Joining the US Army Air Forces (USAAF)

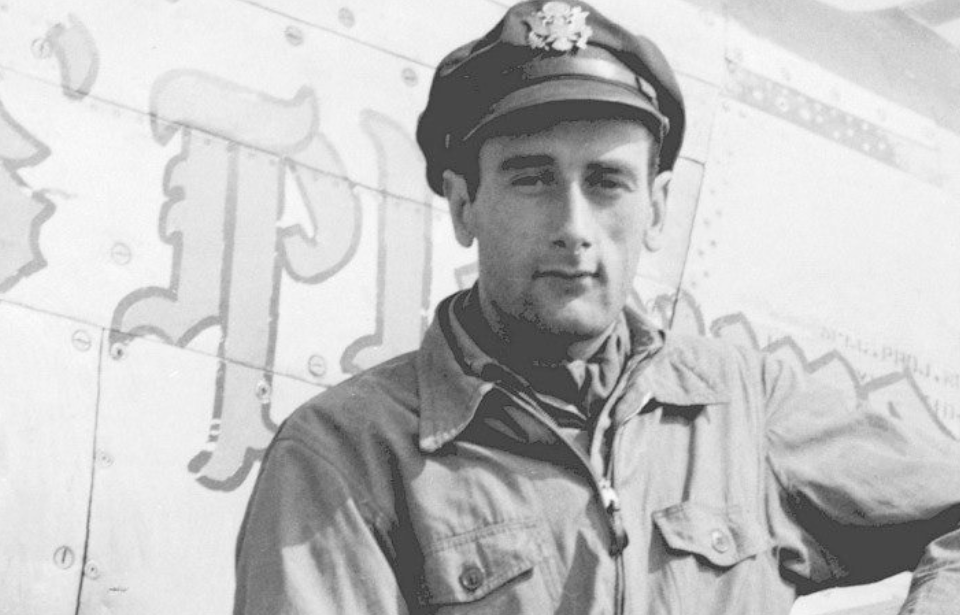

Born in New York, Bruce Carr was just 15 years old when the Second World War broke out in 1939. Motivated by the events of that year, the teenager made a firm commitment to master the art of flying.

Jump ahead three years to September 3, 1942, and Carr, now 18, enthusiastically enlisted in the US Army Air Forces. Using his prior aviation experience, he joined the service’s accelerated training program, ascending into the skies aboard the Curtiss P-40 Warhawk.

On August 30, 1943, Carr attained the rank of flight officer, amassing an impressive 240 flight hours. His expertise extended to specialized training, enabling him to pilot both the North American P-51 Mustang and A-36 Apache. The former, in particular, held a special place in his heart, earning the endearing nickname, Angels’ Playmate.

He didn’t get credit for his first aerial victory

In 1944, Carr was stationed in England with the 380th Fighter Squadron, 363rd Fighter Group, Ninth Air Force at RAF Rivenhall. His first major combat achievement came after a fierce pursuit and exchange of gunfire, resulting in the downing of a Messerschmitt Bf 109. However, he did not receive official acknowledgment since it did not meet the specific criteria for a confirmed kill.

His bold and assertive approach distinguished him as a unique pilot, although his superiors frequently criticized him for being “overaggressive.” As a result, he was reassigned to the 353rd Squadron, 354th Fighter Group, stationed at RAF Lashenden.

A trip to Germany

On November 2, 1944, Bruce Carr tragically lost of his beloved P-51D. While leading a strafing mission over a German airfield in Czechoslovakia, he faced the grim reality that his aircraft was on the verge of failure and made the decision to eject deep within enemy lines.

Remarkably, he managed to evade capture for several days, showing his resourcefulness and resolve in challenging conditions.

Despite successfully avoiding capture, Carr faced the difficult challenges of going without food or water, leading him to consider surrender. Aware of a nearby airfield, he set out with the intention of giving himself up.

When he arrived, he saw a crew preparing a German Focke-Wulf Fw 190 for takeoff. Shifting his plan, Carr decided to wait until the crew left before stealthily boarding the aircraft.

Traveling home

Carr dedicated himself to mastering the complexities of the Fw 190, undeterred by the challenge of deciphering the German labels and instructions. His hard work paid off. When the moment came, he took off without a hitch, avoiding any conflicts or unnecessary attention.

Leaving German airspace was relatively straightforward, thanks to the aircraft’s German insignia. However, re-entering Allied territory in France proved to be more difficult. Almost immediately after crossing into friendly airspace, he faced enemy fire. Determined to reach his base, Carr flew as low and fast as possible, a tactic that worked. However, by the time he arrived, his radio had stopped working.

Bruce Carr sticks the landing

Bickel had just one question for the pilot: “Carr, where in the hell have you been, and what have you been doing now?”

Bruce Carr’s service in Vietnam and Korea

Following World War II, Bruce Carr continued his service with the US Army Air Forces as it became the US Air Force. Initially, he was tasked with piloting the Lockheed F-80 Shooting Star as a member of the Acrojets, America’s inaugural jet-powered aerobatic demonstration team. Their base of operations was at Williams Air Force Base, Arizona.

During the Korean War, now-Maj. Carr flew an impressive 57 missions with the 336th Fighter-Interceptor Squadron, before assuming command of the squadron from January 1955 to August ’56.

Carr flew 286 combat missions in Vietnam

Subsequently promoted to colonel, Carr went on to serve in Vietnam, where he flew with the 31st Tactical Fighter Wing stationed at Tuy Hoa Air Base. Specializing in close air support missions, he accumulated a remarkable total of 286 combat missions flying the North American F-100 Super Sabre during his deployment.

More from us: The American Air Ace Shot Down By Friendly Fire During the Battle of the Bulge

New! Want to become a trivia master? Sign up for our War History Fact of the Day newsletter!

In 1973, Carr retired from the Air Force. For his service in three wars, he received an impressive number of medals, including the Distinguished Service Cross, the Legion of Merit, the Silver Star, 31 Air Medals and four Distinguished Flying Crosses.

In 1998, the skilled aviator passed away from prostate cancer and was buried in Arlington National Cemetery.