Which aircraft equipped the ball turret?

The ball turret was initially developed by two separate companies, Emerson Electric and the Sperry Corporation. Development of the latter’s design was soon halted, with Sperry’s design being preferred.

The ventral ball turret was a hydraulically-operated, altazimuth mount addition to the two main aircraft that housed it: the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress and Consolidated B-24 Liberator. The implement was also equipped by the PB4Y-1 Liberators operated by the US Navy, as well as the B-24’s successor, the Consolidated B-32 Dominator.

Ball turret specs

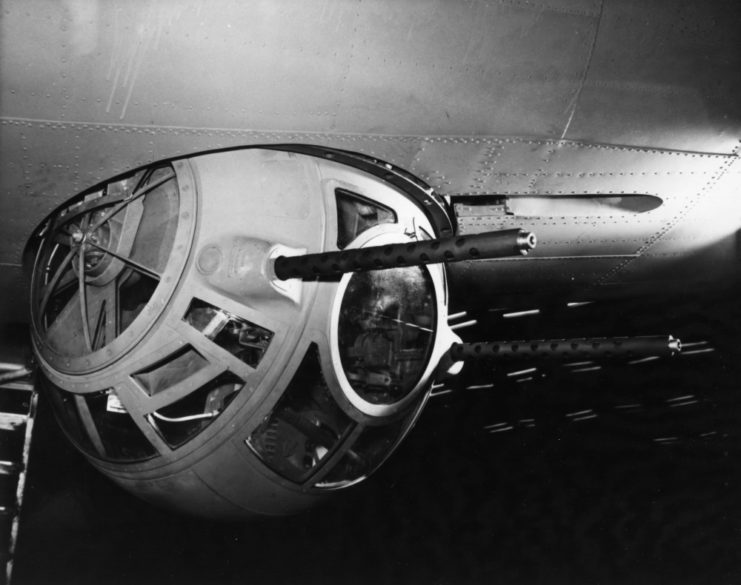

Despite its modest size, measuring only four feet across, the ball turret wielded considerable firepower. Its compact design served a purpose, minimizing drag during flight. Enclosed by armored plates, ball turret gunners were shielded during aerial combat, but their underneath position left them vulnerable in the event of the aircraft being shot down.

Equipped with two Browning AN/M2 .50-caliber machine guns, a Sperry optical gunsight and two ammunition cans carrying 250 rounds each, the turret boasted significant firepower. Its 360-degree rotation capability enabled the gunner to track and engage targets from any direction. The tight quarters of the ball turret meant manipulating the Browning handles was a major challenge, leading to the development of a pulley system for smoother operation.

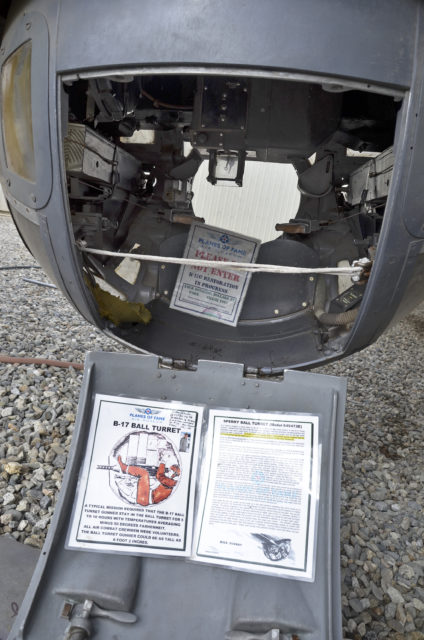

The design of ball turrets varied depending on the aircraft. The B-17, with its conventional landing gear, had a non-retractable mount, while the B-24, equipped with tricycle landing gear, required a vertically retractable mount to prevent the turret from hitting the ground during unstable takeoffs and landings.

Best airmen for the job

In 1941, the United States saw the establishment of numerous US Army Air Corps schools dedicated to training aerial gunners. At their peak, these institutions were producing an impressive 3,500 graduates per week, resulting in approximately 300,000 by the end of the Second World War.

Throughout the intensive six-week training program, recruits immersed themselves in subjects like range estimation, ballistics, aircraft identification and Morse code. The role demanded a high level of intensity, requiring trainees to make swift and often life-saving decisions. Before taking to the skies, aspiring gunners honed their shooting skills on the ground, progressing to live aircraft testing.

