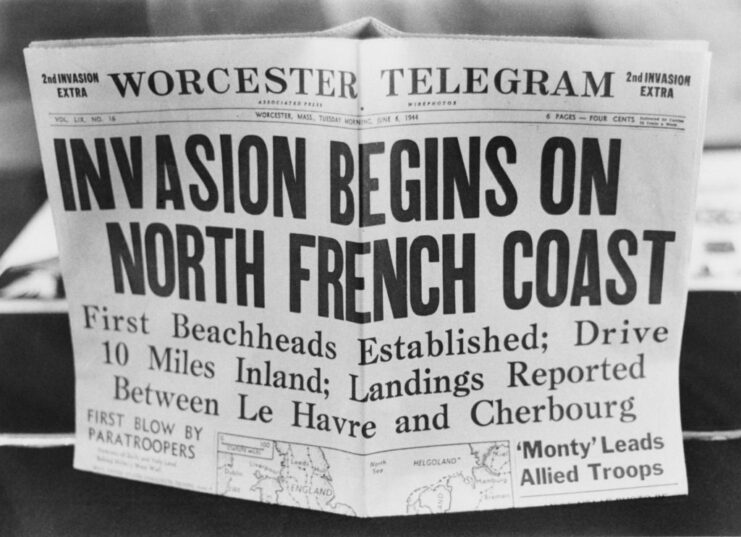

The D-Day invasion stands as a key moment in the fight against Germany during World War II. On June 6, 1944, Allied forces from various nations crossed the English Channel to land in Normandy, launching a decisive battle focused on freeing France and eventually all of Europe. This important day is remembered not only for its huge scale but also for its profound impact on the war’s trajectory.

Here are some essential details about the D-Day landings that you should know.

Operation Bodyguard came before Operation Overlord

Before the D-Day landings, the Allies implemented extensive strategies to ensure their success, including the deception of the Germans through Operation Bodyguard. This operation aimed to mislead German forces into thinking that the main Allied assault would take place at Pas-de-Calais rather than in northwestern France, thereby redirecting enemy resources away from the true D-Day landing sites.

A key element of Operation Bodyguard was Operation Copperhead, which involved using a doppelgänger of Bernard Montgomery to impersonate the well-known British officer across Allied territory. The purpose of this was to cast doubt on Montgomery’s involvement in the D-Day planning, as his purported travels suggested he could not be centrally involved. Furthermore, the lookalike helped spread false intelligence to reinforce the deception.

D-Day was initially slated to occur on June 5, 1944

June 6, 1944, stands out as an important moment in history, yet you might be surprised to learn that D-Day wasn’t originally planned for that day. The original schedule set the landings for June 5, but they were delayed by 24 hours after Irish postmistress Maureen Flavin Sweeney alerted the troops to the approaching bad weather.

The ultimate decision to postpone the landings was made by Supreme Allied Commander Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower. This choice not only ensured the operation’s success but also saved the lives of countless Allied soldiers.

Thousands of ships and landing craft were involved in D-Day

D-Day was centered around amphibious landings, which means the troops needed vessels to get across the English Channel.

It’s reported that nearly 7,000 ships and landing craft were used to ensure the success of the landings. Of that total, 80 percent were supplied by the British and 16.5 percent came from the United States.

What does the ‘D’ in D-Day stand for?

Let’s continue with a question many people have asked in the eight decades since the Normandy landings occurred: just what, exactly, does the “D” in D-Day stand for? As it turns out, the answer is pretty underwhelming.

The “D” is short for “Day,” meaning the entire name for D-Day is “Day-Day“. It doesn’t really roll off the tongue, does it?

A fatal live-fire rehearsal

A lot of preparation went into the D-Day landings, much of which involved training troops for what they could expect upon arriving in German-occupied France. Several coastal villages were taken over and numerous rehearsals were held.

One practice run was the fatal Exercise Tiger, which resulted in the deaths of over 700 Allied troops. Many of the casualties were killed during a live-fire exercise, while many others perished during what became known as the Battle of the Lyme, during which E-boats operated by the Kriegsmarine attacked Tank Landing Ships (LST) in the English Channel.

Nearly 160,000 Allied troops were involved in the D-Day landings

Given the major impact of the D-Day landings on the outcome of the Second World War, clear that the operation involved well over 100,000 Allied troops. Of the nearly 160,000 soldiers who took part, 83,000 were British and Canadian, while the remaining 73,000 were American. In comparison, the German forces numbered around 50,000 troops.

As Operation Overlord, also known as the Battle of Normandy, advanced, over two million Allied soldiers played an active role in the liberation of France.

What obstacles did the Allies face on the landing beaches?

The most notable defenses were Czech Hedgehogs, X- and L-shaped anti-tank barriers made from wood or metal. Additionally, there were other types of obstacles. Holzpfähle, wooden posts measuring between 13 and 16 feet tall, were scattered along beaches and fields, while disc-shaped teller mines were hidden throughout Normandy, set to detonate with 5.5 kg of TNT when triggered by soldiers or tanks.

