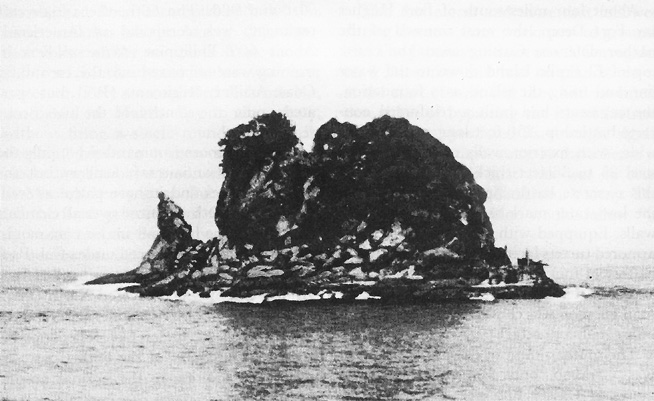

Fort Drum, or El Fraile, was a heavily-fortified island operated by the US in the Philippines for decades. The “concrete battleship” was constructed between 1909-14 and was built of reinforced concrete. Heavily fortified and practically impregnable, the fort saw a lot of action during the Second World War.

Battle of Manila Bay

On the evening of April 30, 1898, as part of the Spanish-American War, Commodore George Dewey led a US Navy squadron into Manila Bay. Spanish guns on El Fraile Island fired upon the USS McCulloch, whose crew returned fire. By illuminating the area with a flare, the crewmen also helped the USS Boston (1884), Raleigh (C-8) and Concord (PG-3) to fire back at the island. Despite attracting fire, the American ships were able to pass.

The following day, the Battle of Manila Bay was fought between American and Spanish naval forces, resulting in the American occupation of the bay. The 1899-1902 Philippine-American War and 1899-1913 Moro Rebellion would see the US occupy the whole of the Philippines.

Design of Fort Drum

The Board of Fortifications, under then-Secretary of War William Howard Taft, recommended the creation of fortified defenses in the bays and harbors acquired during the Spanish-American War. El Fraile was originally intended to become a mine control and casemate station. However, due to the region’s lack of defenses, it was decided it would, instead, be turned into a fort, resembling a concrete battleship.

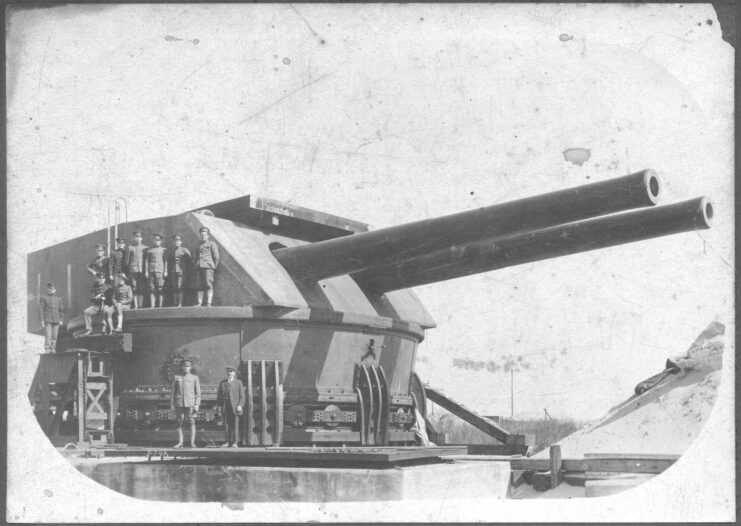

The island was leveled and a reinforced concrete structure built upon it, in addition to four guns in two turrets. The fort was named “Drum,” after Brig. Gen. Richard C. Drum. Originally, four 12-inch guns were to be mounted on twin armored turrets. However, these were changed to four 14-inch guns. In addition to the main guns, there were also four 6-inch guns and two 3-inch mobile anti-aircraft guns.

Fort Drum was heavily protected and virtually impregnable. The top deck was 20-feet thick, with its walls anywhere from 25-36 feet wide, depending on the location. All were made from steel-reinforced concrete.

Construction of Fort Drum

Construction on Fort Drum began in April 1909.

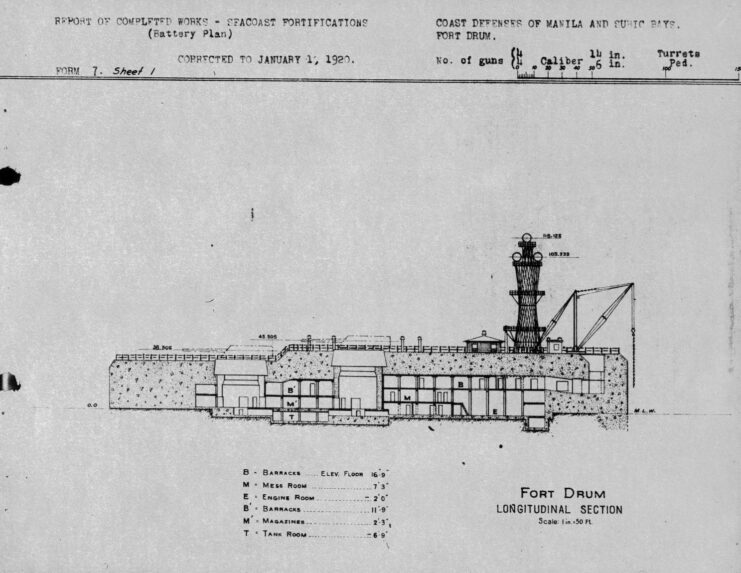

As aforementioned, the overall design resembled that of a battleship, 350 feet long and 140 feet wide. The guns were specially constructed and installed in 1916. On the upper deck, a 60-foot lattice-style fire control tower was installed. The living quarters for the 240 personnel manning the fort were located deep within.

