On August 6, 1945, the course of history was altered irrevocably as a Boeing B-29 Superfortress, piloted by Col. Paul Tibbets, dropped the first atomic bomb over Hiroshima. Three days later, another bomb was dropped, marking the conclusion of the Second World War. In the subsequent years, the US remained resolute in its commitment to testing the atomic weapons that played a pivotal role in securing victory, even at the potential cost of veterans.

Operation Crossroads

Named Operation Crossroads, the first round of additional US nuclear weapons testing took place in Bikini Atoll and the Marshall Islands in mid-1946. They were among many conducted in the area until the late 1950s and marked the first round of testing open to press and public observation, a significant departure from the previous top-secret nature of such endeavors.

As Vice Adm. William H.P. Blandy explained to the US Congress in the Cultural Resource Assessment, “The ultimate result of the tests, so far as the Navy is concerned, will be their translation into terms of United States sea power. Secondary purposes are to afford training for Army Air Forces personnel in the attack with the atomic bomb against ships and to determine the effect of the atomic bomb upon military installations and equipment.”

Under the supervision of Joint Army/Navy Task Force One, a fleet of 95 ships was assembled as targets for Fat Man-style bombs.

Castle Bravo

In the years that followed, the US continued to investigate nuclear weapons in the Marshall Islands with 67 different tests. Of all the experiments conducted, the worst by far was Castle Bravo. It was the largest nuclear detonation to date, as the bomb was over 1,000 times stronger than Little Boy, and was the first of a deliverable hydrogen bomb.

This was technically only one of three weapons tested during Operation Castle, a mission the US government considered to be extremely successful, as it proved there were different types of nuclear weapons that were just as effective. Castle Bravo was so notable because it had a detonation twice the size of what was expected.

It also led to a staggering amount of fallout, which hit nearby troops, as well as contaminated the local area.

Unintentional exposure

During Castle Bravo and Operation Crossroads, as with most of the other nuclear tests in the Marshall Islands, US soldiers and sailors were unintentionally exposed to high levels of radiation. In the instance of Castle Bravo, it was because the blast was so much larger than expected. The men were located on ships surrounding the mushroom cloud that were supposed to be a safe distance away, but ended up right in the middle of it.

For Crossroads, there was some management of radiation, as troops weren’t allowed to be exposed to more than the historically accepted safe amount of 0.1 roentgen per day. They were also kept away from areas that were believed to have higher levels of radiation.

Where exposure limits weren’t counted was among the troops who were responsible for cleaning up radiation-contaminated ships, something they did without safety equipment.

