The United States went “all in” on the Norden bombsight before the Second World War, subsequently doubling down on it and its variations during the conflict. A crucial element of the US Army Air Forces’ (USAAF) daylight bombing campaigns over German-held territory in Europe, but was it as great a tool as the Americans hoped it would be?

Developing better technologies for aerial bombardments

During the interwar period, nations worked tirelessly to develop technologies that could better utilize aerial bombardments to destroy – or, at least, limit – another country’s ability to spark a war. The United States was no different. It sought to think up technology that would reduce the exposure of ground forces to enemy combatants.

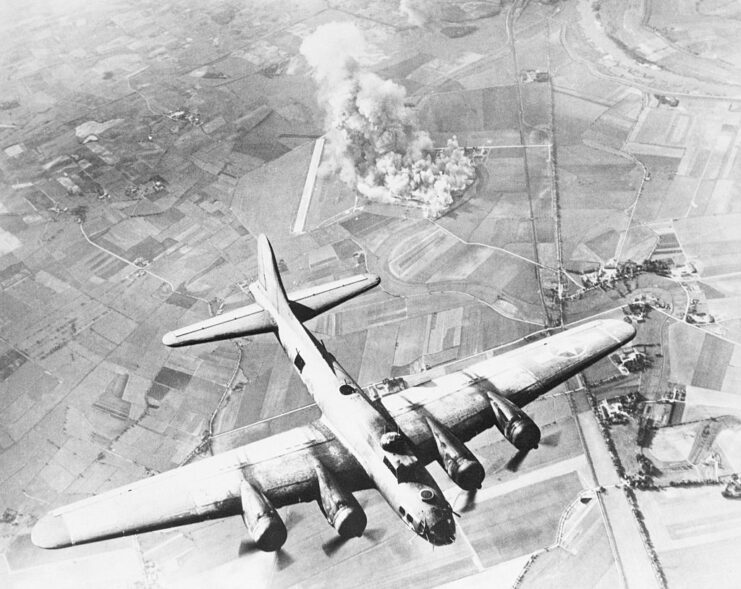

The idea was simple: destroy large formations, capital ships and industry before they could engage, therefore reducing casualties. This was no easy feat, however, as a typical bomber at 20,000 feet would need to drop its load accurately, roughly two and a half miles before it reached its target. It would also be past the area by the time the bombs hit the target.

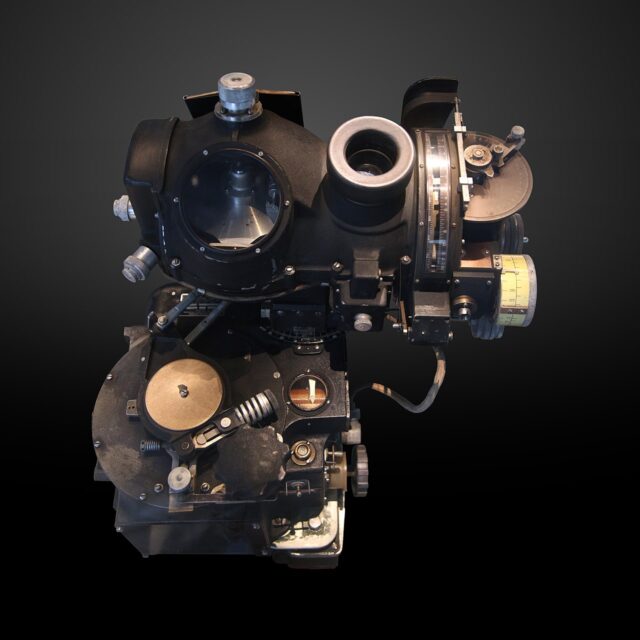

The US Navy’s prayers were answered when a group of engineers, led by Carl Norden, developed a bombsight he once claimed “could put a bomb in a pickle barrel from 20,000 feet.” The US Army Air Corps (USAAC) followed the Navy’s lead, and the two services combined funds to develop and produce the Norden bombsight.

A sum of $1.1 billion was spent on the concept by the end of the Second World War.

To put the project’s importance and expense in perspective, consider the US spent $2.2 billion on the Manhattan Project to work on the world’s first atomic bomb. We know the results of the latter, but just how effective was the “cutting edge” technology of the Norden bombsight, and did it accomplish what it was tasked with achieving?

Your mission, if you choose to accept it

The development of the Norden bombsight and the technology involved was kept secret. Tens of thousands of the devices were produced for the US military, with the intention being to solve four key issues.

