During World War II, numerous prisoners of war (POWs) were captured and held in custody. The Geneva Convention outlined the treatment they were entitled to receive. However, POWs detained in camps located within Allied-controlled Germany were deliberately categorized differently to get around these standards. These camps, referred to as the Rheinwiesenlager and formally designated Prisoner of War Temporary Enclosures (PWTE), are rarely discussed.

Allied success in Europe following the D-Day landings

Following the decisive success of the D-Day landings, the Allied forces progressed through occupied territories and penetrated into Germany. Despite pockets of resistance from some enemy troops, a substantial number surrendered, thereby placing the care of prisoners under the Allies’ purview.

Initially, custody of prisoners was shared between British and American forces, but by early 1945, the British refused to accept any more individuals into their existing camps. Consequently, the responsibility shifted entirely to the Americans, who faced the daunting task of accommodating the increasing influx of German POWs as the Allied advance continued.

To tackle this pressing issue, the US Army established the Rheinwiesenlager, a network of prison camps scattered across Allied-occupied Germany. While these camps started operations in April 1945, their significance soared after Germany’s surrender the next month, as they played a crucial role in preventing potential uprisings against the Allied presence.

Layout of the Rheinwiesenlager

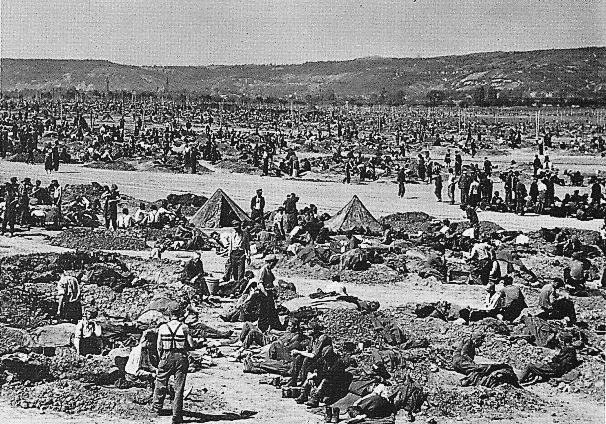

The Rheinwiesenlager was set up on territory within West Germany, under Allied jurisdiction. Positioned on agricultural terrain adjacent to railway tracks, these facilities were surrounded by enclosures of barbed wire. The land was subdivided into smaller sections, each designed to accommodate 5,000-10,000 people. However, numerous camps ended up overcrowded, hosting over 100,000 prisoners, with estimates suggesting a total population between one and 1.9 million.

The detainees in the Rheinwiesenlager were predominantly rank-and-file members of the Wehrmacht, while higher-ranking German officials, SS members, and other notable figures were relocated elsewhere.

Much of the camp’s internal organization fell to the prisoners themselves, who were responsible for tasks such as labor, medical attention, and meal preparation. Frequently, supervision of the compounds was entrusted to fellow inmates, incentivized with extra provisions to maintain order and ensure compliance within the confines of the wire boundaries.

While the compounds housed buildings primarily serving as kitchens, medical facilities, and administrative hubs, these were not allocated for prisoner living quarters. Instead, the majority of detainees were compelled to dig makeshift shelters in the earth.

Disarmed Enemy Forces (DEFs)

The poor conditions endured by these prisoners, shown even in their makeshift outdoor lodgings, underscored the harsh treatment given out by their captors. This mistreatment was largely allowed by their classification not as prisoners of war (POWs), but as Disarmed Enemy Forces (DEFs).

Before the opening of the Rheinwiesenlager, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower introduced this new classification, which effectively deprived DEFs of the protections afforded to POWs by the Geneva Convention on Prisoners of War (1929), on the grounds that they were members of state that no longer existed. This allowed for many forms of mistreatment

Under this classification, American authorities could “legally” prevent the Red Cross from visiting and stop the delivery of humanitarian aid. The Geneva Convention was specifically crafted to prevent the abuse of POWs, yet without its safeguards, DEFs were subjected to mistreatment with little to no repercussions for their captors.

These circumstances have led many to now view the inhumane actions of Eisenhower and those overseeing the Rheinwiesenlager as deliberate.

Rheinwiesenlager conditions

Overall, the conditions in the Rheinwiesenlager were horrific.

Historian Stephen Ambrose investigated many claims made about the camps, and concluded, “Men were beaten, denied water, forced to live in open camps without shelter, given inadequate food rations and inadequate medical care. Their mail was withheld. In some cases prisoners made a ‘soup’ of water and grass in order to deal with their hunger.”

Begging for more food wasn’t an option either, as those prisoners were often shot as “escapees,” should they have gotten near the barbed wire fences. Reports also claim locals would be shot if they tried to provide aid to the POWs.

Legacy of the Rheinwiesenlager

Given the living conditions of the Disarmed Enemy Forces, it’s no wonder the death toll was high. However, because they weren’t officially known as prisoners of war, few records were kept. Instead, many Germans would simply go missing from roll call, never to be seen again.

Due to the lack of records, death estimates vary, depending on who you ask. The official statistics from the US Army state that around 3,000 people died while in the Rheinwiesenlager. German estimates, however, provide a figure of 4,537.

James Bacque, the author of Other Losses: An Investigation Into the Mass Deaths of German Prisoners at the Hands of the French and Americans After World War II, alleges the number is between 100,000 and one million. However, his claims have been discredited by his peers.

More from us: The Battle of Cologne Saw a Legendary Standoff Between a Panther and a Pershing

Regardless of the overall death toll, the treatment of DEFs has been heavily criticized, despite it going largely unnoticed in more recent years. Many have pointed out that the Americans violated a host of international laws on the treatment of prisoners, even though they weren’t classified as POWs, particularly in their feeding – or lack thereof.