It’s the infamous and destructive wars throughout each century of history that are responsible for so many of today’s technological advancements. Of course, along the way to the invention and perfection of modern weaponry, there were quite a few weapons that didn’t make their way into future warfare.

Such was the case of the Kaiten, a torpedo invented and used by Japan in the last months of World War II. However, it wasn’t technology or weaponry advancements that ended the Kaiten’s existence – it was the ultimate death of the soldiers who controlled the Kaiten.

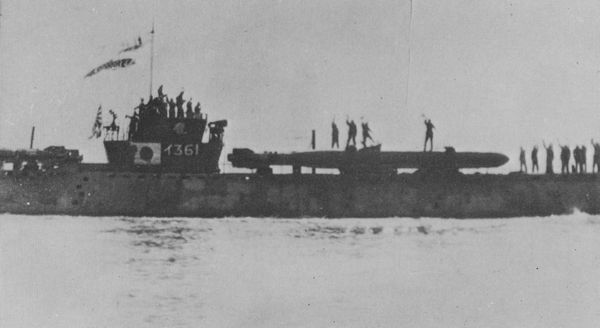

The Kaiten wasn’t like any other torpedo in use during World War II. These submarine torpedoes were manned by soldiers in the Imperial Japanese Navy, who drove these suicide craft right into their enemies. It was a weapon created to shake the enemy to their very core, its name chosen because it meant “the heaven shaker” or “the turn toward heaven” in English.

When the Japanese military felt they were losing control – and their chances of winning the war – they turned to the Kaiten, despite its high human price.

As 1943 came to a close, signaling yet another year of the second world war, the Japanese high command began exploring new options to secure victory for their troops. Military officials recommended using different types of suicide craft – Kamikaze planes, Kaiten submarine torpedoes, Shinyo boats, Fukuryu suicide divers, and even human mines were all options considered by the Imperial Japanese Navy.

Although initially rejected, the high command decided they were the best option for success in the first months of 1944, and the Japanese Special Attack Units began developing prototypes of the proposed human weapons. The first research on a potential Kaiten began in February 1944, and a prototype was developed by July 25 of that year.

The Kaiten submarine torpedo proved successful – in fact, it ranks second to Kamikaze planes in the effectiveness of Japanese suicide craft. Just one week after the first prototype was created, the Imperial Japanese Navy placed an order for 100 torpedoes. Those early Kaiten were simple, little more than a Type 93 torpedo engine connected to a cylinder in which the pilot would sit, directing it via limited electronics and steering.

Of course, in order to ensure the Kaiten could inflict damage, it required testing – and Lieutenants Hiroshi Kuroki and Sekio Nishina were the guinea pigs. Both knew they would die in the process, via either failure or success, like so many soldiers to come.

A total of six different models of Kaiten were designed, though five never saw combat. Initially, the first models were designed to eject their pilots once the torpedo began accelerating towards the final target; however, not a single test pilot attempted to escape, and it solidified its role as a suicide weapon.

In later models, the pilots were locked inside and unable to exit even if they desired – however, the pilots were given a self-destruct button, allowing them to kill themselves and the torpedo should their attack fail.

When the Kaiten finally entered the war after its brief test period, it quickly saw action. Pilots had its controls down: Kaiten would launch off of a host submarine, loaded with one pilot in each torpedo’s cockpit, aimed towards a specified target. Once in range of that target, the pilot brought the Kaiten to the surface, making any final adjustments necessary to make an impact.

Finally, the pilot and Kaiten submerged, warheads armed and ready as the torpedo sped into the enemy vessel. If a torpedo and its pilot failed, a second run would be attempted – if that, too, failed, the pilot then hit that self-destruct button.

Every man who entered a Kaiten torpedo knew that he would not leave it alive – and those who piloted the suicide weapon were young, aged 17 to 28. They were put through a dangerous, rigorous training program once chosen as a Kaiten pilot after passing an initial screening test and basic sailing training.

The next stages of training required potential pilots to perform circular runs to and from fixed landmarks, increasing the speed of their craft as the men progressed. Practice runs were filled with hazards, from rocks and underwater obstacles to suffocating depths. Pilot trainees were responsible for keeping track of their vessel, their target, and their oxygen levels.

With all of these compounded difficulties, not every soldier survived the program; as many as 15 died in training accidents. For those who survived, piloting a Kaiten meant saying final goodbyes to loved ones. Aware that their first mission would also be their last, pilots left messages, testaments, and other items behind for their families.

Kaiten pilots didn’t allow their imminent deaths to distract from their missions. They led their Kaiten to success, attacking U.S. naval ships, the U.S.S. Earl V. Johnson, and the U.S.S. Underhill. The attack on the Underhill was the most successful of all Kaiten launches.

On July 24, 1945, as the Underhill destroyer escorted U.S. supply and troop ships, six Kaiten carried by the I-53 submarine attacked its underside. The destroyer attempted to fight off the torpedoes and their parent submarine, but the Kaiten detonations ripped the Underhill in two. As it sank, the Underhill took its cargo and officers underwater with it.

However, the Kaiten wasn’t without flaws. Although it saw several successes, it was limited in range; the torpedo couldn’t survive deep dives, forcing any submarine carrying Kaiten to remain in relatively shallow waters. Because of this, as many as eight submarines were lost and more were damaged by the enemy.

Some Kaiten were spotted by the enemy, and others fell short of their mission, missing targets or failing to explode. By mid-August of 1945, all submarines were ordered home, taking the Kaiten back to Japan and ending its presence in war. World War II and the conflict with the U.S. ended just a week later.

Today, the Kaiten is memorialized by the Kaiten Memorial Museum on the island of Otsushima in Japan’s Inland Sea, the original site of all Kaiten pilots’ training. Though it has slipped into history since its final days in 1945, it’s a weapon that inflicted damage on both enemy naval forces and Japan’s own soldiers.

Faced with the possibility of losing an entire war, the Imperial Japanese Navy turned to the Kaiten – though it took the lives of its pilots, it brought explosive destruction to massive ships.

The Kaiten didn’t win the war for Japan, but it certainly left its own mark on World War II and the weaponry of the era.