The fort’s batteries were named after famous US servicemen. Two were named for Brig. Gen. William Louis Marshall and John Moulder Wilson, both American Civil War veterans and Medal of Honor recipients. The third was named after Chief of Artillery Benjamin K. Roberts, while the fourth was named for Artillery Officer Tully McCrea.

Philippines Campaign (1941-42)

Following the Japanese invasion of Luzon in late December 1941, Fort Drum came into range of the advancing enemy. Operating the fort was the 59th Coast Artillery Regiment (E Battery), stationed there since December 7. Prior to the start of the Second World War, wooden barracks had been constructed on the top deck, but these were dismantled, on account of the approaching Japanese.

On January 2, 1942, Fort Drum resisted Japanese air bombardments. Several days later, Fort Frank transferred a three-inch M1903 gun, in an effort to protect the stern of the concrete battleship. On January 13, Fort Drum became the first concrete emplacement to open fire on the enemy during the World War II, when a Japanese steamer attempted to survey the rear.

The installation came under heavy fire again in February 1942. This was so extensive that it destroyed the anti-aircraft battery, disabled one of the six-inch guns and saw large portions of the concrete structure chipped away. The fort’s main turrets remained operational, although they were ineffective against the Japanese.

Following the fall of Bataan, only Fort Drum and other such instalments remained under US control; almost all of the Philippines was occupied by the Japanese. The enemy, once again, attacked the fort on May 5 and suffered heavy casualties from its 14-inch guns. Despite the valiant effort, Corregidor fell the next day and Fort Drum was surrendered.

Before handing the fort over to the Japanese, the Americans disabled its guns, making them useless. During the fighting, only five injuries were suffered by those stationed on the concrete structure

Recapture of Fort Drum

The Japanese occupation of Fort Drum lasted until 1945.

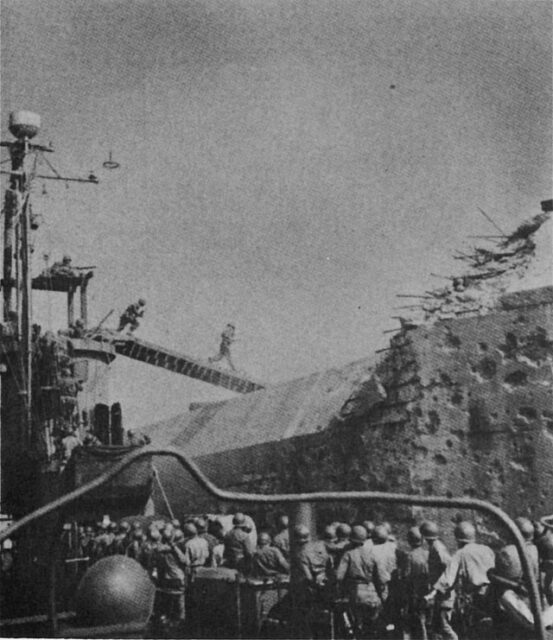

During the American offensive to retake Manila, the fort was the final Japanese possession in Manila Bay. On April 13, following heavy aerial and naval bombardments, American troops landed on the deck of the fort. Once there, they quickly retook control, confining the Japanese forces within.

Company F, 2nd Battalion, 151st Infantry Regiment, 38th Infantry Division, attached to the 113th Combat Engineer Battalion, attacked Fort Drum, having successfully taken Fort Hughes on Caballo Island. To take it, they used White phosphorus mortar rounds to ignite 2,500 US gallons, a mixture of two parts diesel and one part gasoline, which had been pumped in through a vent.

This technique was modified for Fort Drum. After the fuel mixture had been pumped into the structure, a timed fuse and 600 pounds of TNT were used to destroy the structure. The explosion was so large that a one-ton hatch was launched 300 feet into the air, and parts of the reinforced concrete were blown out.

The American forces had to wait five days to enter Fort Drum after the explosion, due to the fire and heat. The operation killed all of the Japanese soldiers within. The retaking of Fort Drum and others in Manila Bay ended all Japanese resistance in the region.

Fort Drum since the Second World War

At the conclusion of the Second World War, the US military abandoned Fort Drum. Having suffered significant damage during the conflict, the process of killing the Japanese soldiers who’d occupied the fort resulted in the gutting of the whole installation.

Are you a fan of all things ships and submarines? If so, subscribe to our Daily Warships newsletter!

Since the end of the war, looters have taken metal from Fort Drum, due to its high resale value. That being said, the concrete battleship in Manila Bay remains an enduring symbol of the American occupation of the Philippines.