Canada wanted its air industry to be a global powerhouse

When the end of World War II was in sight, Canadian political and military leaders began looking to the post-war future. With the nation’s large number of aircraft factories still producing the Supermarine Spitfire and Avro Lancaster, they saw an opportunity.

With these factories, Canada would jump-start a major aircraft industry at the dawn of the Jet Age, designing and constructing aircraft in-house. However, officials didn’t plan on this being an ordinary industry. Instead, they aimed for it to be one the world simply couldn’t ignore. It was hoped that, with these designs, the country would establish itself as a major player in military and civil markets for years to come.

One of the first companies to spawn from this plan was Avro Canada, which quickly began work on a new jet-powered interceptor, the CF-100 Canuck. This aircraft experienced delays, but when it was ready proved to have a great design, allowing it to remain in service until 1981. However, as an interceptor, its performance was rather lackluster, especially against incoming threats.

Unfortunately, the CF-100 would be the only mass-produced Canadian-designed fighter in history. That being said, Avro Canada had already begun work on a successor before the aircraft had even entered service: the mythical Avro Arrow.

Designing the Avro Arrow

The Avro Arrow was to be Canada’s golden goose. However, as history would show, the nation had aimed too high.

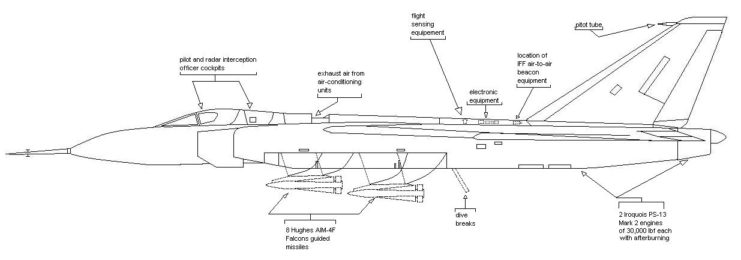

The requirements were given to Avro Canada in 1953: a two-man aircraft with two engines that could cruise at Mach 1.5 at an altitude of 70,000 feet. The company responded with the C-105, a 24-meter-long, twin-engine aircraft with an internal weapons bay capable of carrying a variety of guided missiles and free-falling bombs, and a distinct shoulder-mounted delta wing.

The proposal was so promising that, in July 1953, the project, renamed the CF-105, was given $27 million in funding. Just one month later, the Soviets detonated their first hydrogen bomb, after which they put the Myasishchev M-4 in the air. This led to the funding for the Avro Arrow being increased to $260 million, which would pay for the construction of five test aircraft, as well as 35 “Mark 2” Arrows with production engines and fire-control systems.

Testing the Avro Arrow

The design was thoroughly tested with scale models in a wind tunnel and extremely advanced computer simulations, resulting in a few changes, including the optimization of the nose and tail cones and the lowering of the wingtips. Titanium was used in some areas to help handle the extreme performance.

While the airframe was state-of-the-art, perhaps the most revolutionary aspect of the Avro Arrow was its flight-control system. Its wings and performance meant the aircraft had to use hydraulic actuators to move the control surfaces, which themselves were controlled by an early fly-by-wire system. This translated the pilot’s control column movements into signals that were sent to the hydraulics.

As the control column wasn’t physically connected to the surfaces, the pilot lost the “feel” of the aircraft and could also over-stress it by using too much force without knowing. Avro implemented a system that relayed the control surfaces’ movements back to the control column and artificially reproduced them with actuators, returning the feel of the aircraft to the pilot. The aircraft also used a high-tech Stability Augmentation System (SAS) that helped maintain the aircraft’s stability in all three axes of movement.

Avro unveiled the gleaming white Arrow to a crowd of 13,000 people in 1957, and the aircraft took its first flight on March 25, 1958. On the third test flight, it broke the sound barrier. By flight number seven, it passed 1,000 MPH. It showed brilliant flying characteristics during this time and almost reached Mach 2 during one high-speed flight.

The budget gets too big

All seemed to be going great for the Avro Arrow, which many hoped would lead Canada’s charge into the aerospace industry. Unfortunately, while it was shaping up to be a game-changer, the program’s ballooning budget, which totaled $1.1 billion, was becoming a game-breaker.

In mid-1957, the country’s Liberal government was voted out, in exchange for the Progressive Conservative Party, led by John Diefenbaker. For the new government, the virtually blank check given to the Avro Arrow was simply unacceptable.

At the same time, the United States was offering Canada national defense equipment at a much cheaper price, and the technology for intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) had advanced and people began expecting an attack to come from space, instead of heavy bombers. This was further proof that the Avro Arrow was not only too expensive, but also unnecessary.

The Avro Arrow was officially canceled

On February 20, 1959, on the day that became known as “Black Friday” in Canada, the Avro Arrow was officially canceled. Nearly 15,000 employees at Avro Canada and 15,000 more throughout its supply chain were instantly laid off. Shortly after, Avro Canada was ordered to destroy all plans, documents, blueprints, mock-ups and the completed aircraft themselves. However, some parts were smuggled by employees, and there’s even suspicions that a single Avro Arrow was saved and hidden away.

The cancellation essentially put an end to Avro Canada, which dissolved and was absorbed by Hawker Siddeley Canada. Canada would eventually buy 66 McDonnell CF-101 Voodoos to do the Avro Arrow’s work, albeit in a much less advanced way.

Want War History Online‘s content sent directly to your inbox? Sign up for our newsletter here!

The Avro Arrow has never been forgotten by Canadians, who are proud that their nation’s relatively small and inexperienced aerospace industry managed to create a truly groundbreaking aircraft.