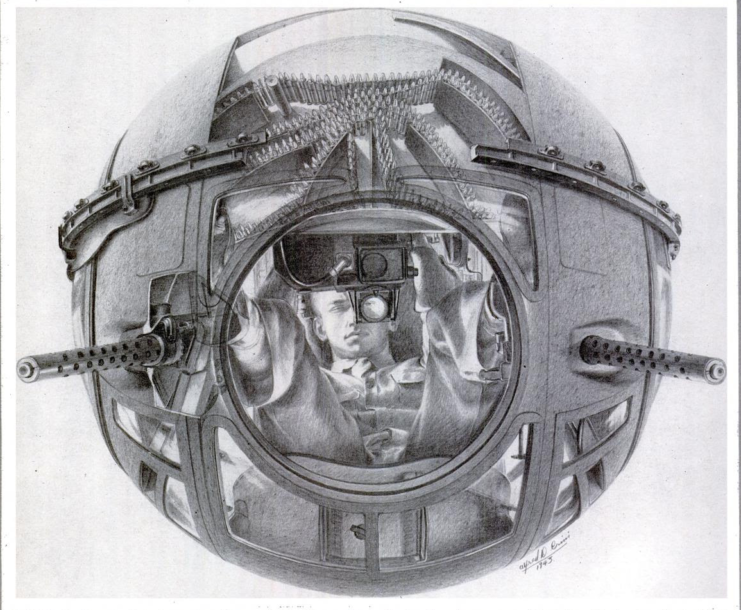

Due to the confined nature of the ball turret, the ideal candidates for this position were typically the smallest members of a crew; taller individuals would have struggled with the cramped and diminutive spaces. Adorned in flak jackets and electrically heated flight suits, these gunners stood ready to enter the uninsulated sphere, where a delayed reaction could make them vulnerable to enemy fire.

Taking on the enemy in a cramped ball turret

Entering the ball turret was no easy feat for gunners. They had to access it through a door located in the aircraft’s floor, aligning the ball so that its guns pointed toward the ground. Afterward, they positioned their feet on the heel rests inside and gradually lowered themselves into the confined space. To fit, they assumed a fetal-like posture, with knees drawn close to their bodies and their backs and heads against the rear wall.

This often had to be maintained for missions lasting up to 10 hours, which was undeniably uncomfortable.

The gunner held two joysticks, one in each hand – one for pivoting the turret ball and the other to operate the Browning machine guns’ firing mechanism. Foot pedals on the floor controlled the gunsight between their legs and managed an intercom system, which served as their sole means of communication with the rest of the crew.

Small windows afforded the gunner a view below the aircraft, but offered no visibility above.

Problem with parachutes

Due to its compact size, the ball turret couldn’t accommodate extra equipment. Consequently, the parachute, crucial in case the aircraft was shot down, had to be positioned outside of the turret door.

Regrettably, this location posed challenges, since the gunner had to open the turret door, enter the fuselage and secure themselves before any potential crash. To mitigate this risk, some opted for chest parachutes, but this wasn’t widespread.

Dangers of landing

Poet Randall Jarrell, who served in the US Army Air Forces, outlined the grim nature of being a ball turret gunner in his poem, The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner. He wrote, “When I died they washed me out of the turret with a hose.”

ERCO developed a second-generation ball turret

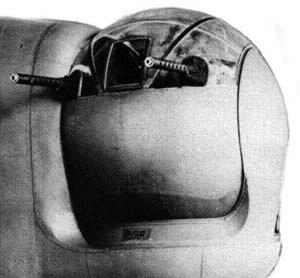

As the Second World War drew to a close, ERCO’s ball turret emerged as the favored apparatus for two bombers flown by the US Navy: the Consolidated PB4Y-1 Liberator and PB4Y-2 Privateer. Different from earlier models, this ball turret fulfilled dual roles during low-altitude assaults on enemy targets: it suppressed gun fire and performed strafing runs when it came to anti-submarine warfare, while also serving as a defensive measure against frontal assaults.

More from us: The Real-Life Marines Behind the Characters of ‘The Pacific’

Similar to earlier ball turrets, ERCO’s machine guns were operated by handles. They used the standard Navy Mk 9 reflector sight, which allowed for adequate aiming capabilities.