On March 28th, 1800, a Scottish aristocrat took command of the small Brig-Sloop HMS Speedy, based at Port Mahon. The Scotsman, Thomas Cochrane, was an upstart, who had insulted or infuriated nearly every person he served under. He had even been court-martialed on his last voyage for disobedience.

In fact, Cochrane was most likely given the Speedy ,as a way of getting rid of him. His superiors hoped he would quietly fade away in the seemingly insignificant command. Cochrane, though, was determined to make a name for himself. He spent the next 14 months making the Speedy one of the most successful ships in the Mediterranean.

Cochrane came from a noble Scottish family, with a long history of military service. His uncle, Alexander Cochrane, was a Captain in the Royal Navy, and his influence helped to fast track Thomas’ career.

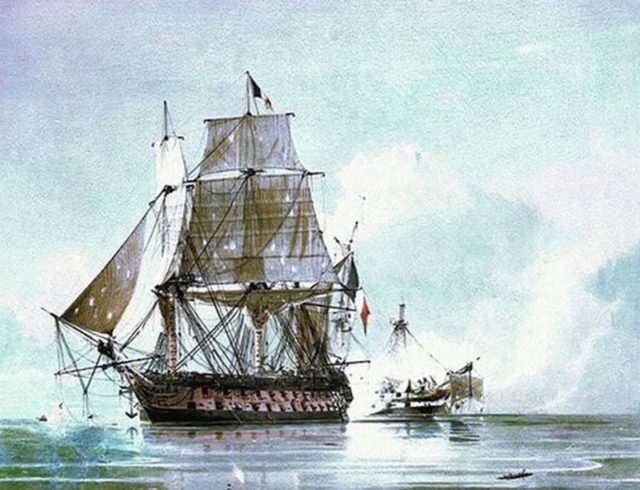

Joining the Navy in 1793 as a Midshipman, he served under his uncle on HMS Hind. Over the next 7 years, he would pass for Lieutenant, eventually landing himself a position aboard HMS Barfleur, under Lord Kieth, another Scottish noble and a family friend. His first big break came when Kieth gave him command of a prize ship, the 74-gun Genereux, which had recently been captured by the Barfleur. This assured Cochrane a promotion and command of his own ship.

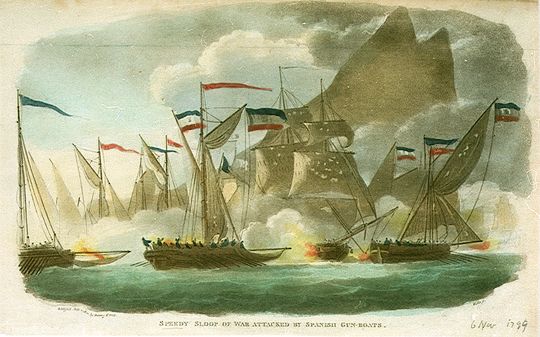

By the time he took command of her, Speedy had been in naval service for 11 years more than Cochrane and had the scars to prove it. She had recently been repaired following a battle with Spanish gunboats near Gibraltar, only the most recent of numerous actions.

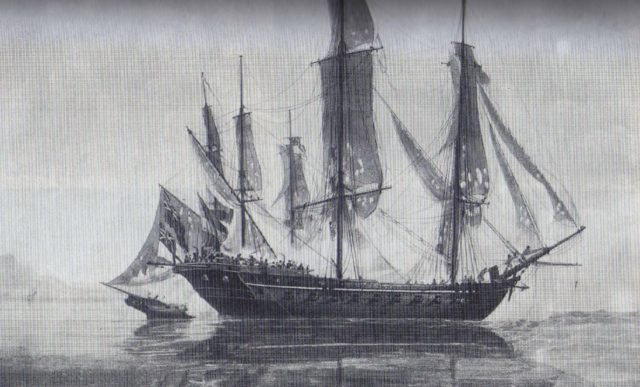

What is more, the ship was tiny compared to the other ships Cochrane had been on. He described her as “little more than a burlesque of a vessel of war.” His cabin was so small that there was barely enough room for more than his dining table, which also served as a work desk. It allowed only five feet of headroom. Cochrane would shave every morning by laying his water, brush, and soap on the quarterdeck, with his head coming through the skylight above his cabin.

As he became acquainted with the ship and her crew, he learned to respect them both. Within two days of taking command, Cochrane took Speedy out into open waters, to assist with convoy protection. By May 11th, 1800, he had taken his first prize, a small lateen-rigged French gunboat, which had been harassing his squadron.

