The Horten Ho 229 is generally known by a few unique names. The plane was called the H.IX, by the Horten Brothers. The identity Ho 229 had been given to the plane by the German Ministry of Aviation. Sometimes, it was also called the Gotha Go 229, because Gothaer Waggonfabrik was the name of the German maker who manufactured the plane.

This plane has been recently called “Hitler’s Stealth fighter”, despite the fact that the plane’s stealth capacities may have been accidental. As per William Green, creator of “Warplanes of the Third Reich,” the Ho 229 was the principal “flying wing” air ship with a jet engine.

It was the primary plane with elements in its design which can be alluded to as stealth innovation, to obstruct the ability of radar to identify the plane.

The leader of the German Luftwaffe, Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, awarded the German aircraft machine industry what is called “3 X 1000” objective. Goring needed a plane that could transport 1000kg of bombs (2,200 lb), with a scope of 1000 km (620 miles) and speed of 1000 km/h (620 mph).

The Horten Brothers had been taking a shot at flying wing design lightweight gliders since the 1930’s. They thought that the low-drag of the gliders that were made previously could be the base for work that would meet Goring’s requests. The wings of the H.IX plane were produced using two carbon infused plywood boards, stuck to each other with sawdust and charcoal blend.

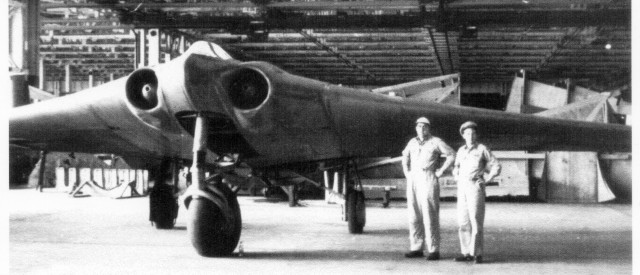

In 1943, 500,000 Reich Marks had been awarded to the Horten Brothers by Goring to assemble and fly a few models of the all-wing and jet-propelled Horten H IX. The Hortens flew an unpowered glider in March of 1944. The flying machine did not resemble any current plane being used in the Second World War.

It looked fundamentally the same as the cutting edge American B-2 Bomber. Goring was very much inspired with the plan and transferred it from the Hortens to the German aviation organization Gothaer Waggonfabrik.

At Gothaer, the plan experienced a few noteworthy upgrades. The outcome was a jet powered model, the H.IX V2, which was first flown on 2nd February, 1945.

Expelled from the venture, the Horten Brothers were working with the Horten H.XVIII, which was also known as the Amerika Bomber. The Horten H.XVIII was just an effort to satisfy the Germans wishes to manufacture an aircraft that could reach the United States. After a few more experimental flights, the Ho 229 was added to the German Jäger-Notprogramm, or Emergency Fighter Program, on 12th March, 1945.

Work on the next model rendition of the plane, the H.IX V3, finished when the American 3rd Army’s VII Corps came to the Gotha plant in Friederichsroda on 14th April, 1945.

In 2008, Northrop-Grumman, utilizing those designs plans which were available, fabricated a full-size generation of the H.IX V3 by using only those materials which were available in Germany in 1945. They studied the main surviving parts of a Ho 229 V3, which were accommodated at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum’s Paul E. Garber Restoration and Storage Facility on the outskirts of Washington DC in Suitland, Maryland.

Engineers at Northrop needed to see whether the German aircraft could really be resistant to radar. Northrop tried the non-flying reproduction at its classified radar testing office in Tejon, California. During the testing, the frequencies utilized by British radar offices toward the end of the war were directed towards the reproduction. Tom Dobrenz, a Northrop Grumman stealth master, said with regards to the H.IX, “This design gave them just about a 20% reduction in radar range detection over a conventional fighter of the day.”

When combined with the speed of the H.IX, after being picked up by British Homeland Defense radar, the Royal Air Force would have had only 8 minutes from the time of detecting the airplane before it approached England, rather than the standard 19 minutes.

While the design turned out to be stealthy, it has been contended that it was not intended to be stealthy. There is no written proof in Germany that the design was expected to be what would later be recognized as stealth innovation.

In an article composed by Reimar Horten, broadcast in the May 1950 version of the Argentine aviation magazine Revista Nacional de Aeronautica, Reimar composed, “…with the advent of radar, wood constructions, already considered antique, turned into something modern again. As the reflection of electric waves on metallic surfaces is good, such will be the image on the radar screen; on the contrary, on wood surfaces, that reflection is little, these resulting barely visible on the radar.”

In the late 1970s and beginning of the 1980s, data started to break to the media that the United States was doing some important work on airplanes with stealth innovation.

In 1983, Reimar Horten wrote in Nurflugel: Die Geschichte der Horten-Flugzeuge 1933-1960 (Herbert Weishaupt, 1983) that he had wanted to join a blend of sawdust, charcoal, and paste between the layers of wood that framed vast areas of the outside surface of the HIX wing to shield, he said, the “entire plane” from radar, in light of the fact that “the charcoal ought to ingest the electrical waves.

Under this shield the tubular steel, [airframe] and the engines, [would be] “undetectable” [to radar]” (p. 136, creator interpretation).

By 1983, the fundamental elements of American stealth innovation were at the point of being public knowledge.

After the war, the latest scientific improvements prompted the idea of planning an airframe that could sidestep radar. It was found that a jet-powered, flying wing design, just like the Horten Ho 229 will have a little radar cross-area to traditional contemporary twin-motor aircraft. This is because the wings were merged into the fuselage and there were no extensive propeller disks or vertical and horizontal tail surfaces to give a locatable radar signature.

Reimar Horten said he blended charcoal dust with the wood paste to soak up electromagnetic waves (radar), which he accepted could shield the aircraft from identification by British early warning ground-based radar that worked at 20 to 30 MHz (the top end of the HF band), which is called Chain Home radar.

Engineers of the Northrop-Grumman Corporation had a great interest on the Ho 229, and a few of them went to the Smithsonian Museum’s office in Silver Hill, Maryland in the 1980s to learn about and study the V3 airframe. A group of engineers from Northrop-Grumman did some electromagnetic experimentation the V3’s multilayer wooden middle-area nose cones.

The cones are 3/4 of an inch (19 mm) thick and made up of thin sheets of veneer. The group inferred that there was surely some type of conducting element within the paste, as the radar signal lessened extensively as it passed through the cone.

So it turns out Hitler was far along with developing a plane that was far ahead of its time!

The Horten Ho 229 being restored at Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center (Credits: Cynrik de Decker)