No one wanted to wake the Führer…

As aforementioned, the Germans were anticipating an attack by the Allies, but that doesn’t mean they were willing to do anything to prevent the landings. What are we referring to, you ask? Waking the Führer from his slumber.

The Allies launched Operation Overlord early in the morning of June 6, 1944. When the call came to the Wolf’s Lair at 4:00 AM, the Führer was still fast asleep and no one wanted to wake him up; they were scared of what he’d do if disturbed. Without direct orders, German troops were left to wait on the sidelines while the Allies moved inland.

While the order eventually came, it was several hours delayed.

Sixteen soldiers received the Medal of Honor

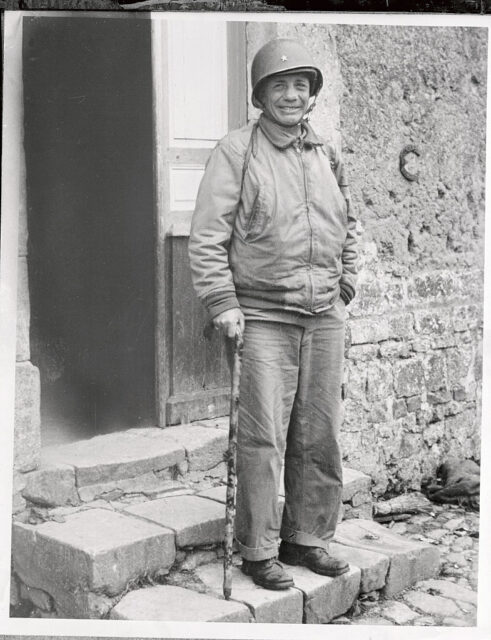

For their efforts during the D-Day landings and the wider Battle of Normandy, 16 American troops were awarded the Medal of Honor, nine of them posthumously. Of that total, four were directly related to action on June 6, 1944: Pvt. Carlton W. Barrett; First Lt. Jimmie W. Monteith, Jr.; T/5 John J. Pinder, Jr.; and Brig. Gen. Theodore Roosevelt, Jr.

If that last name sounds familiar, it’s because Roosevelt was the eldest son of US President Theodore Roosevelt. On D-Day, he directed the men who landed on Utah Beach, ultimately allowing the Allies to secure the beachhead.

Lt. Herbert Denham ‘Den’ Brotheridge

Have you ever wondered who the first Allied casualty of the D-Day landings was? According to reports, it was Lt. Herbert Denham “Den” Brotheridge, an officer in the British Army.

Serving with the 2nd Battalion, Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, he was killed while taking part in Operation Tonga, a mission undertaken by the British 6th Airborne Division to take control of and destroy the Merville Gun Battery. The site was approximately eight miles from Sword Beach.

While taking on German machine gunners, Brotheridge was hit in the back of the neck by enemy fire. While attempts were made to render medical aid, he perished.

Playing the bagpipes

Several notable individuals participated in the D-Day landings, but none were as unique as “Piper Bill” Millin, whose music led British Commandos from Sword Beach to Pegasus Bridge.

Millin played the bagpipes under Simon Fraser, 15th Lord Lovat, who’d been appointed the commander of the 1st Special Service Brigade (1st SSB). Under a hail of enemy and friendly fire, the former played his music, walking the entire length of Sword Beach three times, before moving toward the key bridge area.

How did he survive without a weapon, you ask? Well, according to a German soldier who spoke to Millin decades later, the enemy forces thought he was “off your head” – they didn’t want to waste their bullets on him!

Outnumbering the Luftwaffe 30:1

Approximately 11,000 Allied aircraft participated in the D-Day landings, a sizeable number, given the dwindling numbers of the Luftwaffe.

According to the BBC, the Allies outnumbered the Germans 30-to-one in the air. Given this, the latter failed to down any of the former’s aircraft in air-to-air combat.

How many casualties were suffered?

On June 6, 1944, alone, several thousand casualties were suffered by both sides. The Allies inflicted between 4,000 and 9,000 on the Germans, while they themselves experienced just over 12,000. According to the National WWII Museum, the breakdown for the Allies was:

- United States – 8,230

- United Kingdom – 2,700

- Canada – 1,074

Much of the footage was lost in the English Channel

Have you ever wondered why so little in the way of video footage exists of the D-Day landings? Well, the reason is it was accidentally dumped in the English Channel – true story.

Are you a fan of all things ships and submarines? If so, subscribe to our Daily Warships newsletter!

American film director John Ford was tasked with capturing footage of the landings on Omaha Beach, with the assistance of the US Coast Guard. The majority of the film reels were subsequently placed in a duffel bag bound for Britain. However, on the way, the bag was accidentally dropped into the English Channel by Maj. W.A. Ullman, a junior officer.