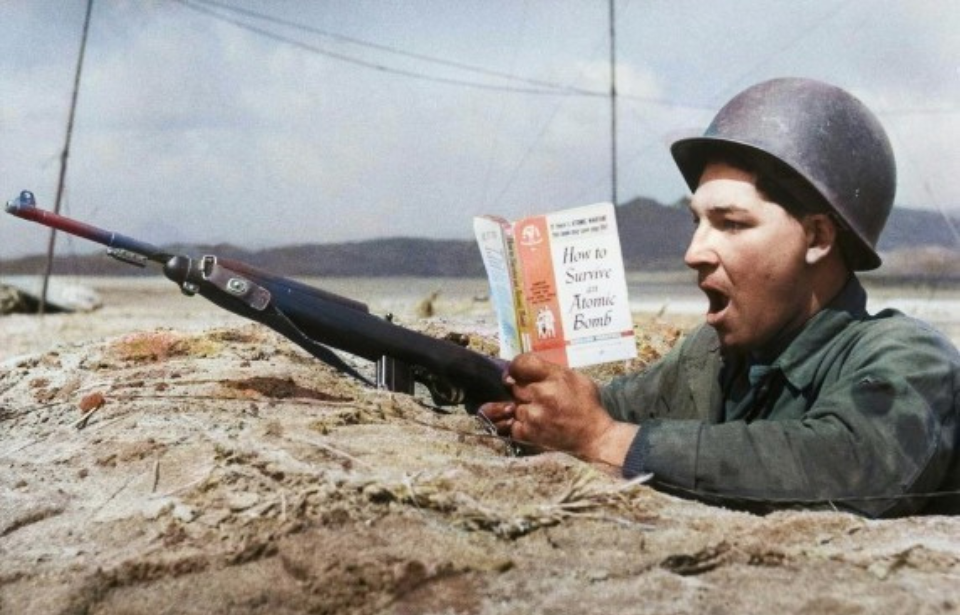

Nuclear test subjects

As was made clear by Vice Adm. William H.P. Blandy before the tests even began, there was more to it than just experimenting with weapons. The secondary goal was to test the physical and psychological effects of the atomic blasts on the servicemen. They were purposely placed on ships positioned only six to 11 miles from ground zero and forced to witness and experience the blasts for themselves. Supposedly, there were psychiatrists performing assessments on them before and after witnessing the explosion.

Many of the men recalled in later years what it was like being so close to a nuclear explosion, with one saying, “You could see the x-rays of your hands through your closed eyes,” and that the heat “was as if someone my size had caught fire and walked through me.” Another said, “If I was looking at you now, I would see all your bones. You would see all the blood vessels.”

Many of the men felt like they were being treated as guinea pigs.

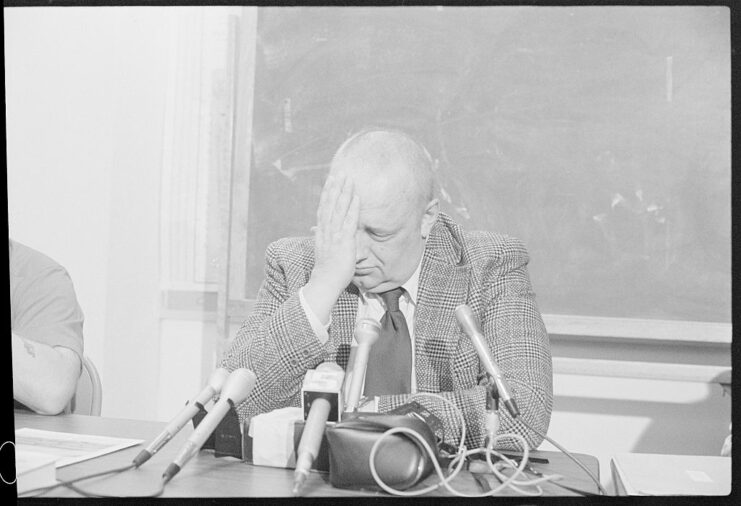

Investigating the veterans’ claims

Each of these servicemen were sworn to secrecy about what they experienced during nuclear testing. If they broke this oath, they could be fined $10,000 or sent to prison for over 10 years. This didn’t stop many from talking about what they’d experienced, especially when health problems – mainly cancers – began to arise.

In 1978, the National Association of Atomic Veterans was formed in an effort to help these men seek compensation from the government for their illnesses. Very slowly, there were more investigations into these claims. In some cases, like that of Harry Coppola, men were told they would get benefits if they kept their mouths shut. He refused, making his story extremely public.

John Smitherman, another veteran exposed to atomic energy, spoke out in the 1988 documentary Radio Bikini, which followed the effects of the nuclear tests in Bikini Atoll.

‘Atomic veterans’

After years of advocating for these men, a formal investigation was initiated by President Bill Clinton in 1994. It wasn’t until two years later that Congress repealed the Nuclear Radiation and Secrecy Agreements Act, allowing these veterans to legally talk about their experiences and seek benefits to cover medical treatment. Tragically, it was too late for many, who’d already died from radiation-induced illnesses.

It’s unclear when, but these service members were eventually given the name “atomic veterans.” According to a US Department of Veterans Affairs brochure, they were defined as those who were involved with aboveground nuclear testing between 1945 and ’62, were stationed in Hiroshima or Nagasaki before ’46, and/or were prisoners of war (POWs) in Hiroshima or Nagasaki.

More from us: With the Type 93 Torpedo, the Allies Didn’t Know What Hit Them… Literally

On July 15, 2021, US President Joe Biden issued an official proclamation declaring that, annually, July 16 would be National Atomic Veterans Day, in honor of the soldiers and sailors who bore the brunt of the testing at Bikini Atoll.