within the Luftwaffe overruled the Moskito and established the Heinkel He 219 as one of Germany’s primary night fighters.