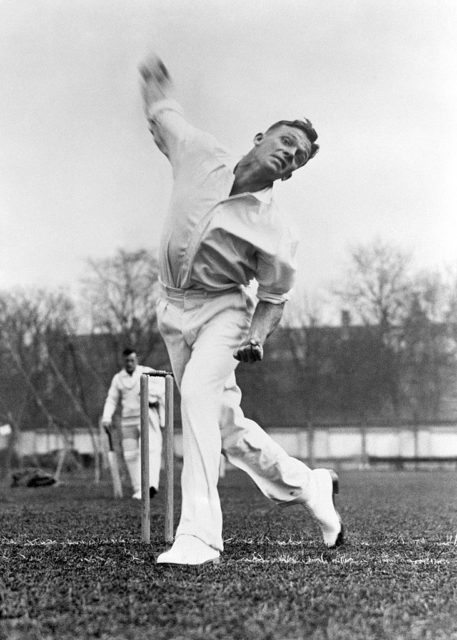

The majority of us lead lives that are fairly ordinary. There may be flurries of interest, even brief moments of heart-stopping excitement, but, most of the time, we just go quietly from day to day. There are some, however, who lead lives so packed with incident and achievement that their biographies read like a novel. One such person was Bob Crisp: international cricketer, mountaineer, journalist, writer, Civil Rights campaigner and war hero.

Bob Crisp becomes a professional cricket player

Bob Crisp was born in Calcutta, India on May 28, 1911. His family moved to Rhodesia (modern-day Zimbabwe), and he attended Prince Edward School in Salisbury, where it became clear he was a talented athlete. He represented the educational institution in swimming, boxing and athletics, but it was cricket where he excelled.

By the time Crisp left school, he was six feet, four inches tall and a ferociously fast bowler. He played his debut first-class cricket match in Bulawayo in 1929, and six years later became a member of South Africa’s national team.

During his cricket career, Crisp achieved several records, although not all were formally recorded. In the 1970s, a reporter with The Guardian was surprised to learn many cricketers still held him in awe as the first player to ever score 100 during a test tour. However, that’s not 100 runs – Crisp made love to 100 different women during his three-month tour of England in 1935.

During this period, the cricket player climbed Mount Kilimanjaro – twice. It seems he climbed the mountain alone and was on the way down when he met a friend, who was on their way up. Crisp agreed to climb the mountain again, but his friend broke their leg near the summit. Crisp carried him to the top, then back down to safety.

Commanding an M3 Stuart in the British Army

When the Second World War began, Bob Crisp enlisted in the British Army. After completing initial training, he was posted to the 3rd Royal Tank Regiment in Alexandria, Egypt. The regiment had lost all of its tanks and most of its personnel during the German invasion of France in the summer of 1940, and Lt. Crisp was one of many new member to join in early 1941.

Crisp spent most of his service as commander of an M3 Stuart. The tank was manufactured in the United States and provided to the British Army under the lend-lease policy. It featured a gasoline-powered radial engine that was originally designed for use in aircraft, but lacked range. The Stuart was a light tank, but was well-regarded by the British, being faster, more reliable and lighter than the other main tank of the time, the Crusader.

The Stuart had equivalent armor and armament to the Crusader, and its only real drawbacks were limited fuel capacity, a high profile necessitated by the location of its engine and a small, two-man turret. It wasn’t long before the 3rd Royal Tank Regiment discovered that the Stuart was also a match for the most common German-manned tank of the early war period: the Panzer III.

Bob Crisp takes on the Germans in Greece

In early March 1941, the 3rd Royal Tank Regiment was ordered to the port of Piraeus in Greece as part of the 1st Armored Brigade in Operation Lustre – an attempt to halt the German invasion of Greece and Yugoslavia. It was in the mountains of Greece that Bob Crisp encountered combat for the first time, and he embraced it with the same flamboyant enthusiasm with which he tackled most things in life.

Crisp is credited with destroying several German tanks during this brief campaign. When faced with a German Panzer IV, a much heavier tank than the Panzer III and virtually impervious to the main guns of British ones, the tank commander angrily stuck his head out of the turret and fired his revolver at it. When a British armored column was under attack by a Heinkel He-111 bomber, Crisp shot it down with the .30 caliber machine gun mounted on the cupola of his tank’s turret.

Unfortunately, the British campaign in Greece was a disaster. By the end of April, Crisp was forced to bail out of burning tanks three times, and the British forces were evacuated from Greece and pulled back to Egypt.

Bob Crisp was demoted a number of times

Bob Crisp was promoted to captain, being one of just twelve 3rd Royal Tank Regiment officers to make it back from Greece, but he didn’t keep the rank for long. He was demoted back to lieutenant following several incidents of insubordination and a tendency to spend more than he was paid.