Firstly, the Norden bombsight was to assist the US armed forces in reducing an enemy’s capability for war through precision bombing. Such missions would incorporate large, fast bombers conducting daylight attacks on both industrial structures and transportation infrastructure. Second, the technology was intended to enable naval and aerial forces to accurately bomb enemy formations, to incapacitate these forces before they could bring their weapons to bear on American servicemen.

Thirdly, the Norden bombsight had to work in combat conditions while being operated by a pilot or a bombardier who’d been trained on what was essentially an analog computer. Lastly, the device’s pinpoint accuracy was packaged to both the US Congress and the public at large as a means of reducing or eliminating all collateral damage to civilians and other unintended targets.

Every effort was made to keep the particulars of the Norden bombsight secret during development, production and combat use, even from American allies. Bombardiers gave an oath not to reveal how the device worked if captured by the enemy.

Performance of the Norden bombsight – Big bucks, but no bang!

Many studies and much analysis have been done into the effectiveness of the Allied bombing campaign during World War II. It has been debated whether the number of resources allocated to the campaign combined with the loss of life (both aircrews and enemy casualties) and the accuracy of the attacks justified the effort and expense expended.

The US Air Force, as it became known after the war, has given probably the most favorable reviews of the campaign. An official audit carried out after the conflict concluded that, concerning the Eighth Air Force, 31.8 percent of bombs from 21,000 feet hit within 1,000 feet of their target.

This was the most optimistic assessment. Others had a hit ratio as low as five percent.

Malcolm Gladwell, during a 2011 TED Talk, discussed data from a 22-mission campaign on a chemical factory in Germany that revealed only 10 percent of 85,000 bombs hit their target. What’s more, only 40 percent of that total detonated. The raids he speaks of occurred in 1944, meaning they involved experienced crews and bombardiers, and the target wasn’t small, at 757 acres. The results: the factory was back in business in a matter of weeks.

Considering how the Norden bombsight addressed the first problem facing it, we have to ask: was the Allied bombing campaign able to eliminate Germany’s ability to stay in the war? Quite simply, no. Most research suggests that it was actually the country’s lack of natural resources and manpower that played a much greater part.

Was the Norden bombsight as accurate as people claim?

To answer the second requirement is a much easier task. The Norden bombsight was abandoned by the US Navy early on, in favor of the dive and torpedo bombing of enemy ships. The reason: accuracy.

The US Army was no different when it came to attacking enemy ground forces. It relied heavily on fighter-bombers to provide accurate fire support, and these aircraft weren’t fitted with Norden bombsights. Instead, these pilots used dive-bombing and strafing attacks. Even on D-Day, against static beach emplacements, the majority of pre-invasion bombers missed their targets completely, leaving the fortifications intact for the amphibious and naval forces to deal with.

A 2009 thesis written by Michael Tremblay points out a telling quote from a pilot who described an in-flight emergency during the conflict. “I ordered the crew to dump everything overboard. All the ammunition, machine guns, even the Norden Bombsight which Lieutenant Fitzsimmons took a great deal of pleasure tossing out,” the airman is reported as saying.

The willingness and pleasure of the crew in throwing out the Norden is very telling of the lack of respect for its value, despite its super secret nature.

What about in typical combat conditions?

Was the Norden bombsight able to function properly in typical combat conditions? Also a resounding no. Despite the extensive training of over 50,000 bombardiers, the biggest problems with the device had little to do with the airmen themselves.

The device was designed so the bombardier could manually line up the target in the bombsight and let the Norden take over the calculations. However, they needed to see said target first. Anyone familiar with Europe knows that daylight doesn’t necessarily mean sunlight. Clouds are more common than not and, consequently, crews couldn’t always precisely locate their targets.

Additionally, they were flying at higher altitudes, faster speeds, and in the face of enemy flak and fighters. The Norden bombsight required constant speed and heading to be effective, but that also made the bombers susceptible to the enemy.

Finally, there were instances where the bombsight didn’t work properly even under good conditions. The main reason for this was that mass production meant sub-contractors had to be used to meet the demand, leading to countless production errors.

Germany knew about the Norden bombsight

The last stipulation in the development and production of the Norden bombsight was the secrecy of the project. Yet again, the project failed in this respect.

Germany already had plans for a bombsight over two years before the United States entered WWII. A German man working for Carl Norden copied the plans and specs and sent them to Germany, where he later vacationed and explained the inner workings of the device.

More from us: Tupolev Tu-95: The Soviet-Era Bomber That Could See Nearly 100 Years of Active Service

Ironically, the Luftwaffe decided the device wasn’t practical for its purposes. It was too complicated for the user, had too many small moving parts to be produced in quantity and was seemingly no more accurate than Germany’s own bombsights.