Upon arriving in Leghorn (Livorno), in northern Italy, he was given free reign to raid and capture French shipping. No longer shackled to a slow-moving convoy, Cochrane was in his element. That summer he captured seven vessels, both French and Spanish. However, his success brought unwanted attention.

Enemy frigates began to keep a keen eye out for this small 14-gun brig which had been causing so much trouble. One nearly destroyed the small ship on December 21st, 1800. Speedy approached what appeared to be a Spanish merchant, sitting at anchor near the shore. As they drew near, however, the Spaniard’s gunports flew open, and her many cannons were run out, ready to fire. Cochrane, though, had a trick up his sleeve.

On hearing that the Spaniards were looking for him, he had disguised his ship as a Danish brig of similar size. When the larger, more powerful, Spaniard exposed herself as a warship, Cochrane ran up his Danish flag. But the Spaniard sent out a small boat to board Speedy.

Expecting this, Cochrane had hired a Danish quartermaster, and gave him the uniform of a Danish captain. When the Spanish boat approached, Speedy sent up a yellow signal flag, meaning she was under quarantine. The Danish quartermaster then explained to the Spaniards that plague had broken out onboard. Immediately the Spanish sailors turned about, and rowed back to their frigate. Cochrane had bet that their fear of the plague would overcome their lust for a prize. His bluff worked.

They evaded another frigate on March 19th, 1801. They were being pursued at night, by a larger, faster ship. All lights on Speedy were extinguished except one Cochrane ordered to flicker in his cabin occasionally. This gave the Spaniards something to follow, and they got used to chasing this occasional lone light.

Cochrane then had another lantern attached to a barrel, which was set to float behind Speedy. Finally, all lights were doused on the English ship, and the bobbing lantern gave an appearance similar to the occasional flicker from Cochrane’s cabin. The Spaniards took the bait, followed the barrel and Speedy changed course to escape.

However, both of these narrow escapes pale in comparison to his final encounter with a Spanish frigate.

Sitting off the Spanish coast, near Barcelona, they spotted a xebec-rigged frigate early in the morning of May 6th. She was the Gamo, with 32 guns, and 319 men; more than twice the guns, and five times the crew of the English brig. What is more, the Spanish guns were 8, 12, and 24 pounders, compared to Speedy’s 14 four-pounders.

Despite the differences, Speedy approached. At 9:30 the Spaniard fired a single cannon and hoisted her nation’s colors. Cochrane responded by raising the American flag. The ruse worked. The Spaniards were confused just long enough for the Speedy to get in close and pull along side.

Cochrane then ordered the English colors be raised. Realizing the strange little American brig was, in fact, the ship they had been hunting, the Spaniards opened fire. 16 cannons roared to life, sending balls of iron and lead flying towards the Englishmen.

None of them hit. Speedy was so small, and so close to the tall Gamo, that the balls simply flew overhead. Speedy’s guns, though, were in a perfect position to fire up towards the deck of the Spanish ship, whose crew had crowded on her top deck in order to board their prey.

The first blast of shot from Speedy killed the Spanish captain, and terrorized the crew. As the two ships closed, the Spaniards prepared to attempt a boarding, but before they leaped the gap onto his ship, Cochrane moved her just far enough away. She was unreachable but stayed close enough that they could sit comfortably below the shot of each broadside.

This was repeated two more times until Speedy’s rigging was completely destroyed.

Cochrane knew that he could not continue fighting this way, and told his men they could either board the enemy, or be boarded themselves. Every man from Speedy leapt forth from their small ship, leaving only the ship’s surgeon onboard, in charge of steering.

On Gamo, the English crew was met with an intense fight. Seeing that his men were being pushed back, and the Spanish flag was still flying, Cochrane ordered one of his sailors to take down the enemy’s colors. Again, his trickery worked! The Spanish crew assumed that the order to take down the colors had come from one of their own officers, and they surrendered.

The Gamo was captured with the loss of only three dead, and nine wounded. The Gamo’s crew suffered 14 dead, and 41 wounded, which exceeded the total number of crewmen onboard Speedy. Both ships were brought into Mahon, and Cochrane had ensured his promotion to Post Captain.

There are few moments in history when people are exactly where they were meant to be. Thomas Cochrane, in command of the brig-sloop HMS Speedy, is certainly an example of this. In his 14 months on board, he captured 53 ships, evaded destruction twice, and captured a Spanish ship with six times his weight in cannon shot, and five times his crew.

Cochrane’s reign of terror from Speedy was finally ended when he was captured by the French, who then often asked him for advice in future battles! Speedy was only the beginning of what would prove to be one of the most amazing careers in Royal Navy history.

Sources:

- Cochrane, Thomas. The Autobiography of a Seaman. United States: Nabu Press, 2010