Crisp was said to owe money to every bartender in Alexandria, something not seen as becoming of a British Army officer. He was demoted twice more during his career for similar reasons, something almost unique in the British Army.

Facing Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps

By the time that 3rd Royal Tank Regiment arrived back in Egypt, a new German force had entered the western desert. Gen. Erwin Rommel had been appointed to lead the Afrika Korps, a German expeditionary force sent to North Africa to support their Italian allies.

Rommel immediately led his men into eastern Cyrenaica, where they besieged the vital British port of Tobruk. In June 1941, the British counterattacked with Operation Battleaxe, a disastrous attempt to stop the German advance. They lost almost half of their tanks during the first day of fighting and, as usual, Bob Crisp was in the thick of the action. He fought continuously for 14 days in the failed effort to relieve Tobruk, surviving on little more than one hour’s sleep each night.

By June 17, the Germans were able to resume their advance, having destroyed almost 100 British tanks while losing just 12 of their own. The 3rd Royal Tank Regiment were pulled back to Cairo to rest and re-supply.

In November 1941, Crisp and his regiment were involved in Operation Crusader, yet another attempt to stop the inexorable advance of the Afrika Korps and relieve the siege of Tobruk. During bitter fighting, Crisp had two tanks shot out from under him. Then, near an airfield at Sidi Rezegh, he found himself alone in his Stuart when a column of 70 German vehicles appeared.

Crisp reacted immediately – and in characteristic fashion – by attacking the German force single-handedly. His tank careened through the enemy column, firing as it went. Taken by surprise and presumably assuming no-one would be foolish enough to attack alone and that there must, therefore, be a larger British force in the vicinity, the Germans withdrew.

The following day, Crisp was on foot when he spotted a German emplacement of three anti-tank guns, which threatened the British advance. He commandeered a passing Signal Corps Stuart, armed with only a machine gun, and attacked. Somehow, he destroyed the guns, captured their crews and freed a truckload of British prisoners of war (POWs).

Injuries take Bob Crisp out of service

As a result of these actions, Bob Crisp was recommended for the Victoria Cross, Britain’s highest award for bravery. However, Gen. Bernard Montgomery, the commander of British forces in North Africa, intervened. He wouldn’t countenance having such an insubordinate and profligate officer given this coveted award, and, instead, Crisp was awarded the Military Cross.

Before he could receive the medal, Crisp was wounded when yet another of his tanks was destroyed in the desert. He was hit in the head by shrapnel and badly burned. When King George VI, an avid cricket fan, presented the honor, he anxiously asked whether Crisp would still be able to play. He reassured the monarch, saying, “Fortunately Sire, I was only wounded in the head.”

However, Crisp’s wounds proved to be so serious that he, by this time a major and also the recipient of the Distinguished Service Order, was invalided out of the British Army soon after 3rd Royal Tank Regiment was involved in the invasion of Normandy.

Bob Crisp’s later life and death

Bob Crisp’s post-war life was anything but quiet. He worked as a journalist, but quit after disagreements with his editor. He wrote a book about his experiences in the war, Brazen Chariots, which the Los Angeles Times called “the finest narrative of tank warfare to come out of World War II.” He also started several businesses, all of which failed. By the 1960s, he was living on a Greek island, in a small goat hut which lacked running water or a toilet.

In 1971, at the age of 60, Crisp was diagnosed with terminal cancer. It was, doctors told him, inoperable, and there was nothing they could do for him. He bought a donkey and decided to spend what he assumed were his last few months walking around the island of Crete, bringing in a little money by selling the story of his walk to a newspaper.

During the journey, he was given a single dose of a new, experimental cancer drug, which was intended to be applied to the body. Misunderstanding, Crisp drank it, nothing it tasted so foul that he washed it down with a bottle of retsina. When he completed his walk several months later, doctors were astonished to find that the cancer had completely disappeared, although no one was able to explain why.

Crisp continued to work as a journalist, campaigning against apartheid in South Africa. He also co-founded Drum, the first magazine in South Africa geared toward Black readers. When the first ever cricket match was played between Black and White schoolboys in South Africa in 1989, he was there as a guest of honor.

Crisp also continued to be irresistibly appealing to women. A journalist who visited him in Greece noted that he had more than 20 girlfriends on the island. They ranged in age from their twenties to their fifties, while Crisp himself was 70.

More from us: Frederic Walker: The Most Successful Anti-Submarine Commander During the Battle of the Atlantic

Crisp never did get the hang of holding onto his money. When he died peacefully in his sleep in 1994, his only possessions were said to be a newspaper and a receipt for a £20 bet on an upcoming horse race. Nevertheless, he lived a life richer in experience and achievement than most of us can ever imagine.